First-come-first-served scheduling

AlgorithmCMPUT379Knowing how the OS works is crucial for efficient and secure programming, must like how knowledge of computer architecture is crucial for writing an efficient interpreter.

To study OS is to study the design of large software systems

E.g. we will learn the client-server model and how its equivalent is implemented in an operating system

An OS virtualizes a physical resource: it transforms a resource into a general and powerful virtual form of itself

The OS as a referee

The OS as an illusionist

The OS as a glue

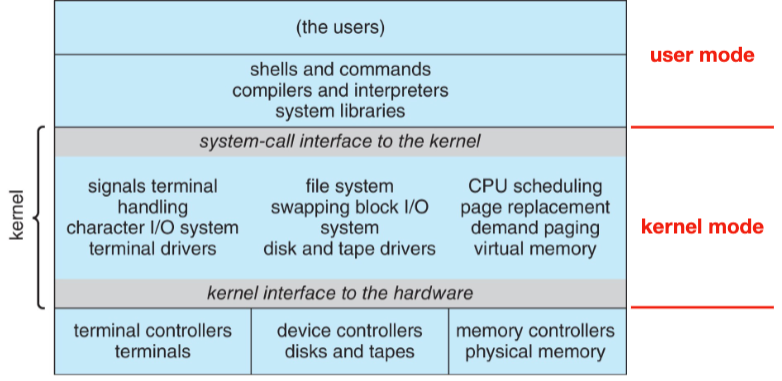

A core kernel that runs all the time in the kernel mode (supervisor mode/privileged mode)

System programs and daemons, which come with the operating system but are not part of the kernel

systemd is the system daemon in linux that starts all the other system daemonsMiddleware, which "connects" additional services to application developers, e.g. databases, multimedia, graphics

How does the OS make it easier to use and program a computer?

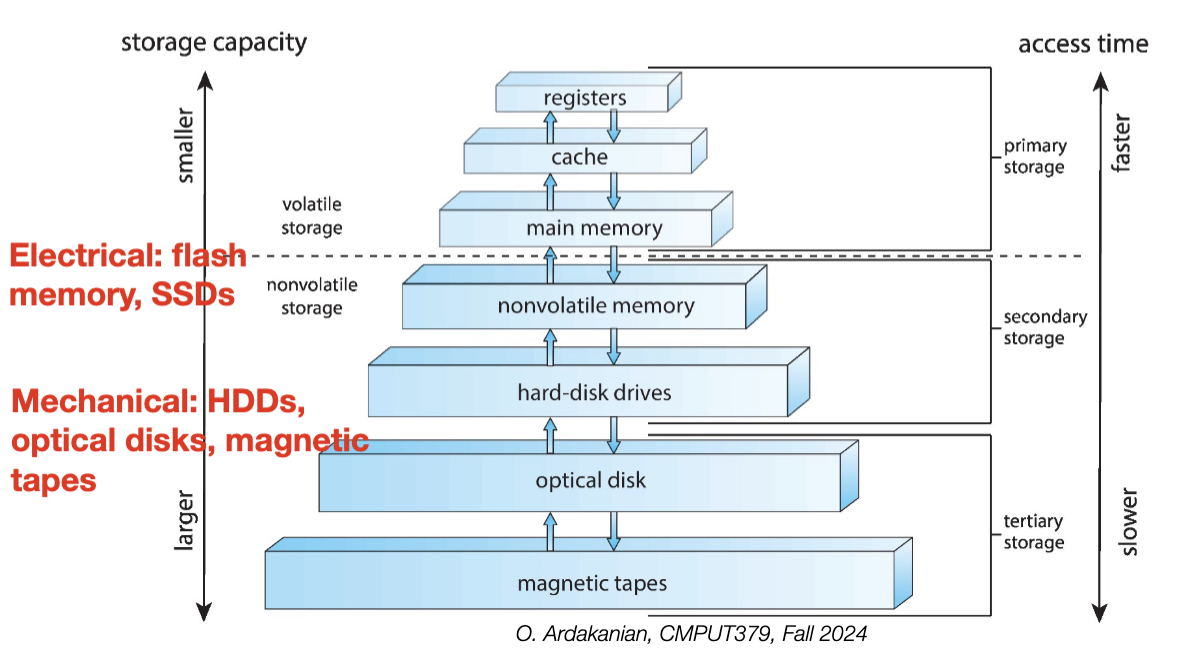

Recall that the CPU fetches and runs instructions one at a time, using the registers as its workspace. However, data doesn't just exist in the registers, but in memory and storage as well.

Because programs benefit from fast memory, it is economical to hierarchize the memory into several levels, each with a different zero-sum tradeoff between access cost (power) and speed. A clever compiler (or programmer) can make good guesses about which memory levels to use. Thus, having more memory options is generally more efficient.

A single-processor system contains one general-purpose processor with one processing core for user processes. In contract, a multiprocessor system contains multiple single-core CPUs, allowing multiple processes to run at the same time.

A multicore system has multiple cores residing on a single processor chip. Each core has its own L1 cache, but the L2 cache and below are shared between cores. Because less distance needs to be travelled, multicore systems are more efficient than their multi-chip counterparts.

An operating systems performs multiprogramming by keeping multiple processes in memory at the same time. The OS schedules the processes by picking one to run on the CPU, waiting until it terminates or has to wait, then picking another one, etc. This increases CPU utilization because a CPU core is less likely to be idle if it has multiple processes to choose from.

An interrupt is a signal sent by a device controller to the CPU's interrupt-request line(s) that informs the CPU that an event (e.g. an I/O request) has occurred.

There are actually two interrupt-request lines; the maskable one for device controllers, etc, and the non-maskable one for "urgent" interrupts like hardware faults. This way, if a critical process is running, the interrupt can be deferred until the process is complete by using the maskable line.

Interrupts have a priority level. The CPU will defer the handling of a low-level interrupt if a high-level interrupt is raised.

The CPU polls the interrupt-request line after each instruction. If an interrupt has occurred, the CPU stops what it was doing, catches the interrupt, and uses the in-memory interrupt vector to dispatch the appropriate interrupt-handler routine. The handler clears the interrupt by servicing the device.

If there are more interrupt handlers than addresses available in the interrupt vector, interrupt chaining can be used. Instead of pointing to a handler directly, an entry in the interrupt vector points to the head of a linked list of interrupt handler addresses. Each list entry is tried until one clears that handler.

An exception/trap is a software-generated interrupt that may be generated by an error (e.g. division by \(0\)) or a user request for an OS service (e.g. a system call or ecall).

Multitasking extends this idea to the process level by letting the CPU execute multiple processes at the same time; this is done by switching between them frequently. Choosing the next process to run requires CPU scheduling.

Lecture 3 slides Linking and Loading article

System calls are provided by the kernel to application programs

unistd.hThe following tasks require a (UNIX) system call to be executed. Consider how often your C programs do one of these things.

open(), close(), read(), write(), stat(), lseek(), link(), etc.chmod(), chown(), etc.getpid(), fork(), exec(), wait(), exit(), etc.The strace linux command can be used to trace which system calls are executed when an application is run.

Generally, system calls are called through a C library wrapper instead of directly. These functions are more convenient because they handle the steps around making the syscall, e.g. trapping to the kernel mode.

SYS_write via syscall() from syscalls.h calls the syscall directly, whereas calling write() from unistd.h calls it indirectlyThe POSIX API is a standard API across unix-based systems for system calls. This interface provides functions to interact with system calls that abstract away the low-level details of making the particular syscall on a particular system.

Thus, code calling this API is portable between (POSIX-compliant) systems because the implementation of a particular POSIX function is chosen for the system it runs on.

Here is where the philosophy of operating systems diverges from that of the languages they are written in; they do not give you enough rope to hang yourself with

An operating system has two (or more) operating modes that grant different levels of access to the hardware. Kernel mode grants the full privileges of hardware, whereas user mode does not. This design exists to protect the OS from user programs, and to protect user programs from each other.

The purpose of a system call is to allow a user program to run privileged instructions; access to these is mediated by the operating system. So, the underlying services of the OS can only be accessed through the "interface" (protection boundary) of an operating system in order to protect the hardware.

The computer's hardware has at least one status bit that indicates the current mode (i.e. user or kernel). Different hardware may have different modes → different bit configurations. So, the protection of privileged instructions happens at the hardware level.

Before context switching (switching processes), the OS loads a base/relocation register with the smallest legal physical memory address of the process and a limit register with the measure of memory allocated to the process. Then, in user mode, each reference (instruction and data address) is checked to ensure it falls between the base and the base+limit addresses.

It is possible that a process doesn't wait for I/O signals, and thus would continue running until termination (best case). To ensure the kernel gets regular control, a timer is set that interrupts the CPU at regular intervals (e.g. \(100\) microseconds).

Each timer interrupt, the CPU chooses a new process to execute.

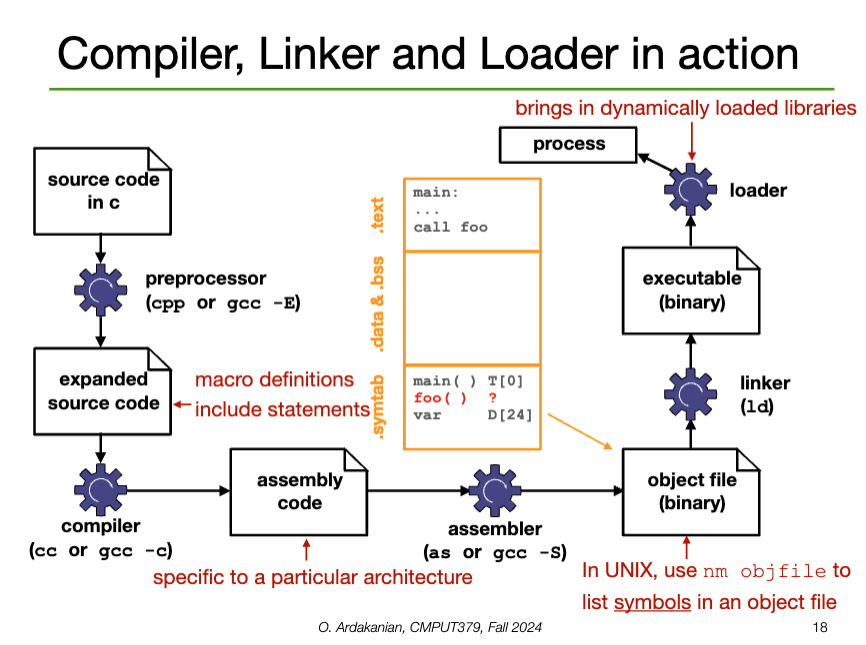

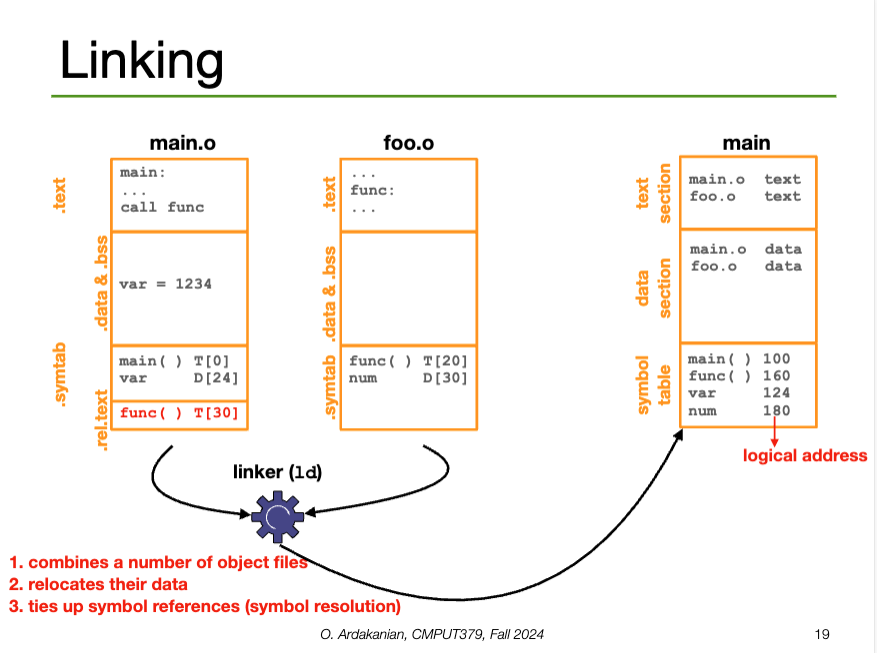

A compiler converts a source file (e.g. ASCII text) into an object file that corresponds directly to the source file

gcc -c main.c → main.ogcc-E), compiled, then assembled into the object file.A linker combines the object files and specific libraries into a single binary executable

gcc main main.o -lm → main (executable)A loader brings the executable file created by the linker into memory. Specifically, the loader adds the code and data from the executable to the process memory.

execve() syscallELF (Executable and Linkable Format) is the standard executable file format of UNIX systems.

The ELF Relocatable File contains the compiled code and a symbol table that contains metadata about functions and variables in the program; this is used to link the object file with other object files.

The ELF Executable File contains the address of the first instruction of the program; this can be loaded into memory

0x7F 0x45 0x4C 0x46 (the last \(3\) spell "ELF" in ASCII)| Name | Contents |

|---|---|

.text |

Machine code (instructions) The content of this can be viewed with objdump -drS objfile on UNIX systems |

.data |

Initialized global variables |

.bss |

(block storage start) uninitialized global variables empty in the object file (??) |

.rodata |

Read-only data, e.g. constant strings |

.symtab |

Symbol table |

.rel.text.rel.data |

Relocation information for functions and global variables that are referenced, but not defined in the file (i.e. external). The linker modifies this section by resolving external references |

make my own?

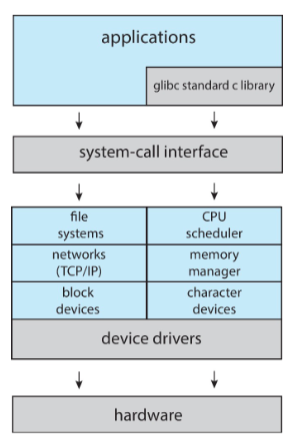

UNIX has a monolithic structure: everything in the kernel is compiled into a single static binary file that runs in a single address space. As a result, the communication with the kernel is fast and syscalls have little overhead.

LINUX is also monolithic, with a core kernel and additional dynamically loaded kernel modules for services like device drivers, file systems, etc.

Applications use glibc, the GNU version of the standard C library; this is where POSIX functionality is provided. glibc is the syscall interface to the kernel.

The marvel of software engineering that is the linux kernel is available online. Its directories are include (public headers), kernel, arch (hardware dependent code), fs (filesystems), mm (memory management), ipc (interprocess communication), drivers, usr (user-space code), lib (common libraries).

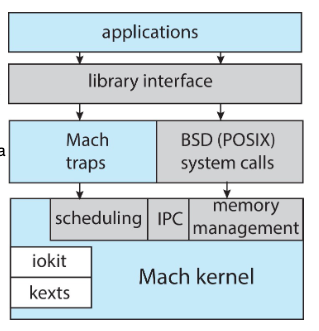

Darwin follows a layered structure with a microkernel, BSD (threads, command line, networking, file system), and user-level services (GUI). Layered structures have the following advantages and disadvantages:

The microkernel structure is characterized by a small kernel providing basically functionality (e.g. virtual memory, scheduling) and interprocess communication (e.g. message passing through ports). Other OS functionality is provided through user-level processes.

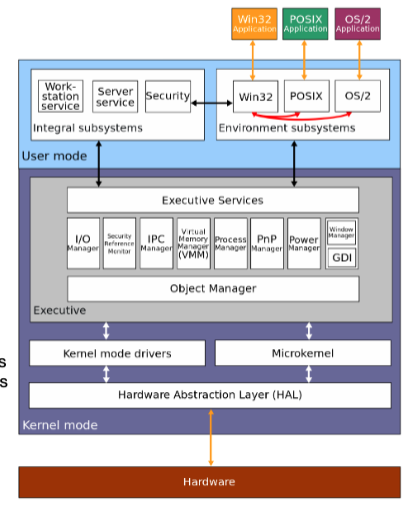

Windows NT is also layered, with the Windows executive (Ntoskrnl.exe) providing core functionality. The kernel(s) exist between the hardware abstraction layer and the executive services layer (where the Windows executive is). The kernel handles thread scheduling and interrupt handling.

The native Windows API is undocumented, so code requiring OS services (everything) runs on an environment subsystem with a documented API, like Win32, POSIX, os OS/2. WSL also fits into here I imagine.

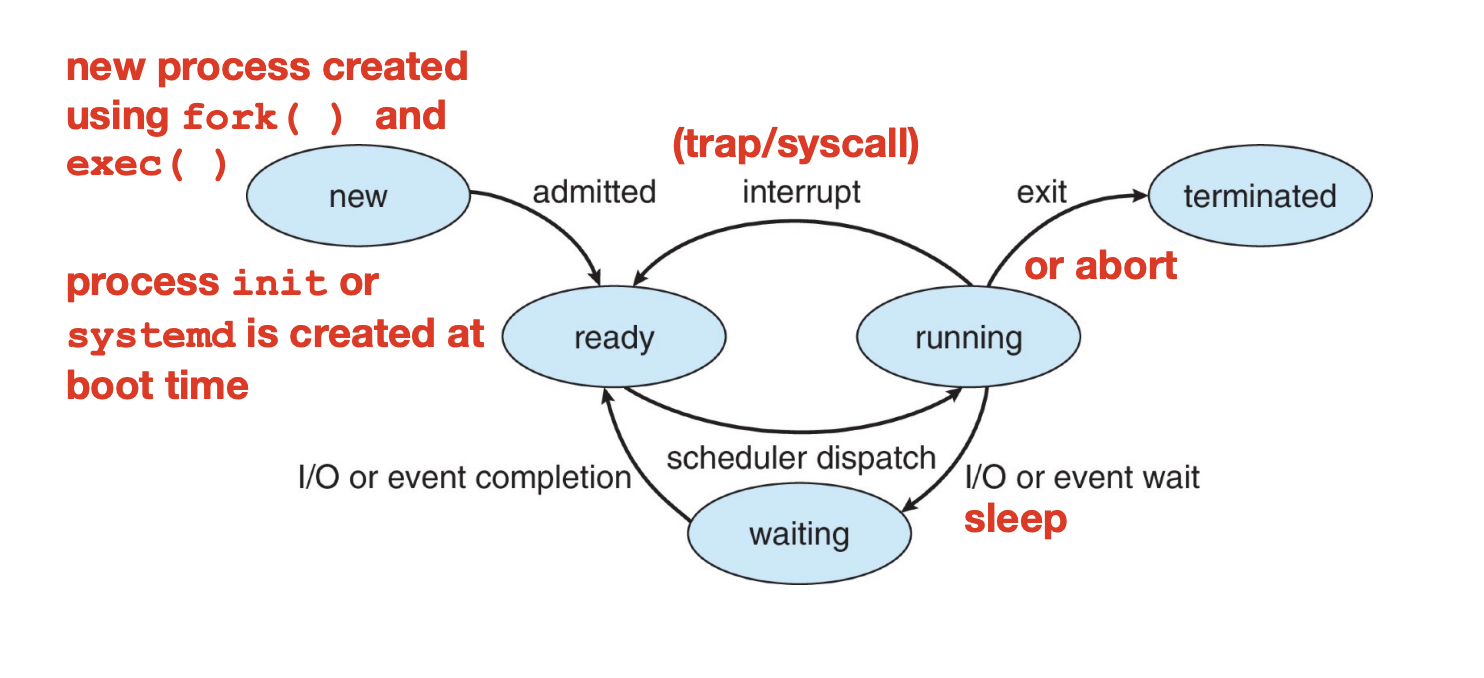

A process is a program being executed in an environment with restricted rights. The process has resources (e.g. CPU registers, memory to contain code, etc) and encapsulates one or more threads sharing process resources.

PID for "Process ID")Note that processes are not programs; different processes might run different instances of the same program, e.g. multiple instances of a web or file browser.

A process contains a

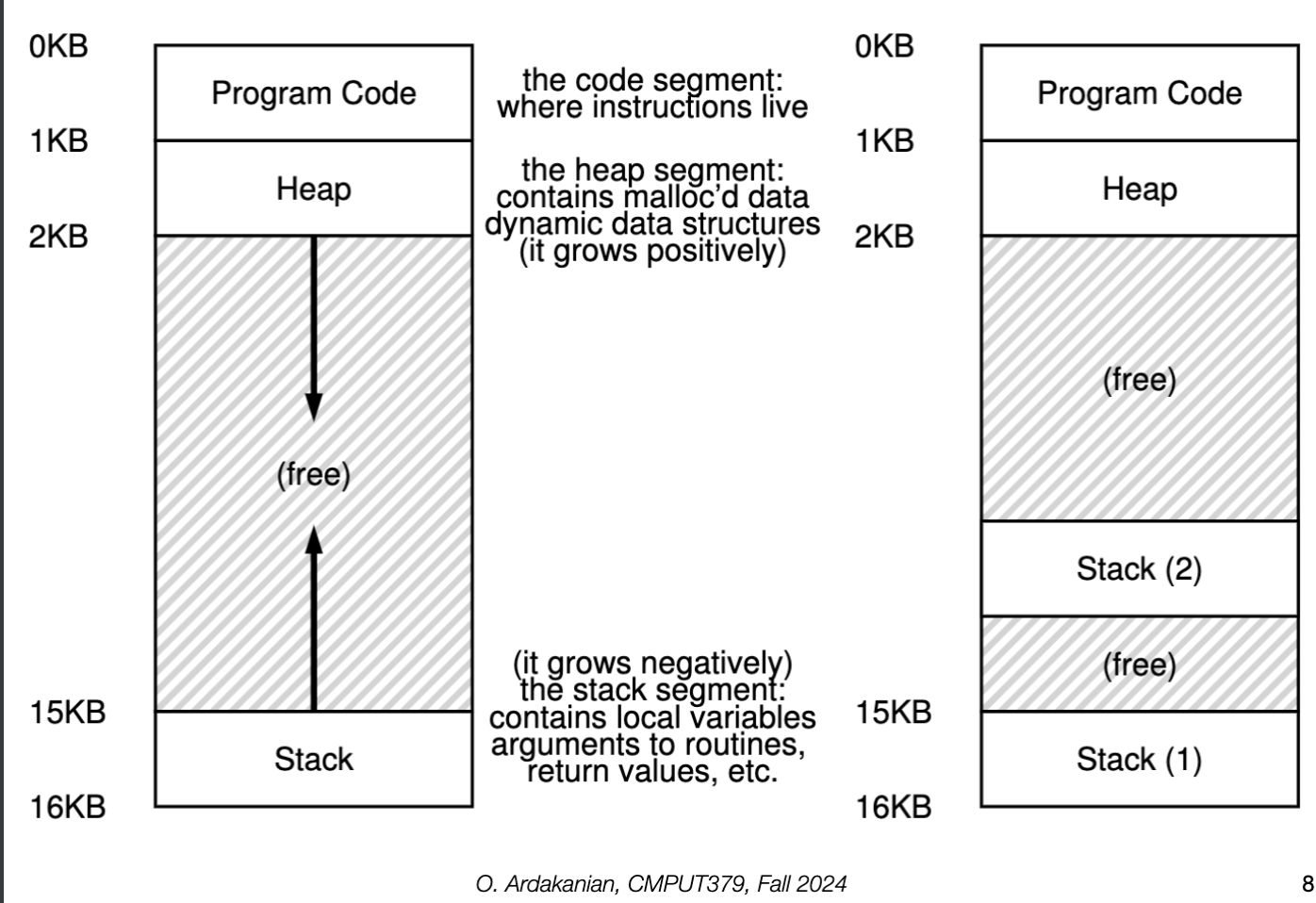

malloc() library function or the sbrk() system callSince both the stack and the heap are able to grow over a program's execution, they grow into the same unallocated space. Specifically, the stack grows downwards from the top of memory whereas the heap grows upwards, with respect to the memory addresses.

Each process has a distinct and isolated address space that defines which memory addresses it can access. No process can write to the memory of another process. The address space contains virtual addresses, which are translated to physical addresses by the hardware.

0x00000000; the addresses must be adjusted if the program is relocated.A thread is a sequential execution stream of instructions. A process may have multiple threads; these threads share the address space of the process as well as the heap, text, data, etc. However, each thread has its own registers, program counter, and stack.

The OS keeps track of the stat of each process' execution in a process control block (PCB). This is a kernel data structure in memory that represents the context (runtime information) about the process. This includes

running | ready | blocked/waiting | etc.PC, SP, HP (heap pointer), base and limit registers, page-table register, general-purpose registersIn Linux, the PCB is represented by the C structure task_struct, which is defined in <linux/sched.h>

Before a program is loaded into memory, the loader creates a PCB, address space, stack, and heap for the process. It also pushes argc and argv to the stack. Then, the registers and program counter are initialized. Finally, the data and program is loaded into memory.

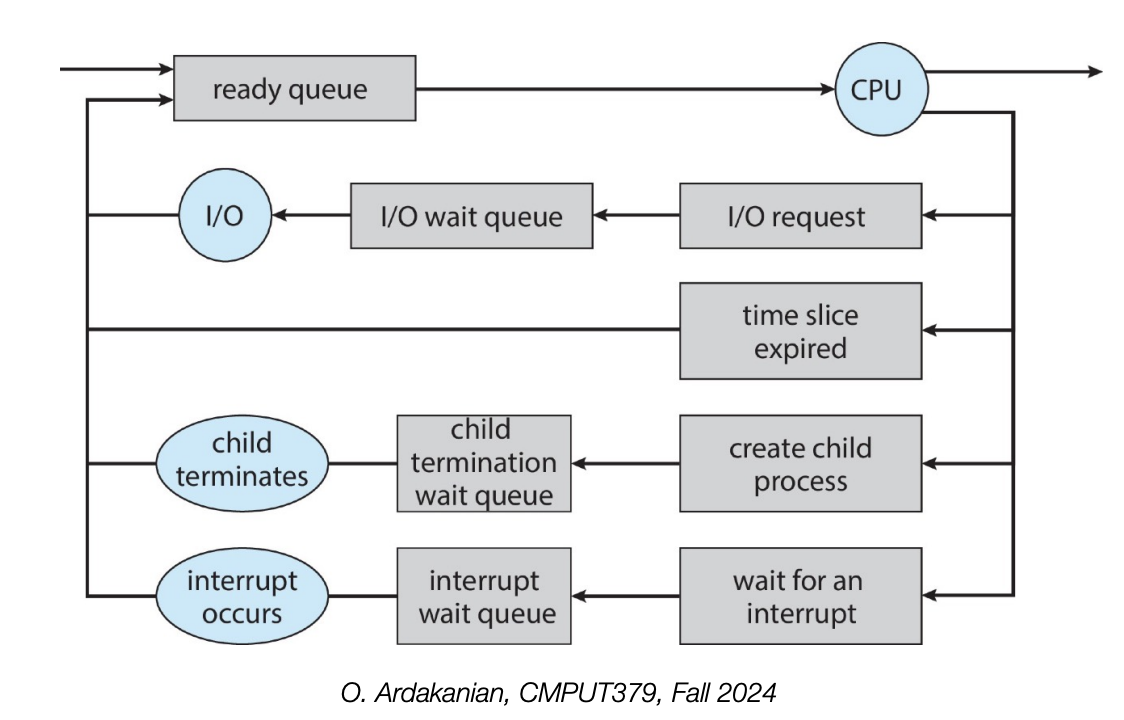

Although only one process can be running on a core at a given time, the OS is "juggling" many process, which may be in ready or waiting states. Active processes are placed in a queue to be dealt with. These include:

The queue may change due to a process action (e.g. termination or making a syscall), OS actions (scheduling), or external actions (hardware interrupts).

A process is a zombie process if it has terminated, but its parent hasn't read its exit status yet.

A process becomes an orphan process if its parent is terminated while the process is still running.

The scheduler maintains a doubly linked list of PCBs that are moved between the job queue, ready queue, and the device queues. It regularly selects a process from the ready queue to run; the algorithm defining this selection may be tuned to prefer fairness, minimum latency, guarantees.

Overall, the scheduler selects the process to run next, whereas the dispatcher actually executes the context switch.

Context switching is the act of stopping a process and starting another one; the context contains the values of the CPU registers, the process statement, and information about the memory.

Context switching is expensive because it requires loading the process' hardware registers (e.g. PC) from the PCB when the process starts and saving them to the PCB when the process ends.

How can we create, control, and terminate processes?

Go fork yourself

// returns the current PID

getpid()

// duplicates the current process (a new PID is assigned to the child process)

fork()

// loads a new binary file into memory without changing its PID

// this is the loader command from earlier

execve()

// waits until one of its child processes terminates

wait()

// waits until the specified child process terminates

waitpid()

// terminates a process

// note: _exit and exit are different things; this has CS 379 assignment implication

_exit()

// causes the calling process to sleep until a signal is delivered that either terminates the process or causes the invocation of a signal-catching function

pause()

// suspends execution of a process for at least the specified time (can be interrupted by a signal that triggers the invocation of a handler)

nanosleep()

// sends a signal (interrupt-like notification) to another process

kill()

// sets handlers for signals

sigaction() The fork (fork()) syscall creates a child process that inherits a copy of its parent's memory, file descriptors, CPU registers, etc. Both the parent and child process will execute after the fork instruction; either one might run first (no guarantee).

fork returns an integer \(n\) (technically of type pid_t):

systemd is the root process of entire "fork tree", with PID of 1.Presumably, the PID of the child is kept track of on the stack somewhere, lest a zombie process be created.

// includes

int main() {

// COMMON TO ALL PROCESSES

// fork 3 times

fork();

fork();

fork();

printf("hello\n");

// "hello" is printed 2^3 = 8 times

return 0;

}Note that the forked child processes can "see" everything, i.e. the code is running "multiple" times. This means we need to check if we're in the parent or child process when running code. It also means that anything before the fork is visible to both the parent and child processes; this lets us create shared structures like pipes, shared memory, etc.

So, DON'T FORK IN MULTITHREADED PROCESSES!

execve immediately afterwards.execveThe exec (execve()) system call allows a process to load a different program and start executing it at main. A number of arguments (argc) and an array of said arguments (argv) must be sent to the new program to be executed.

We usually call execve after calling fork. Note that this makes all the memory copied by fork useless immediately.

vfork if execve is called immediately; this doesn't copy all the memory over from the parent process. We won't need access to that memory if we call execve immediately, since it replaces the memory anywaywaitA parent process can execute concurrently with its children or wait until some or all of them terminate; this is achieved with the wait() command, which puts the parent to sleep until a result is returned.

exit() to indicate it is time to return to the sleeping parent processSIGCHLD signal to unblock the parent and return the child's value and PIDwait() returns immediately; if zombie children exist, one of their PIDs is returned and the zombie is killed_exitThe termination of a process is the final reclamation of its resources by the OS. All open files are closed and the process' memory is deallocated.

A process is usually terminated by using return in main, but it can be terminated explicitly by calling exit() (C library function) or _exit() (syscall). Note that exit() is called indirectly when main returns.

abort(), which generates the SIGABRT signal. Any functions registered with atexit() are not called, open files are not closed, etc. Not ideal!A process may terminate its own child with the kill() system call, which takes as parameters the child's PID and the signal to use, in this case SIGKILL

kill command uses the SIGTERM signal by defaultkillall, which kills by name instead of process IDA process becomes a zombie when it has terminated, but its parent has not yet called wait().

A process becomes an orphan if its parent terminates without invoking wait().

init (PID=\(1\)) process as its parent. We can check for this with if(getppid() == 1) in C.init repeatedly calls wait to allow the exit status or any reparented orphans to be collectedThe priority of a syscall can be adjusted with nice(); nice(incr) increases the nice value of the process by incr. A lower nice value has a higher scheduling priority; a process is "nice" by giving up some of its CPU share.

The ptrace system call lets a process intercept the system calls of another process. This lets it check arguments, set breakpoint, peep in on registers, etc

The sleep call puts the process on a timer queue by waiting for a certain number of milliseconds; this allows alarm functionality to be implemented.

In short, a shell is a process control system that lets programmers create and manage processes to do task. Logging into a (UNIX) machine starts a shell process

fork and exec are called implicitly, as a pairfork and exec#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

int main() {

//...

pid_t ppid = getpid(); // store parent’s pid

pid_t pid = fork(); // create a child

if(pid == 0) {

// child continues here

printf("Child pid: [%d]\n", getpid());

// ...

} else if (pid > 0) {

// parent continues here

printf("Parent pid: [%d] Child pid: [%d]\n", ppid, pid);

// ...

} else {

perror(“fork failed!”);

exit(1);

}

// ...

}We can run the ps command to check the process' IDs. The -el flag increases the information listed; the -u flag lets processes be filtered by the user that created them.

fork and wait#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

int main() {

// ...

pid_t ppid = getpid(); // store parent’s pid

pid_t pid = fork(); // create a child

if(pid == 0) { // child continues here

// ...

} else if (pid > 0) { // parent continues here

// ...

pid_t cpid = wait(&child_status);

} else {

perror(“fork failed!”);

}

// ...

}fork and exec#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

main() {

// ...

pid_t ppid = getpid(); // store parent’s pid

pid_t pid = fork(); // create a child

if(pid == 0){

// child continues here

// mark the end with a null pointer

status = execve("/bin/ls", arg0, arg1, ...);

/* exec doesn’t return on success!

so if we got here, it must have failed! */

perror(“exec failed!”);

} else if (pid > 0) {

// parent continues here ...

cpid = wait(&status); // pass NULL if not interested in exit status

if (WIFEXITED(status)) {

printf("child exit status was %d\n", WEXITSTATUS(status));

}

} else {

perror(“fork failed!”);

}

//...

}Welp, I'm on a watchlist now

#include <signal.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

main() {

// ...

int ppid = getpid(); // store parent’s pid

int pid = fork(); // create a child

if(pid == 0) { // child continues here

sleep(10); // child sleeps for 10 seconds

// ...

exit(0);

} else {

// parent continues here

// ...

printf( "Type any character to kill the child.\n" );

char answer[10];

gets(answer);

if (!kill(pid, SIGKILL)) {

printf(“Killed the child.\n”);

}

}

}"Kill" is the word associated with sending signals. For some reason.

Signals are software interrupts; they provide a way of handling asynchronous events by sending extremely short messages between processes (and are thus a form of PID). Each signal has an associated action.

Signals are defined as integer constants in the <signal.h> header; their textual representation always starts with "SIG", e.g. SIGKILL is \(9\).

kill -l can be used to list all the signals on some architecturesA signal is posted if the even that triggers it has occurred, delivered if the action associated with it is taken, pending if it has been posted but not delivered yet, and blocked if the target process does not want it delivered.

A signal can be generated by

ctrl-C → SIGINT (interrupt), ctrl-Z → SIGSTP (stop), ctrl-\ → SIGQUIT (quit)kill command or syscall, which is how we manually send a signal to a process.SIGURG, SIGPIPE, SIGALRMreliable-signalA process can send a signal to another process or a group of processes using the kill syscall. However, this can only happen if the user ID of the receiving process is the same as the one of the sending process (i.e. permission is required).

sigqueue functionraise function; raise(sig) is roughly equivalent to kill(getPID(), sig). This why we way processes "raise" exceptions; these are self-sent.A process can wait for a signal by calling pause; this puts the process to sleep until a signal is caught.

alarm function can be used to generate a signal for this purposeA process may have a signal disposition, which determines how it responds to signals.

SIG_DFL: let the default action happenSIG_IGN: ignore the signal (except for signals that can't be ignored, like SIGKILL and SIGSTOP)A signal handler is a function that takes a single integer as an argument and returns nothing, i.e. everything is accomplished through side-effects.

sighandler_t signal(int signum, sighandler_t handler);#include <stdio.h>, <unistd.h>, <signal.h>

int i; void quit(int code) {

fprintf(stderr, "\nInterrupt (code= %d, i= %d)\n", code, i);

}

int main (void) {

if(signal(SIGQUIT, quit) == SIG_ERR)

perror(“can′t catch SIGQUIT”);

// loop that wastes time in a measurable way

for (i= 0; i < 9e7; i++)

if (i % 10000 == 0) putc('.', stderr);

return(0);

}This behavior various across different UNIX versions though.

The action associated with a signal may be examined or modified using sigaction, which supersedes the signal function from earlier UNIX releases.

#include <stdlib.h>, <stdio.h>, <sys/types.h>, <unistd.h>, <signal.h>

void signal_callback_handler(int signum) {

printf("Caught the signal!\n");

// uncommenting the next line breaks the loop when signal received

// exit(1);

}

int main() {

struct sigaction sa;

sa.sa_flags = 0;

sigemptyset(&sa.sa_mask);

sa.sa_handler = signal_callback_handler;

sigaction(SIGINT, &sa, NULL); // we are not interested in the old disposition

// sigaction(SIGTSTP, &sa, NULL);

while (1) {}

}sigprocmask may be used to block signals in a signal set from getting delivered to a process.

The bit vector representing the signal set may be modified with sigemptyset(), sigfillset(), sigaddset(), sigdelset(), and sigismember()

When a process forks, the child inherits the parent's signal dispositions and signal mask; signal-handlers are also defined in the child because it has inherited its parents' memory.

When a process execs, the disposition of caught signals changes because its default action in the new program may be different; all other signal statuses are left alone and the signal mask is preserved.

Cooperating processes work with each other to accomplish a single task; this improves performance (e.g. increases parallelism) and program structure

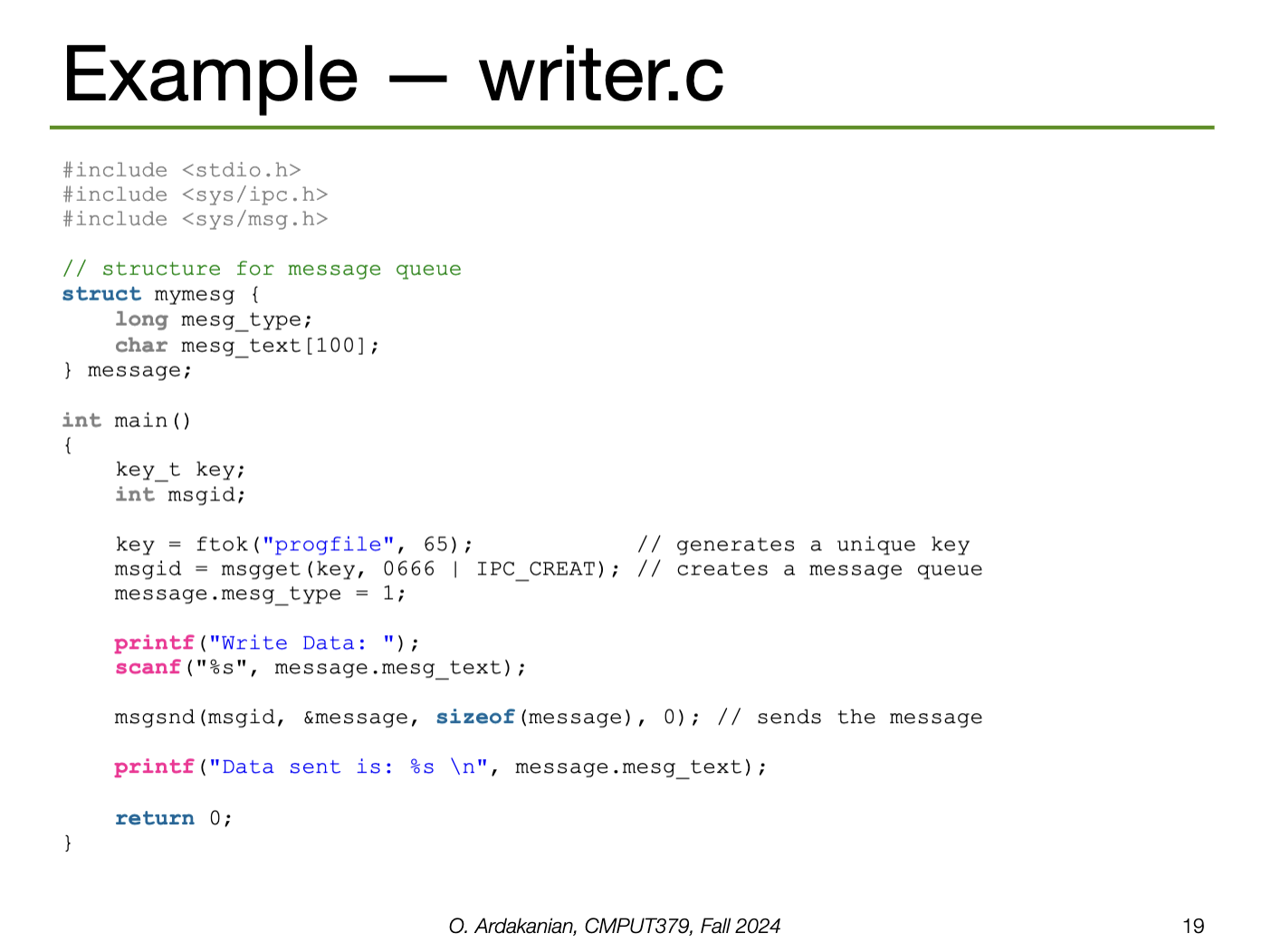

Information sharing (i.e. IPC) is likely required between cooperating processes; it is on the OS to make this happen. The two fundamental approaches to this are message passing using a message queue and shared memory.

Message passing requires kernel intervention through system calls. Sharing is clear and easy to track, but requires more overhead in the form of copying data and crossing domains.

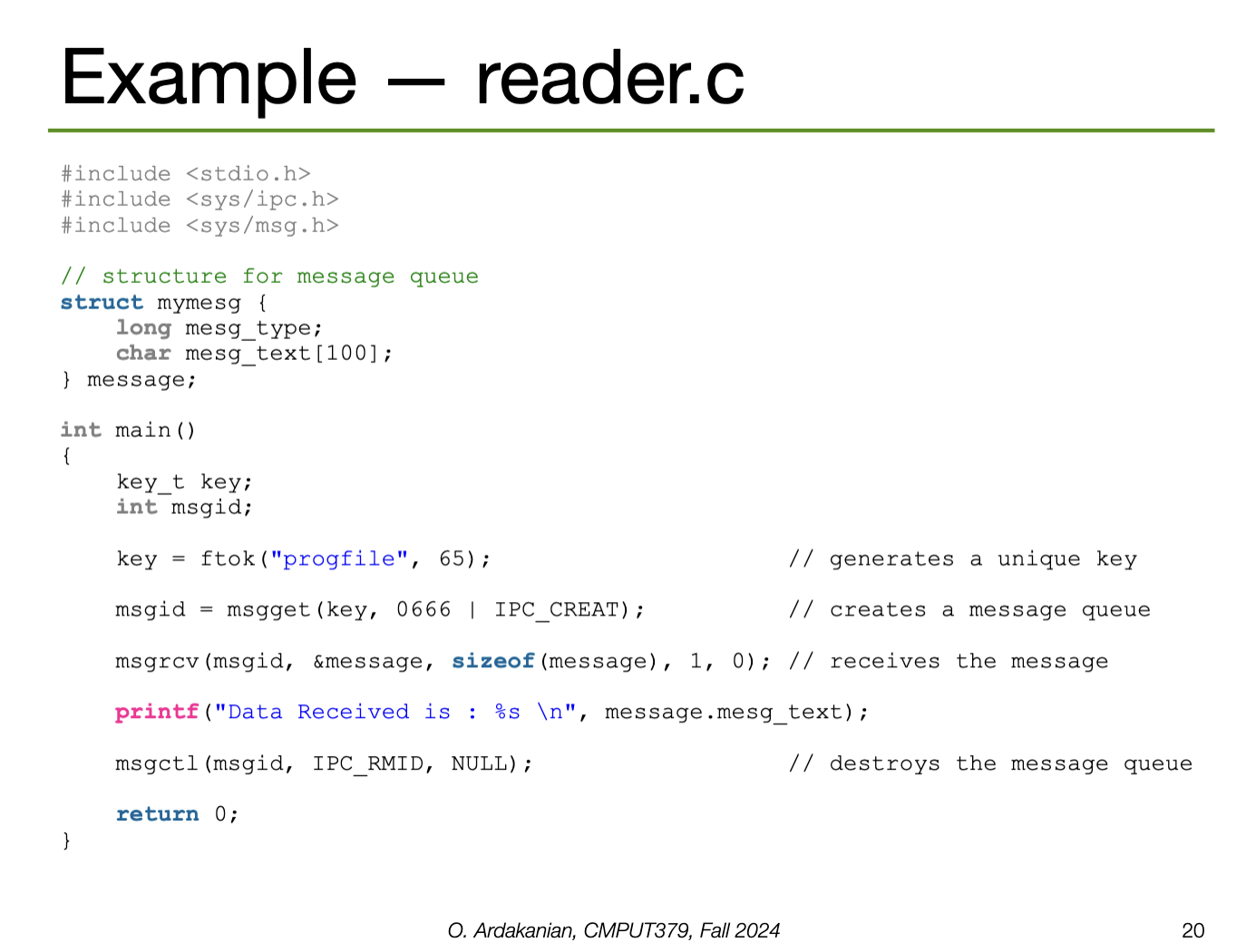

Implementation: a message queue (implemented as a linked list of messages) is stored in the kernel; a message queue identifier pointed to this list is shared with all cooperating processes.

send(consumer_pid, next_producer) and receive(producer_pid, next_consumer) syscalls.| Property | Options | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Direction | simplex | half-duplex | full-duplex | Which way the message travels (half-duplex: both ways, but one at a time) |

| Boundaries | datagram | byte stream | datagram has message boundaries, byte stream does not |

| Connection model | connection-oriented | connectionless | Connection-oriented: recipient is specified when the connection starts, so it doesn't need to be re-specified Connectionless: each send operation has a parameter that contains its recipient |

| Reliability | Can messages get reordered? corrupted? lost? |

Blocking: message passing may involve blocking operations, i.e. operations that force the sender and receiver to wait until the message has been received or is available, respectively.

Shared memory is achieved by establishing a mapping between a process' memory space to a named memory object, which is shared among processes. The processes that need access to the memory are forked after the memory is created so that they know the memory object's name.

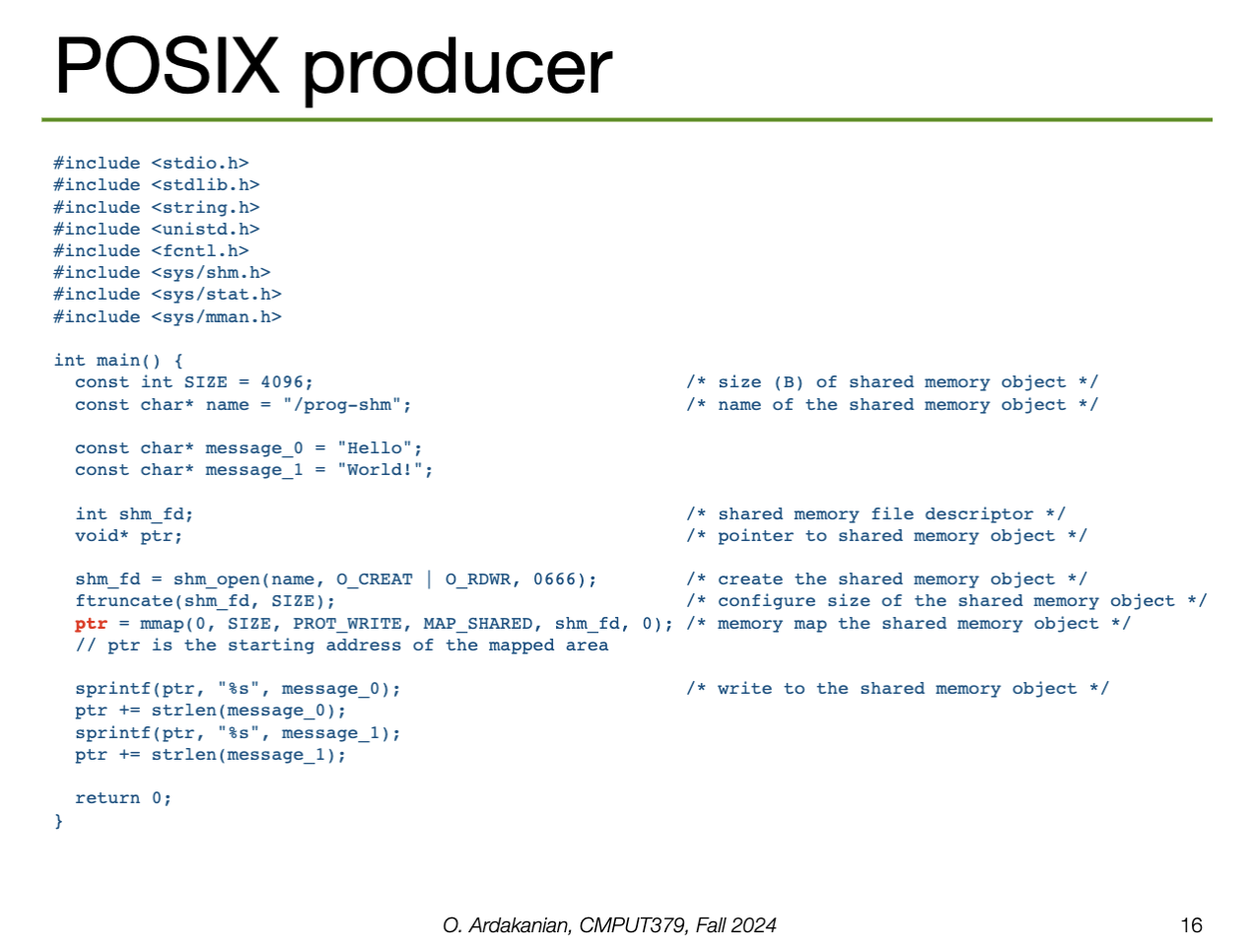

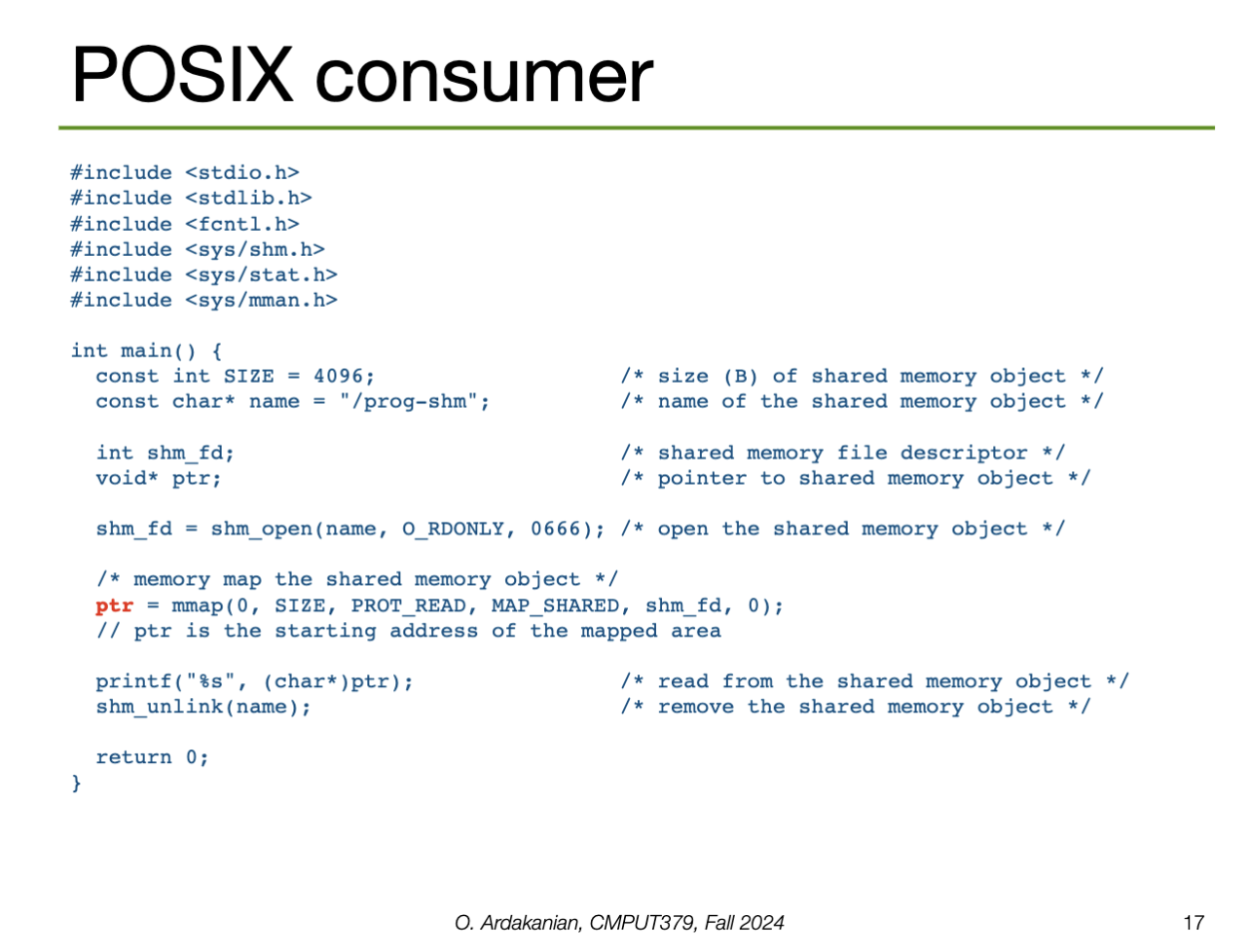

mmap() function to use the shared memoryPOSIX uses memory-mapped files; each region of the shared memory is associated with a file. So, shared memory objects are implemented with files. We interact with the SMO through the following syscalls:

shm_open(const char* name, int O_flag, mode_t mode) creates and opens a shared memory object; it returns a file descriptor that refers to the newly created object (since it is indeed a file)ftruncate(int file_desc, off_t length) lets us set the size of the shared memory objectshm_unlink(const char* name) removes the shared memory object by de-allocating (and destroying) the contents of the associated region of memoryFinally, mmap syscall establishes the memory-mapped file that contains this shared memory object. (we can remove this file with munmap). mmap takes parameters for the address of the shared memory section, the length (size) of the section, prot (?), flags, and an offset (?).

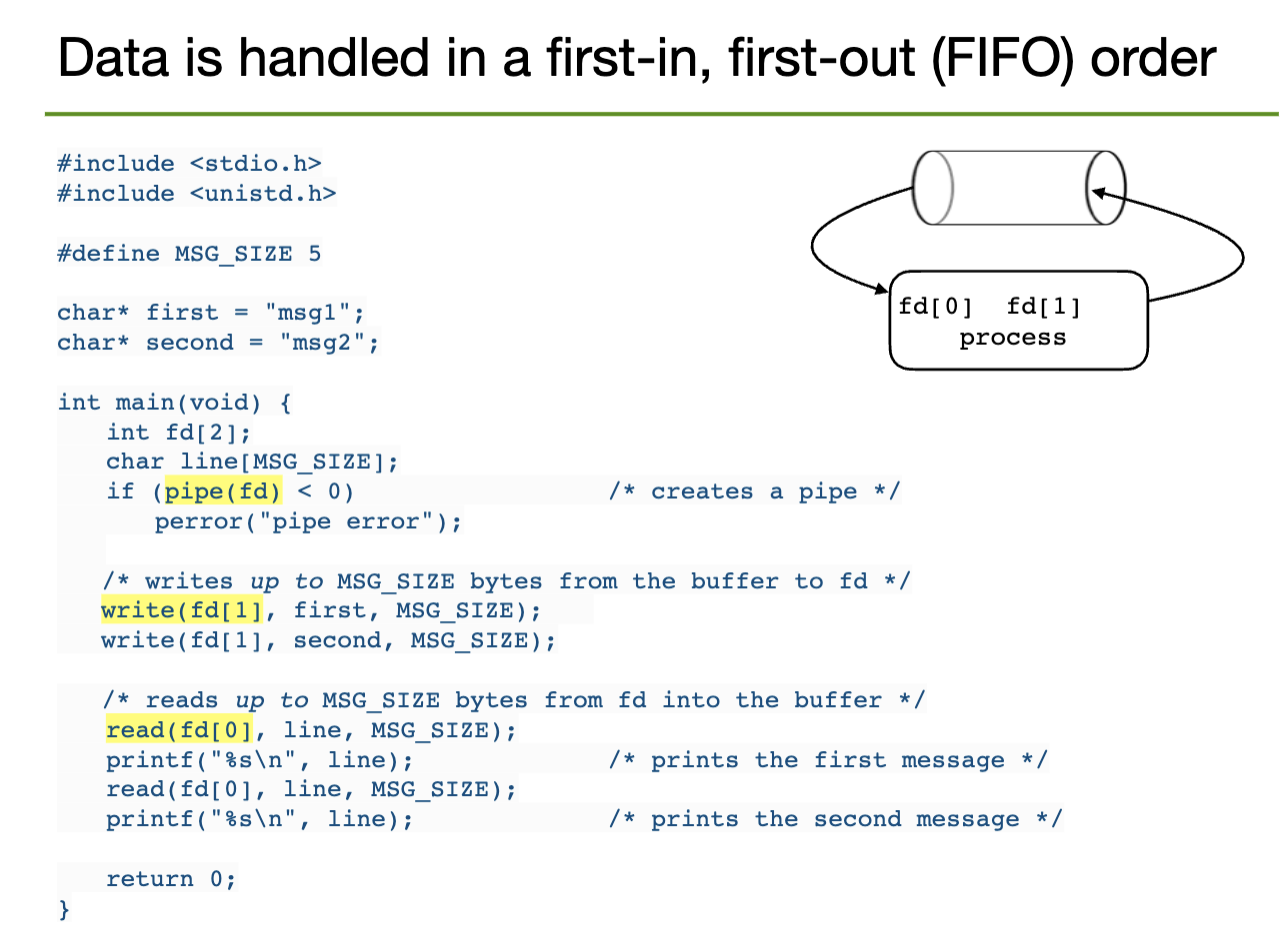

The producer-consumer problem (a.k.a the bounded buffer problem) any time we have a process (the producer) writing to a buffer and a different process (the consumer) reading from the same buffer. This pattern is common; a canonical example is in a shared pipe.

The producer-consumer problem requires the producer and consumer to communicate, i.e. inter-process communication is required. So, we can implement in terms of message passing or shared memory.

We defer the management of the message queue to the kernel, using send and receive as an interface to interact with the queue. Each process needs to be able to name (identify) the other processes to communicate.

while(true) loops here because are are always waiting for a new update from the buffer; this is a common pattern in systems that wait for interruptions and/or have blocking processes, e.g. user input (e.g. dragonshell) or waiting for the message queueint main() {

//...

int(fork() != 0) {

producer();

} else {

consumer();

}

}

int producer() {

//...

while(true) {

//...

next_p = /* produced item */;

send(C_pid, next_p);

//...

}

}

int consumer() {

//...

while(true) {

//...

receive(P_pid, &nextc);

// consume nextc

//...

}

}this code doesn't quite make sense to me

We use the mmap system call to create shared memory. We store the buffer in this shared memory and manipulate it directly. As such, we need to keep track of some variables and constants

N (constant) is the size of the buffer. In this example, we use a circular buffer, i.e. where we loop back around to the start when we reach the end (typically implemented with a modulus operator)in points to the next free location and out points to the next full location (i.e. where we should read from)

int main() {

//...

mmap(/*...*/, in, out, PROT_WRITE, PROT_SHARED, /*...*/);

in, out = 0;

if(fork() != 0) producer(); else consumer();

}

int producer() {

//...

while(true) {

//... (produce the item however)

nextp = /* produced item */;

// wait until we have something to put in the queue

while((in + 1) % N == out) {}

// if we're here, (in + 1) % N != out, so we write to the buffer

buffer[in] = nextp;

in = (in + 1) % N;

}

}

int consumer() {

//...

while(true) {

//...

// wait here until there is something to read from the buffer

while(in == out) {}

// read from buffer

nextc = buffer[out];

// update out; we implement a circular buffer with the modulus operator

out = (out + 1) % n

// consume the next item however

}

}To create the producer, we use shm_open to create the shared memory file descriptor, then call ftruncate to establish the size of the shared memory. Then, we use mmap to create the shared memory object and get a pointer to it. Finally, we use sprintf to write write to the shared memory; we increment the pointer to make sure we're writing to the right place.

We do all the exact same setup as the consumer: shm_open and mmap (among others) with the same name. However, instead of writing to the shared memory, we read from the memory instead by setting it as the "source" for printf. Finally, we call shm_unlink to remove the shared memory object when we're done.

Note: the notes also have examples of this in System V; I'm not sure these are as directly relevant so I didn't include them. But, they are useful for comparison of system design, so I've made a note that these are indeed in the slides.

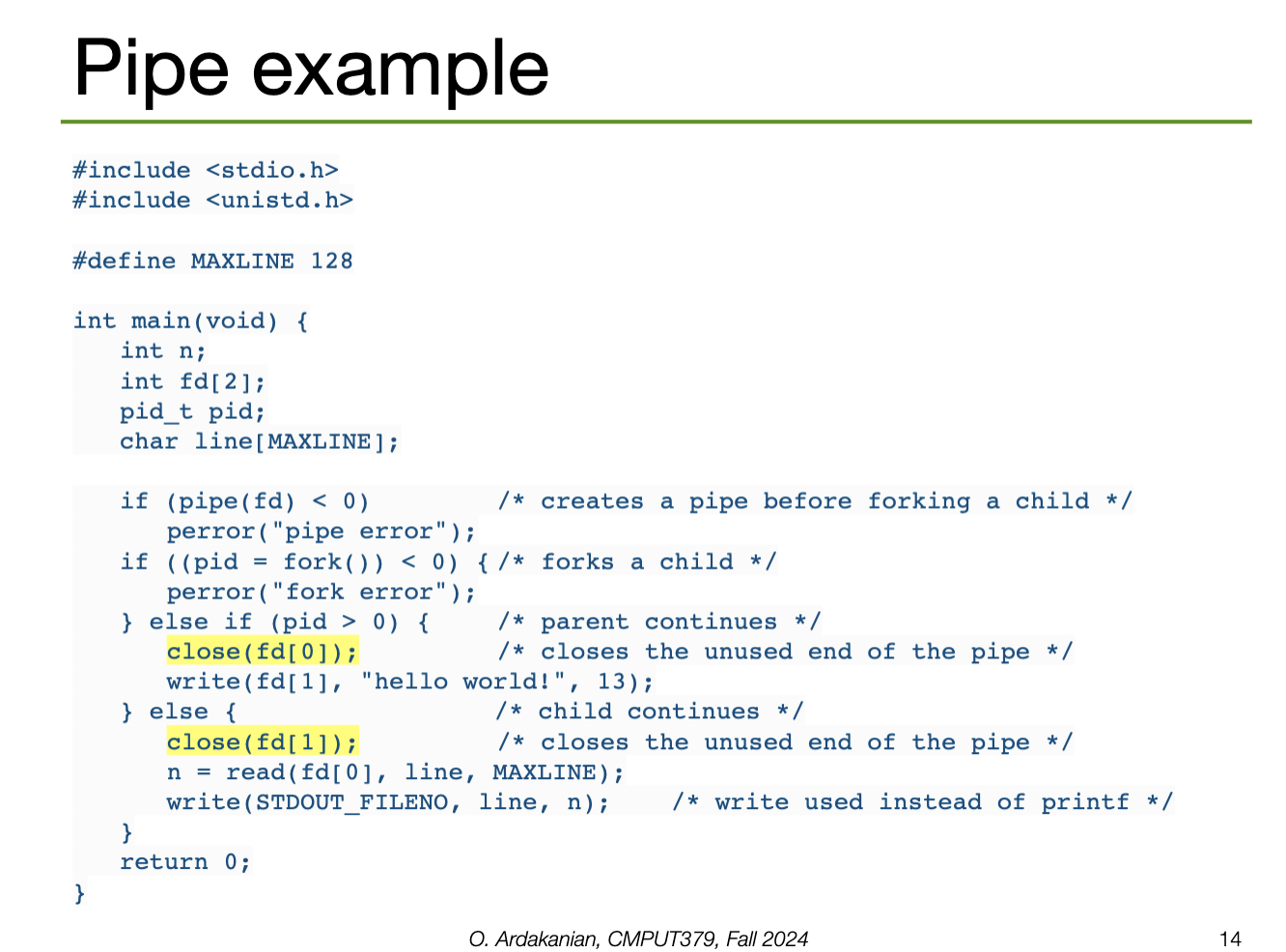

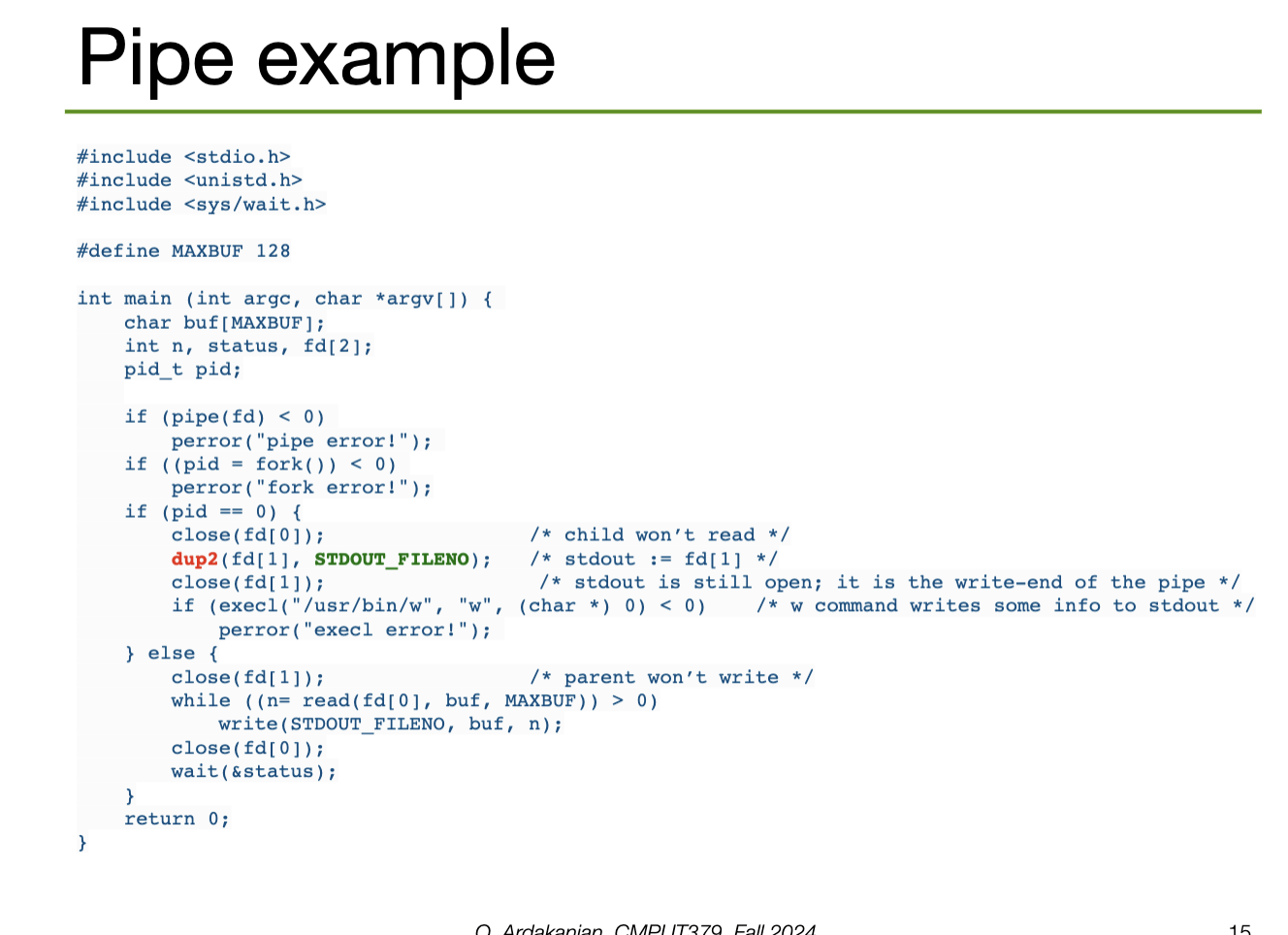

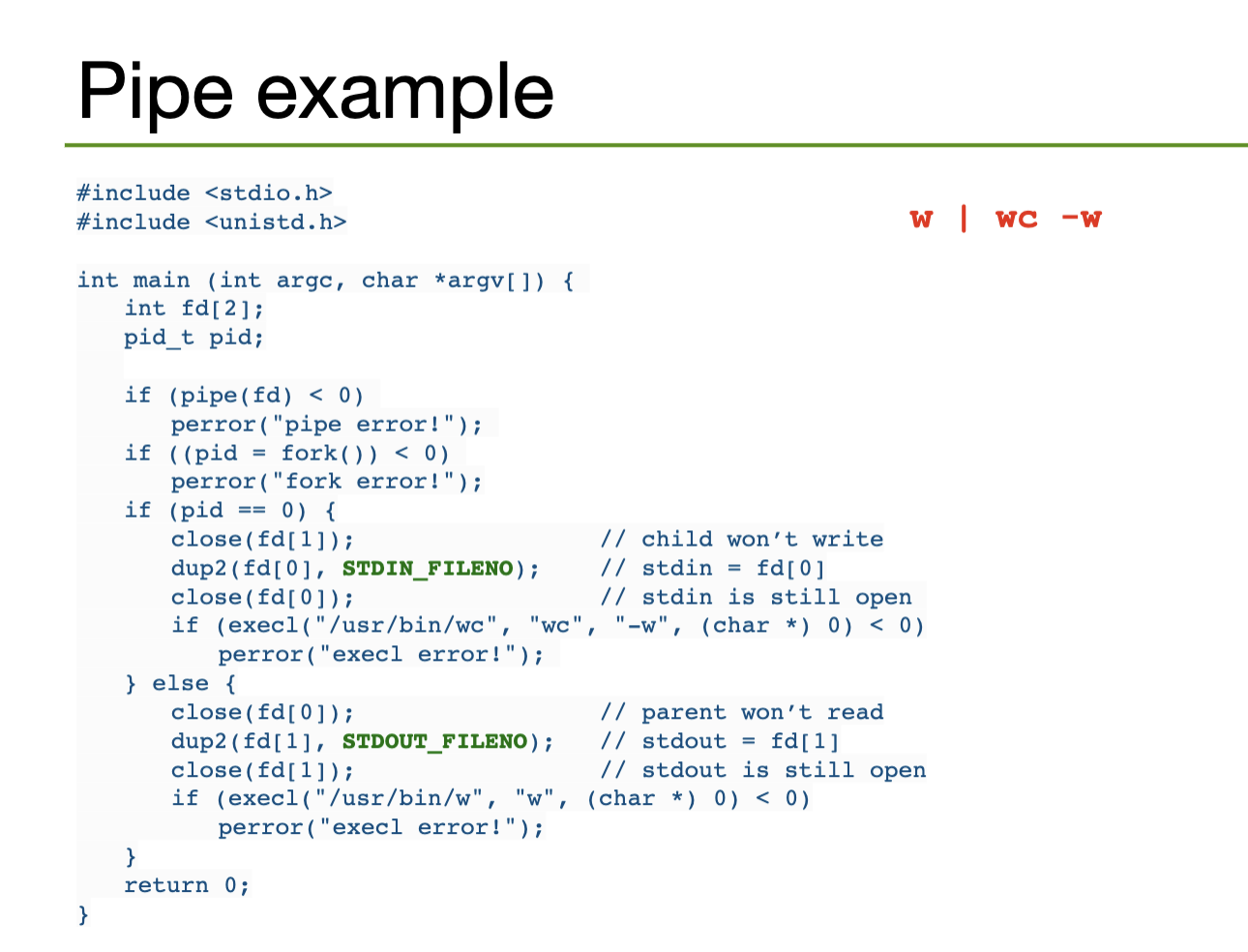

A pipe is a channel established between two processes to communicate; so, they are a form of shared memory (particularly, a lighter one). Pipes imply a producer/consumer relationship.

An ordinary pipe (a.k.a. anonymous pipe also implies a parent-child relationship: the parent creates a pipe, then forks a child process that has access to the pipe too. These are the only processes with access to the pipe.

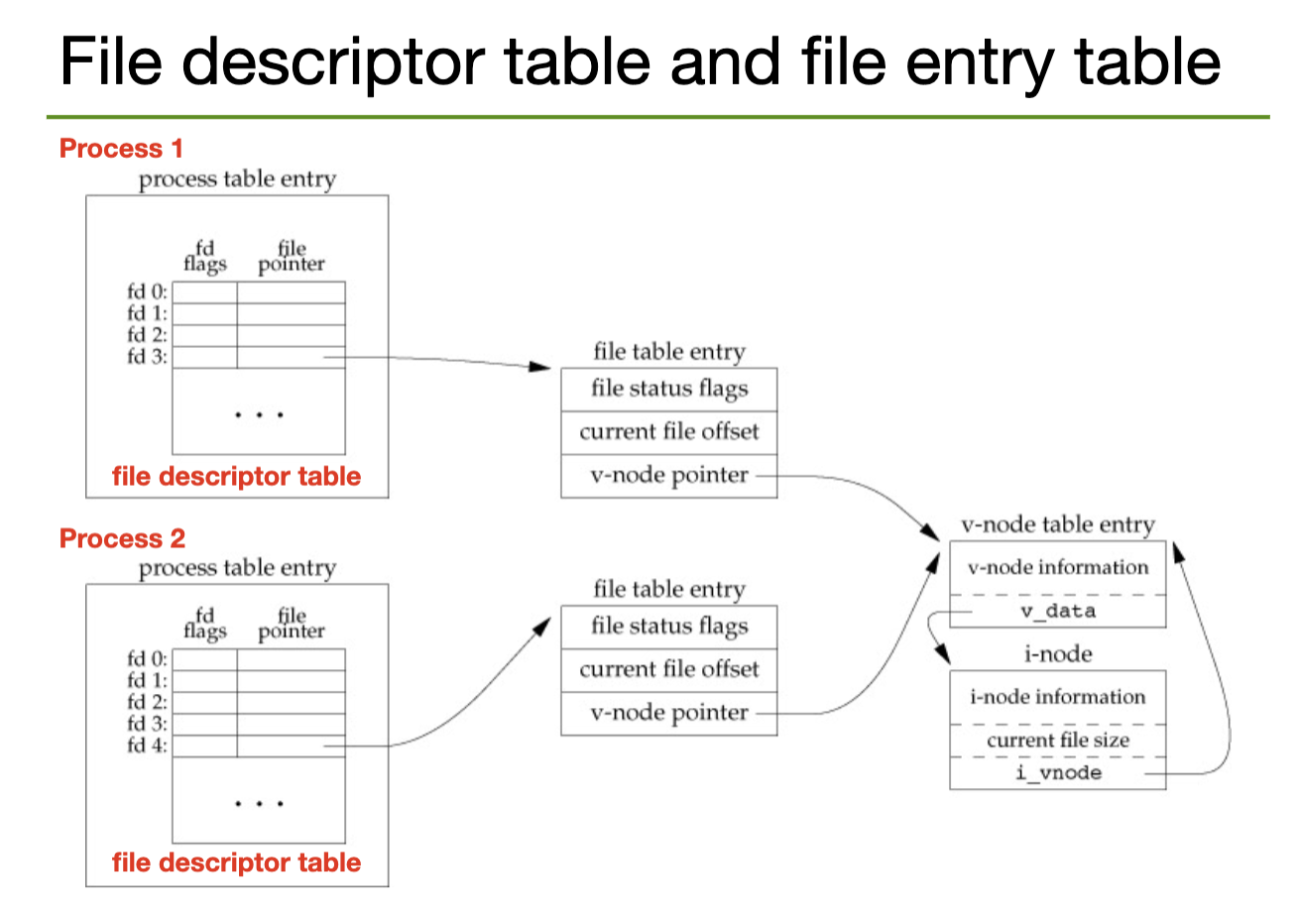

In UNIX, pipes are implemented as special types of files. Thus, they are identified by file descriptors and are manipulated with the read and write syscalls. Namely, we read to consume content and write to produce content. This data pipe flows through the kernel.

0 to indicate EOFSIGPIPE signal// structure to store the necessary file descriptors

int[2] fd;

// create a pipe

pipe(fd);

// the file descriptor for the READ end is stored in fd[0]

// the file descriptor for the WRITE end is stored in fd[1]A file descriptor is an integer index that identifies a file in the kernel's file descriptor table; these are shared between processes. (correctness)

0 is the file descriptor for stdin, 1 for stdout, and 2 for stderr.STDIN_FILENO, STDOUT_FILENO, STDERR_FILENO.File descriptors can be obtained via a syscall by opening a file/pipe/socket/etc, or by inheritance from a parent process.

We can implement I/O redirection by closing a standard stream and re-allocating the corresponding descriptor to another file (or pipe). But there are better ways to do this

// close the standard input

close(STDIN_FILENO);

// set the standard input to read from my file

open("/path/to/my/file", O_RDONLY, STDIN_FILENO);

// we can do this because input is abstracted as a file anyway

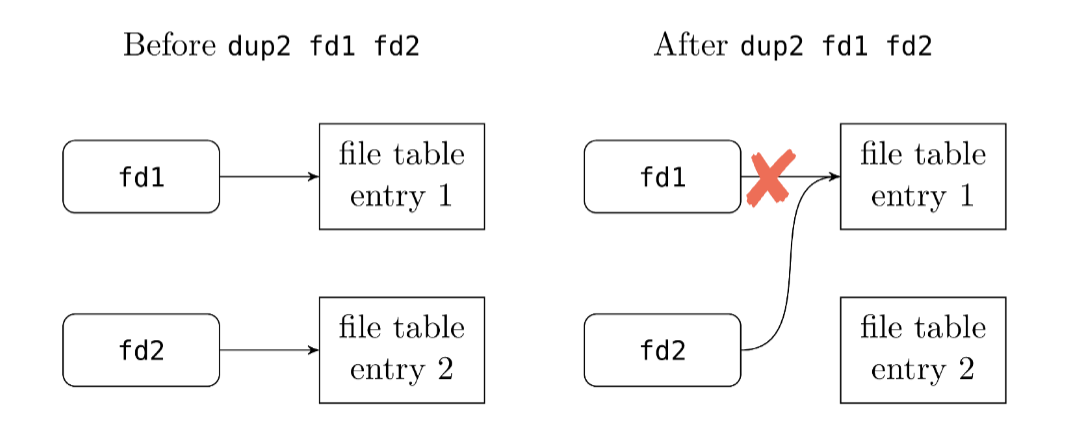

// so feeding in a file directly works since it uses the same interfaceInstead, we can duplicate a file descriptor with the dup2 system call. This creates another reference to the same file descriptor. This way, we can replace it with another descriptor without closing the original file the descriptor points to. (??? what?)

The "pipes as a file" pattern is common in UNIX: many things are implemented as files, e.g. devices, sockets, pipes, actual files, etc. YOU get a file and YOU get a file and YOU get a file.

open, read, write, and close to interact with the file.

To pipe to another process, we would need to create the pipe (i.e. the file descriptors), fork a child process, close the unused ends of the pipe for both processes, call execve to run the command we want in the child process, then wait for the command to terminate. This is annoying and tedious to implement. So, popen() does exactly this.

popen() returns an I/O file pointer to where we need to read from to get the standard output from the child processThen, pclose() closes the standard I/O stream, waits for the command, and returns termination status.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#define LINESIZE 20

int main (int argc, char *argv[]) {

// set up constants and buffer

size_t size=0;

char buf[LINESIZE];

FILE *fp;

// open the pipe

// provide the command we will execve

// we can provide "w" as the second parameter to read instead

fp = popen("ls -l", "r");

// continue reading from the pipe as long as we can

// store the result in the buffer with printf

while(fgets(buf, LINESIZE, fp) != NULL)

// here, we "print" to the buffer instead of standard out

printf("%s\n", buf);

// close the pipe

pclose(fp);

return 0;

}Named pipes (FIFOs in UNIX) generalize ordinary pipes by allowing bidirectional communication between any (possibly several) processes, not just parent-child pairs. Essentially, a named pipe is a named file that any process and read to or write from.

In UNIX, a FIFO is created with the mkfifo syscall and is manipulated like an ordinary pipe, i.e. with open, read, write, close.

Aside: how is a named pipe functionally different from shared memory? they seem really similar

In BASH, we use the character | to open a pipe between two processes; BASH will handle the opening and closing. This pipe redirects the standard output of the left process into the standard input of the right process.

p1 | p2 | p3 …# the pipe identity

./process_1 > temp.file && ./process_2 < temp.file

# equivalent to

./process_1 | ./process_2

Duplication

Hardcoded: w | wc -w

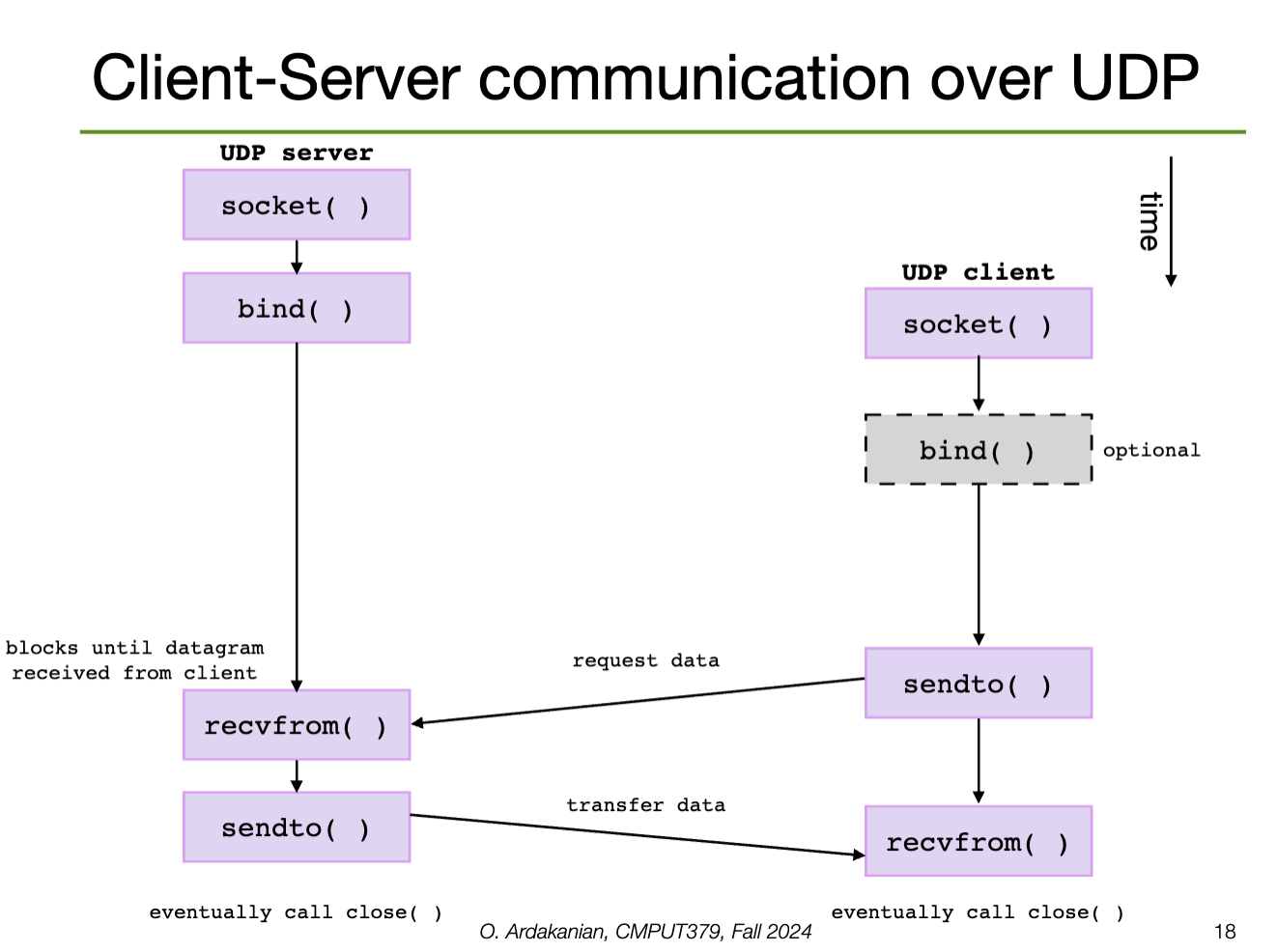

A distributed system is a set of loosely coupled (often physically separate) nodes connected via a communication network, e.g. the internet. Each node has an operating system, as well as its own resources, e.g. a CPU, etc.

Nodes may be configured in a client-server configuration (the server has a resource the client wants to use), a peer-to-peer configuration (each model acts as both a client and a server), or a hybrid model.

Why make a system distributed?

A distributed operating system is capable of migrating data, computation, and processes between its nodes without its user needing to be aware of its internal function. A high level of parallelism is needed to achieve this.

Robustness is the ability of a system to withstand failures. Systems should be fault-tolerant, i.e. able to withstand certain amounts of certain types of failure.

Transparency is how well the system appears as a conventional, centralized system to users (reword, direct copy). The system should act the same way from every access point, e.g. files stored on remote servers should appear like those stored locally to the system's user.

Scalability is the ability of a system to adapt to the increased load from accepting new resources. A system should respond gracefully, i.e. not slow down significantly or fail under increased load.

Consistency is the ability of a system to ensure that its cached local data is consistent with the master data source.

A network is a set of communication links that let multiple computers communicate via packets (the atomic unit of data transmission) through a network interface. A protocol (common set of communication rules) must be adopted across the system.

A local area network (LAN) covers a small geographic area, e.g. a building. LANs connect computers with common peripherals (e.g. printers, storage servers, etc); they must be fast and reliable to be effective. Nodes may connect to a LAN via ethernet or wifi.

A wide area network (WAN) connects geographically separate sites across the world. Its links are serious physical infrastructure, e.g. telephone lines, data lines, optical cables, satellite channels, etc. Due to the distances involved, WAN is slower and less reliable than LAN.

LANs are connected together into WANs.

Network data is divided into packets and flows between switching points; computers at these points control the packet flow. When a packet arrives at its destination, the computer is interrupted.

If packets need to travel between different LANs, a router needs to be used to direct traffic from one network to another. The router reads the packet header to determine the packet's destination, finds the closest node to the destination in a routing table, then forwards packages there.

Packets are accepted by processes, so a <host-name, PID> pair is needed to identify which host and process the packet is meant for. Each process in a system has a unique PID, and each system in a network has a unique name, so this pair alone can identify the process in question.

The domain name system (DNS) is a global distributed database system for resolving hostname-IP (internet protocol) address mappings. These map IPv4 addresses (32-bit integers, e.g. 129.128.5.180) to human-readable names, e.g. gpu.srv.ualberta.ca.

Internet communication is organized into 4 layers of abstraction

The application layer provides a way for processes to exchange data between themselves. The transport layer partitions data into packets, maintains the order of packets, and transfers packets between hosts. The internet layer routes these packets through the network; this involves encoding and decoding addresses. Finally, the link layer handles error transmission over physical media, including the required error correction and detection.

A packet can move through a LAN using only its MAC address. However, if the packet needs to be sent to another system, the address resolution protocol (ARP) must be used to map the MAC address to an IP address.

arp -aEvery host has a name and an associated IP Address; this may be an IPv4 address (32-bit) or an IPv6 address (128-bit).

127.0.0.1Once the host has been located, the receiving or sending process is identified by a port number. This is part of the transport layer; the TCP and UDP protocols are responsible for this. A host has multiple ports → multiple processes can send and receive packets

FTP on port \(21\), SSH on port \(22\), etc.UDP allows for fixed-size messages (datagrams) up to some maximum size. UDP is unreliable: packets may be lost or out of order (although corruption is still checked). UDP is connectionless: no setup or takedown is required, i.e. the process is stateless

TCP is reliable and connection-oriented: it provides abstractions to allow in-order, uninterrupted streaming across an unreliable network. Connections are opened and closed with control packets. The opening consists of a three-way handshake (SYN, SYN + ACK, ACK).

When a host sends a packet, the receiver must send an acknowledgement packet (ACK). If this is not received before a timer expires, the sender will timeout and retransmit the packet. The sender keeps track of the current set of packages sent without being acknowledged.

The sequence counter assigns an order to the packets; the receiver can use this to determine whether packets have been duplicated, i.e. if the original package was received but the original package was lost in transmission.

Sockets are like pipes that go outside

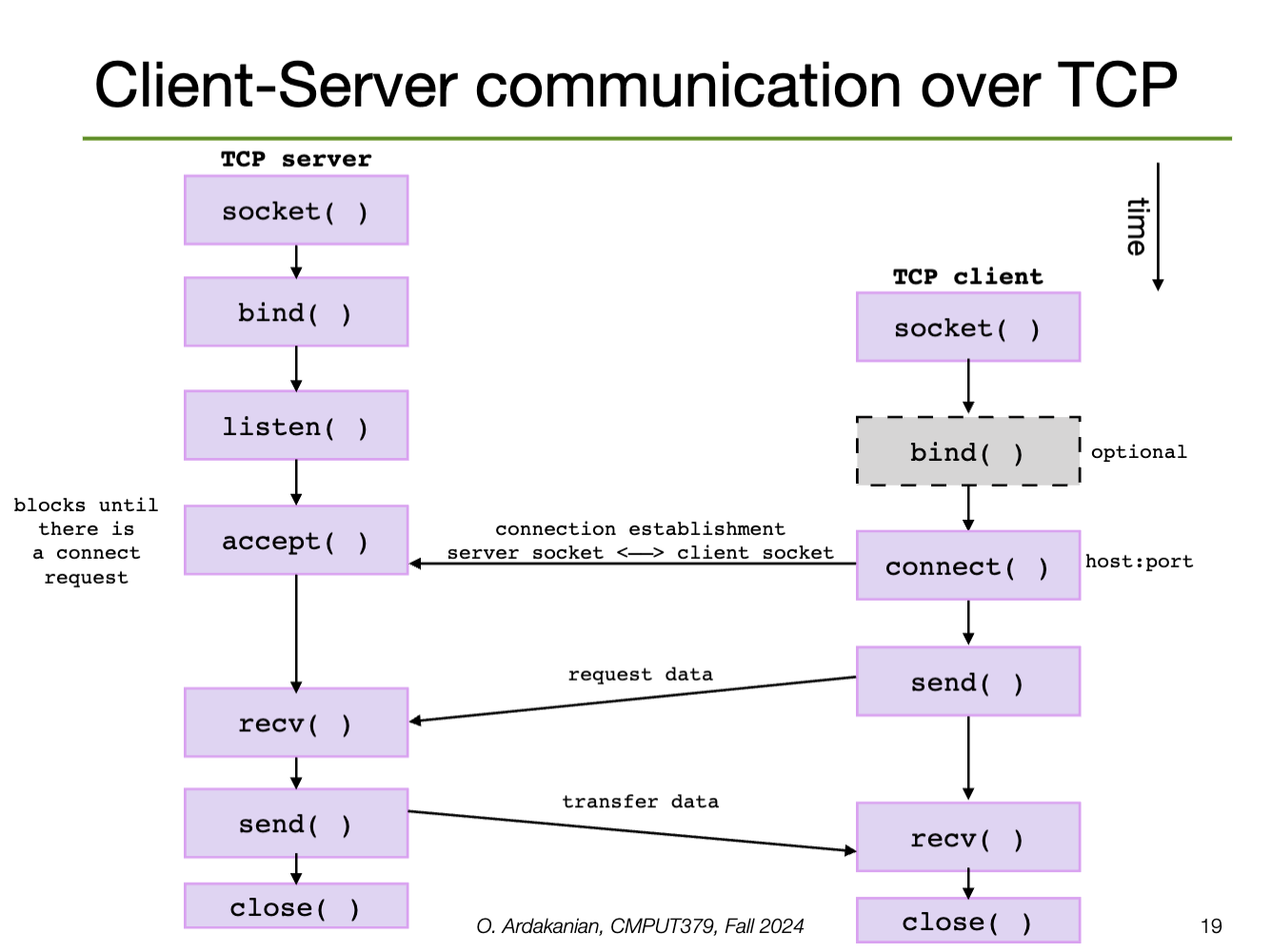

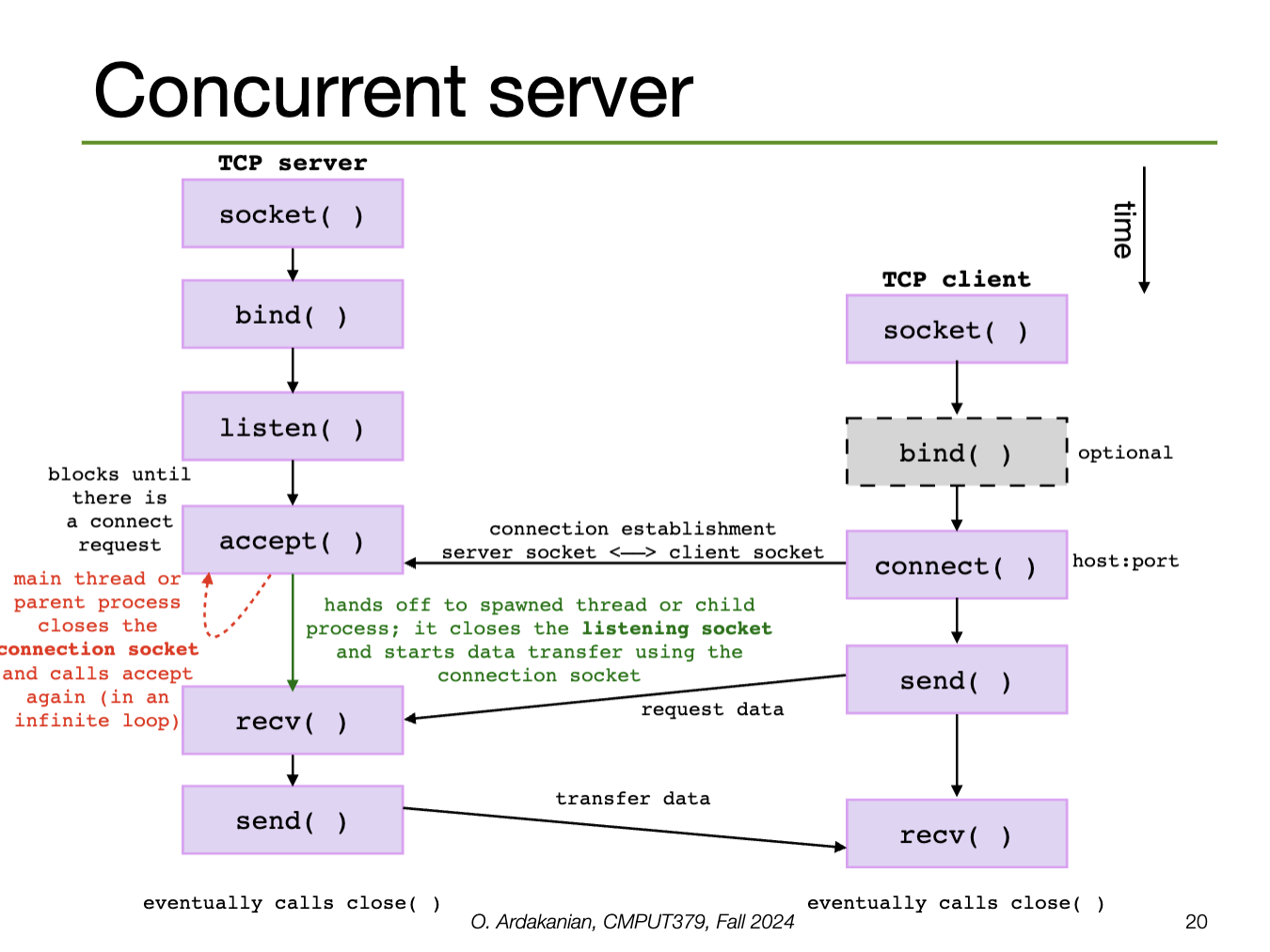

Distributed computing often follows the client-server model: a server provides services (e.g. file service, database service, name service) that a client (process) might request.

A socket is a connection endpoint that provides an abstraction over a network I/O queue. Each endpoint is defined by an IP address and a port number. Communication between two processes requires two sockets, one for each process.

Sockets come in two common types:

A socket supports some set of address domains: address spaces tailored to some aspect of communication (e.g. INET for IP protocols, UNIX domains for processes on the same machine)

sys/socket.hWe create a socket with the socket syscall; this returns a socket descriptor that identifies the socket that was created (or -1 on error).

int socket(int domain, int type, int protocol);AF_INET for IPv4, AF_INET6 for IPv6, AF_UNIX for UNIX domainSOCK_DGRAM for connectionless, SOCK_STREAM for connection oriented message, SOCK_SEQPACKET, etc.UDP, TCP, ICMP, IP, IPv6, etc. 0 sets the default for the given domain and typeSockets work like files; in fact, since this is UNIX, sockets are abstracted by files (of course).

close, read, and write from socketsdup can be used to duplicate a socketshutdown() can be used to disable a socket in one or both directions#include <sys/socket.h>

int sockfd;

// TCP

int sockfd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

// sockfd= socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_TCP);

// UDP

int sockfd= socket(AF_INET, SOCK_DGRAM, 0);

// sockfd= socket(AF_INET, SOCK_DGRAM, IPPROTO_UDP);We can identify the process we want to communicate with by host name (e.g. IPv4) and/or by port number.

addrinfo(name, port_number, …) to get a list of addrinfo structures, each containing a local address.bind()struct addrinfo {

int ai_flags;

// socket domain

int ai_family;

// socket type

int ai_socktype;

// protocol

int ai_protocol;

socklen_t ai_addrlen;

// contains IP address and port number

struct sockaddr *ai_addr;

char *ai_canonname;

struct addrinfo *ai_next;

}Calling socket doesn't assign an address to the socket: we wither need to call bind to associate a port (must be larger than \(1024\)) or leave that choice to the OS when listen or connect is called.

getsockname() can be used to discover the address bound to a socketA connection is uniquely defined by the 5-tuple (source IP address, source port number, destination IP address, destination port number, protocol).

bindA server will call listen (providing the socket descriptor and a number of connect requests to queue) to convert the socket to a listening socket, which start allowing clients to connect.

Then, the server will call accept to create a new connection socket for a particular client connection (from the queue). Thus, accept returns a new socket descriptor for the connection socket so that the original socket is still available to receive requests.

accept blocks until a connection request arrives (unless it is in non-blocking mode)Connection-oriented services (e.g. TCP) require a connection to be established first; this is done by calling connect, which connects a socket to the specified remote socket address.

connect establishes the connection between the two socketsconnect returns -1.We write data with send (connection-oriented) or send-to (connectionless), which take flags.

send blocks until all the data has been transferredsendto requires a destination address for its connectionless socketWe read data with recv (connection-oriented) or recvfrom (connectionless, requires source address), which also take flags.

recv to block until it has received as much data as we requested by using the MSG_WAITALL flag.We can also use read and write to, well, read and write data. However, these aren't socket-specific, so they provide a lower level of abstraction and are more-error prone. The socket-specific functions deal with sockets more cleanly and safely.

poll and select to see and wait for the descriptor to become ready for I/Oread and write don't let us specify flagsTrying to send or receive data on a broken socket creates a SIGPIPE signal.

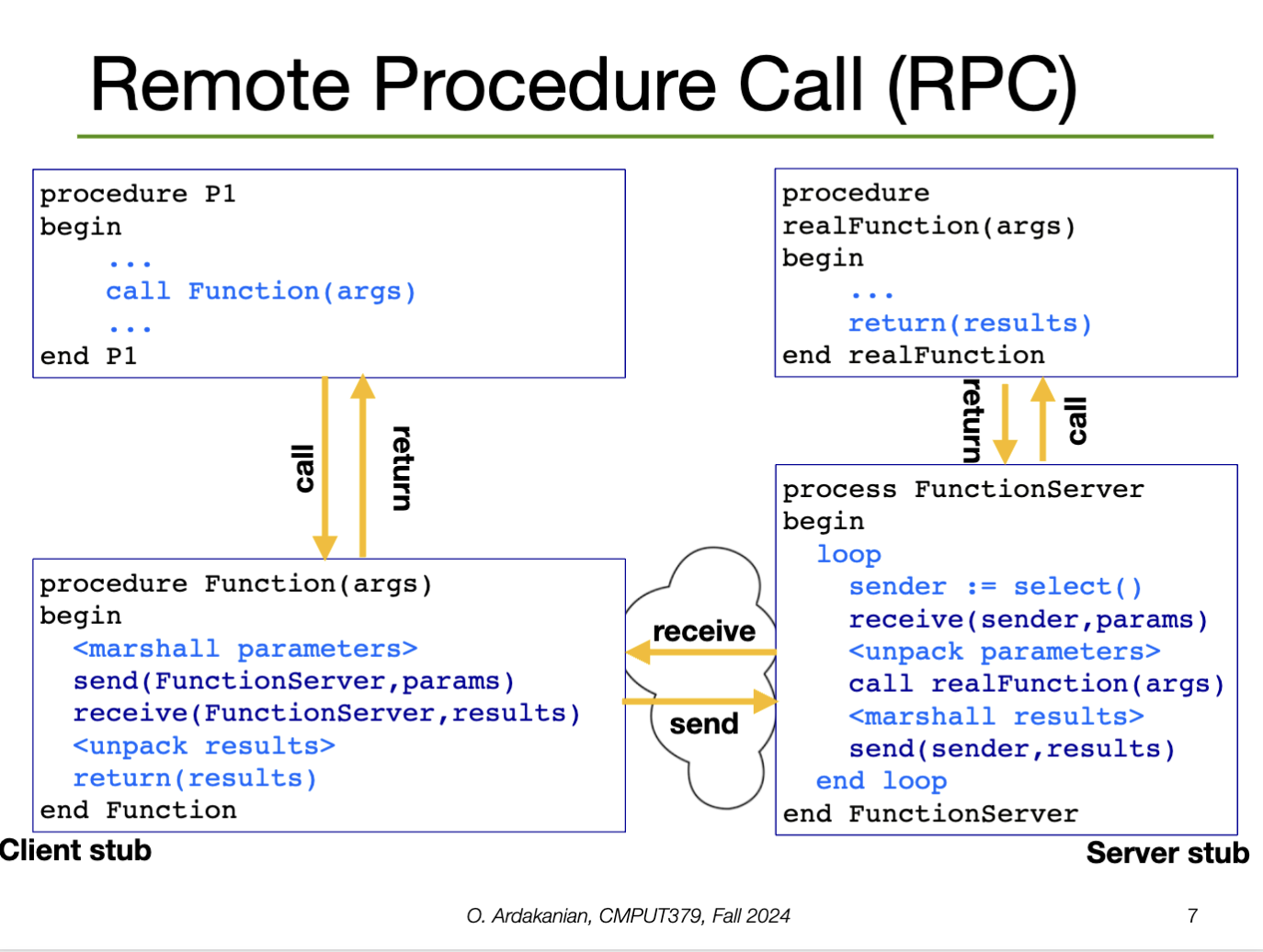

When a local function makes a syscall, the function prepares the arguments and raises the syscall exception, which gets handled by the system call handler. This handler runs, produces the result in a register, then returns control to the function. Easy.

The idea of Remote Procedure Call (RPC) is to make calling syscalls on remote systems as easy as this.

rpcWe need RPCs to implement distributed systems, since a syscall could be made on any device, not just the one that the local process is running on.

The client sets up a message buffer, then reads the function identifier and arguments into the buffer (message serialization or marshalling). Next, the message is sent across a network to the destination RPC server. The client waits for the reply, then unpacks (unmarshalls) the code and returns it to the calling process.

Each message is addressed to an RPC daemon listening to a port on the RPC server. When a message arrives, it is unpacked (unmarshalled), the syscall is made with parameters, re-marshalled, and the reply is sent back.

The RPC server needs a runtime library to handle the tasks related accepting, processing, and sending the data:

How can we best utilize the CPU? I.e. how do we manage the ready queue?

Scheduling is difficult for a few reasons

In particular, processes consist of alternating CPU bursts and I/O bursts. A balanced process has roughly equal composition of CPU and I/O busts; an unbalanced process may favor one more than the other.

// Grammars on the mind

// Can you tell I'm also taking CMPUT 415 this term?

process: (IO_burst)? (CPU_bust IO_burst)+ (CPU_burst)?A workload is a set of tasks for the system to run. Each task has a specific arrival time and burst length; if the system is a real-time system, it also has a deadline.

A performance metric is a criterion that can be used to compare scheduling policies. A scheduling policy is an algorithm that decides the order in which the tasks are executed.

Job scheduling (long-term scheduling) is the process by which the OS decides which and how many jobs should execute in main memory at the same time

CPU scheduling (short-term scheduling) is the process by which the OS picks the next process from the ready queue.

The kernel decides when the scheduler is run. In a preemptive system, the scheduler must wait for a notable event to occur (including a timer interrupt to make sure the scheduler gets run), whereas the scheduler of a non-preemptive system can interrupt a running process to run the scheduler.

Minimizing the average turnaround time is the same as minimizing the time it takes jobs to execute in general; this is the defining problem we are trying to solve. So, turnaround time is probably the most telling metric, and the one we focus on.

Clearly, it is not possible to optimize all of these criteria at the same time (or is it?). So, we choose a policy to optimize a metric, which may involve optimizing one or more of the following criteria:

I think I posted a reel to this song

For the scheduling algorithms we will cover, we assume each user has a single process, which has a single thread, and the machine has one processing core. All processes are assumed to be independent.

These are not realistic assumptions for modern computers. However, developing scheduling algorithms under relaxation of the above assumptions is still largely an open problem.

Part II contains algorithms. Yay!!

make some cool diagrams for this!

First-come-first-served scheduling

AlgorithmSo, FCFS runs only when a job gets blocks because it is waiting for I/O (i.e. it is non-preemptive)

This algorithm is simple to implement and has low overhead.

Since the order of tasks remains unchanged, short jobs can get "stuck" behind long jobs. So, the wait time is highly variable. As the variance of tasks sizes increases, the average response time of FCFS gets longer.

FCFS isn't fair, namely because long tasks take up time directly proportional to their length, by definition.

Finally, overlap between the CPU and I/O is clunky because CPU-heavy processes will force I/O-heavy processes to wait, leaving the I/O devices idle for (possibly long) periods of time. This degrades the experience of the user.

Round-Robin Scheduling

AlgorithmIf \(Q\) is too long, waiting time increases and round-robin degenerates to FCFS as \(Q \to \infty\), since processes are preempted less and less. If \(Q\) is too short, a higher percentage of time is spent on context switching (which increases at \(O(N)\) since the "context switch time" is constant), increasing overhead.

Round-robin is pretty good; most systems today use it.

Round-robin is fair, by definition.

If tasks are equal in size, average waiting time can suffer if there is "constructive interference" between the quantum length (\(Q\)) and the length of the tasks. Namely, if the task length is slightly longer than a multiple of \(Q\), then tasks that are almost done are added back to the queue. Next time the scheduler passes through the queue, each task ends quickly, increasing context-switch overhead.

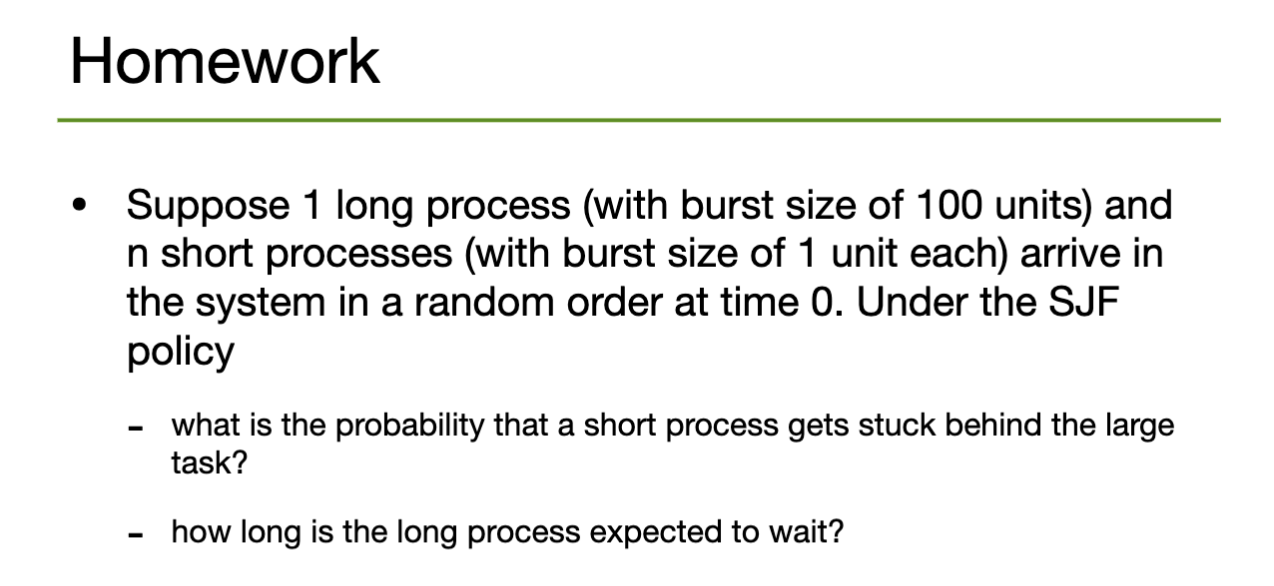

SJF/SRTF Scheduling

AlgorithmGenerally, we apply the concept of temporal locality: we estimate the next burst length we will see using the previous burst lengths we already saw. In particular, the exponential moving average estimator \(\hat{b}\), defined by \(\left\{ \begin{array}{ll}\hat{b}(1) := \hat{b}(1) \\ \hat{b}(t) := \eta \times \hat{b}(t) + (1-\eta) \times \hat{b}(t-1) & \text{ for } \eta \in (0, 1] \end{array}\right.\).

SJF is provably optimal for minimizing average waiting time, and is compatible with both preemptive and non-preemptive schedulers.

It is not possible to accurately predict the amount of CPU time a process will need ahead of time (so then why is this here? is it impossible, or are we just bad at it. Is there a bound on how good we can get at it? is it an active area of research?). Under this assumption, SRTF degenerates into picking tasks pseudo-randomly.

If new short jobs keep arriving in the queue, a long-running CPU task may starve, i.e. never be allocated resources.

aside: do this! it's cool.

Can we design a policy that minimizes response time, is fair and starvation-free, with low overhead?

We can annotated each task with a (usually) user-defined priority that indicates how important they are. Then, we keep multiple queues, one for each priority level.

However, if the scheduler simply picks from the highest priority queue that isn't empty, jobs are prone to starvation again. Instead we can

These solutions may increase average response time, but optimize fairness.

If a high-priority task is blocked by a lower-priority task, the high-priority task may grant its high priority to the low-priority task so that it can run on its behalf. Once the low-priority task is finished, the high-priority task can run again

Multi-level Feedback Queue (MFQ) Scheduling

AlgorithmNote that any improvement to fairness will come from giving long jobs more CPU time, which degrades average wait time. Some "solutions":

Lottery Scheduling

AlgorithmSo, the share of CPU cycles allocated to a job is probabilistically proportional to the number of tickets assigned to each job. Thus, the priority of a job corresponds to how many tickets are given to it. Every job is given at least one ticket to avoid starvation

So, performance degrades gracefully as the load changes because the effect of adding or removing a process is probabilistically "spread out" over all existing processes equally.

There are two approaches

Aside: a common read queue system would exponentially alleviate the problems with other algorithms, right? since a single core isn't blocking anything or can we just abstract this away as stuff we've seen already? look into this

A real-time system is a system where each task specifies a deadline by which it must be completed. In a soft real-time system, failing to meet the deadline leads to degradation in performance. In a hard real-time system, missed deadlines cause the system to fail entirely.

Soft real-time systems often use a preemptive, priority-based scheduler that assigns real-time tasks to the highest priority. E.g. in Windows, priority levels \(16\)-\(32\) are reserved for real-time processes (\(32\) is the highest level).

Hard real-time systems require the use of admission control: the scheduler can only accept a task if it can guarantee it will finish execution by the deadline. Otherwise, the scheduler rejects the task

A periodic tasks has a fixed deadline \(d\), processing time \(t\), and will require the CPU at constant interval \(p\). So, (for any of this to have a chance of working) we must have \(0\leq t\leq d\leq p\). The task will need \(\dfrac{t}{p}\) of the CPU's time.

Rate-Monotonic Scheduling

AlgorithmEarliest-deadline-first (EDF) Scheduling

AlgorithmIf a feasible schedule exists, EDF is theoretically optimal with respect to CPU utilization. However, if no schedule exists, EDF may cause more tasks to miss their deadlines than is necessary.

We define the laxity or slack time as \(\text{time until deadline } - \text{ remaining execution time required}\) \(=\text{deadline }-\text{ current time }-\text{ remaining execution time required}\).

Least-Laxity-First (LLF) Scheduling

AlgorithmSo, LLF is essentially a refinement of EDF, inheriting from the definition of laxity as a refinement of "time until deadline". The overall structures are the same; it's just the "cost function" that's different.

Threads are the next level down from processes; threads of a process execute on the same program at the same time, using the same address space. They can further "split" tasks, but incur less costs than using separate processes.

Modern systems have multiple processing cores and the OS needs to handle many things at once. So, introducing parallelism has the potential to improve performance. A process with multiple threads has multiple "little pieces" that can run in parallel.

E.g. a web browser may have a thread to render the HTML and CSS, another to retrieve data from the network, another for responding to user input, etc. Thus, all of these things can happen at the same time.

E.g. a web server executing multiple threads concurrently

E.g. the kernel of an operating system is multi-threaded; each thread performs a specific task, e.g. device management, memory management, interrupt handling, etc.

A thread is a single stream of execution within a process presenting an independently schedulable task. So, each process must have one or more threads, i.e. one or more points of execution.

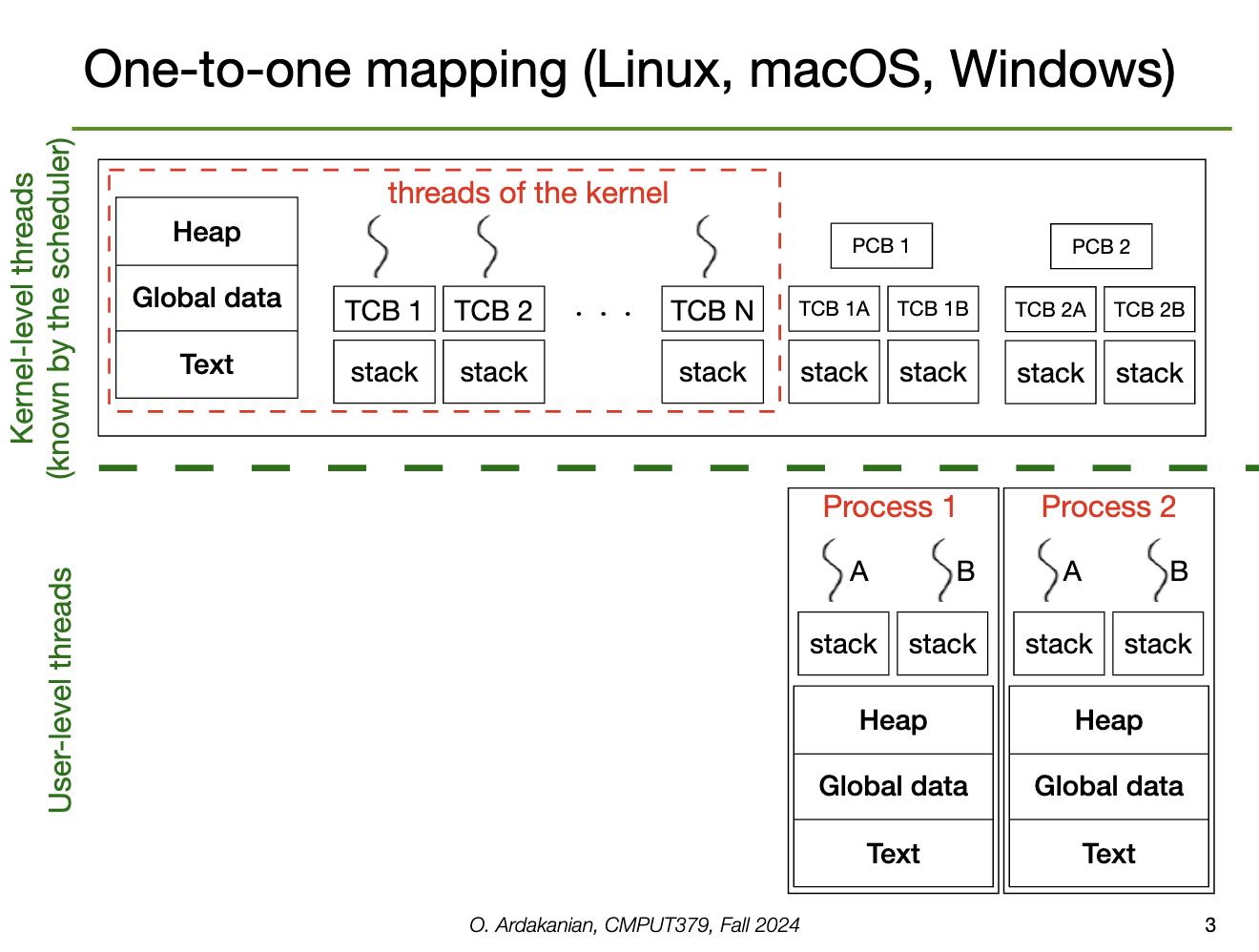

Each thread has a thread ID (analogous to a process ID), a program counter, a stack pointer (and thus its own stack), and a set of registers to use. However, the heap, text, and data sections are shared with the rest of the threads in the process, as well as other OS resources (e.g. open files, signals)

The resources unique to a thread are stored in the thread control block (TCB), analogous to the process control block. This may also include thread-local storage (TLS), which is accessible in a thread because it persists across function calls (i.e. works differently than the stack).

The address space of a process is shared among its threads, i.e. many threads exist in one protection domain.

Since each thread of a multi-threaded process shares the heap, data, files, etc, data-sharing is much easier and does not require syscalls, message passing, shared memory, etc.

If two threads run successively on a single processor, a context switch is still required because the PC and registers must be replaced. However, since the address space is the same, context switches between threads are less expensive.

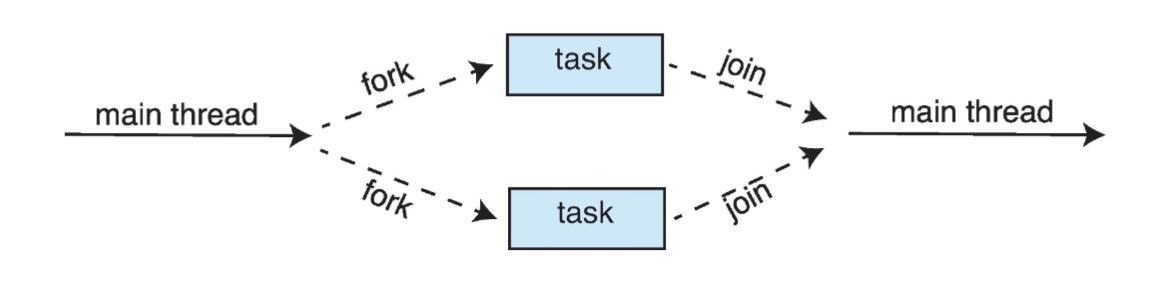

Order between threads is not specified or guaranteed, so threads may run in arbitrary order. Thus, we can design the program so all the threads can execute concurrently (asynchronous threading) or force the main thread to wait until the other threads terminate (synchronous threading).

#define N 100;

int in, out;

int buffer[N];

void producer() {

//...

}

void consumer() {

//...

}

int main() {

in = 0;

out = 0;

// we could also use pthread_create, which takes a function pointer

fork_thread(producer());

fork_thread(consumer());

// ...

}fork_thread twice: the main thread and the two new threads.fork_thread or pthread_create to create new threadsWe can quantify performance gain with Amdahl's law: If a system has \(S\%\) serial (i.e. sequential) components and thus \((1-S)\%\) parallel components, then we have the bound \(\boxed{\displaystyle\text{speedup with respect to adding new cores }\leq \left({S+\dfrac{1-S}{N}}\right)^{-1}}\) where the system has \(N\) processing cores.

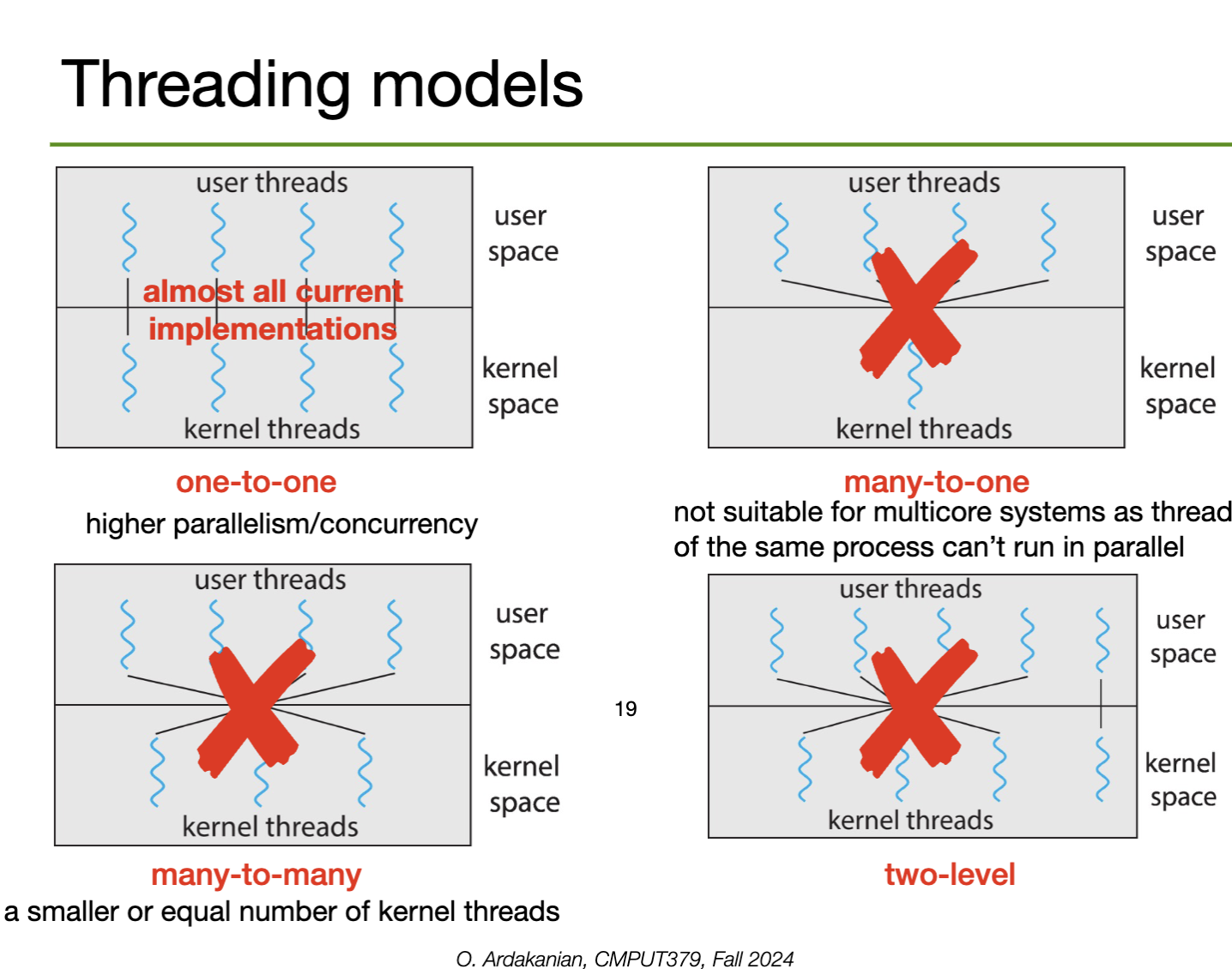

We have two types of threads: user threads and kernel threads.

A kernel thread (or lightweight process) is a thread directly managed by the OS; the kernel manages and schedules it.

A user-level thread is a thread that the OS is not aware of. Instead, the programmer uses a thread library (e.g. C-threads) to implement and manage the threads in code. This library handles the creation, synchronization, and scheduling of the threads instead of the OS.

Since the OS doesn't know about the user-level threads, it can't use them to make scheduling decisions, decreasing the performance of the scheduler. Solving this problems requires the thread library to communicate with the kernel, which would require syscalls.

Thus, the user and kernel threads must communicate in some configuration: one-to-one (high parallelism and concurrency, used in most current implementations), many-to-one (doesn't work for multicore systems since threads of the same process can't be parallelized), many-to-many (lets us use less kernel threads than user threads) or two-level (hybrid).

A system is parallel if more than one task at the same time. Multi-threading can improve the parallelism of a program.

A system is concurrent if all of its tasks can make progress at any given time*. This can be implemented by switching quickly between processes, and thus does not require multi-threading.

Tasks must be identified and split in such a way that they are independent and can be run in parallel. They should also perform equal amounts (and value) or work for effective load balancing. Distributing tasks across cores is the core aim of task parallelism.

If there is dependency between data accessed by multiple tasks, the task execution must be synchronized, i.e. we need to make sure that conflicting tasks don't run at the same time.

Testing and debugging get much harder in multithreaded applications because execution happens in multiple places and has elements of non-determinism (e.g. due to no guarantees on thread order).

forking In Multithreaded Programs?fork has two versions: one the duplicates all the threads of the parent process, and one that creates a single-threaded child process. Generally, the thread copied is the one that called fork in the first place

exec is called right after fork, duplicating all the threads is a waste of time and memory because the exec call replaces the whole memory of the process containing the threads.Under implicit threading, thread creation and management is left to the compiler and run-time libraries of a program. Thus, programmers just need to identify tasks that can run in parallel in their programs; the infrastructure they use will do the actual thread allocation for them.

Under explicit threading, a library provides an API for creating and managing threads to the programmer, who must use it to implement the threading manually

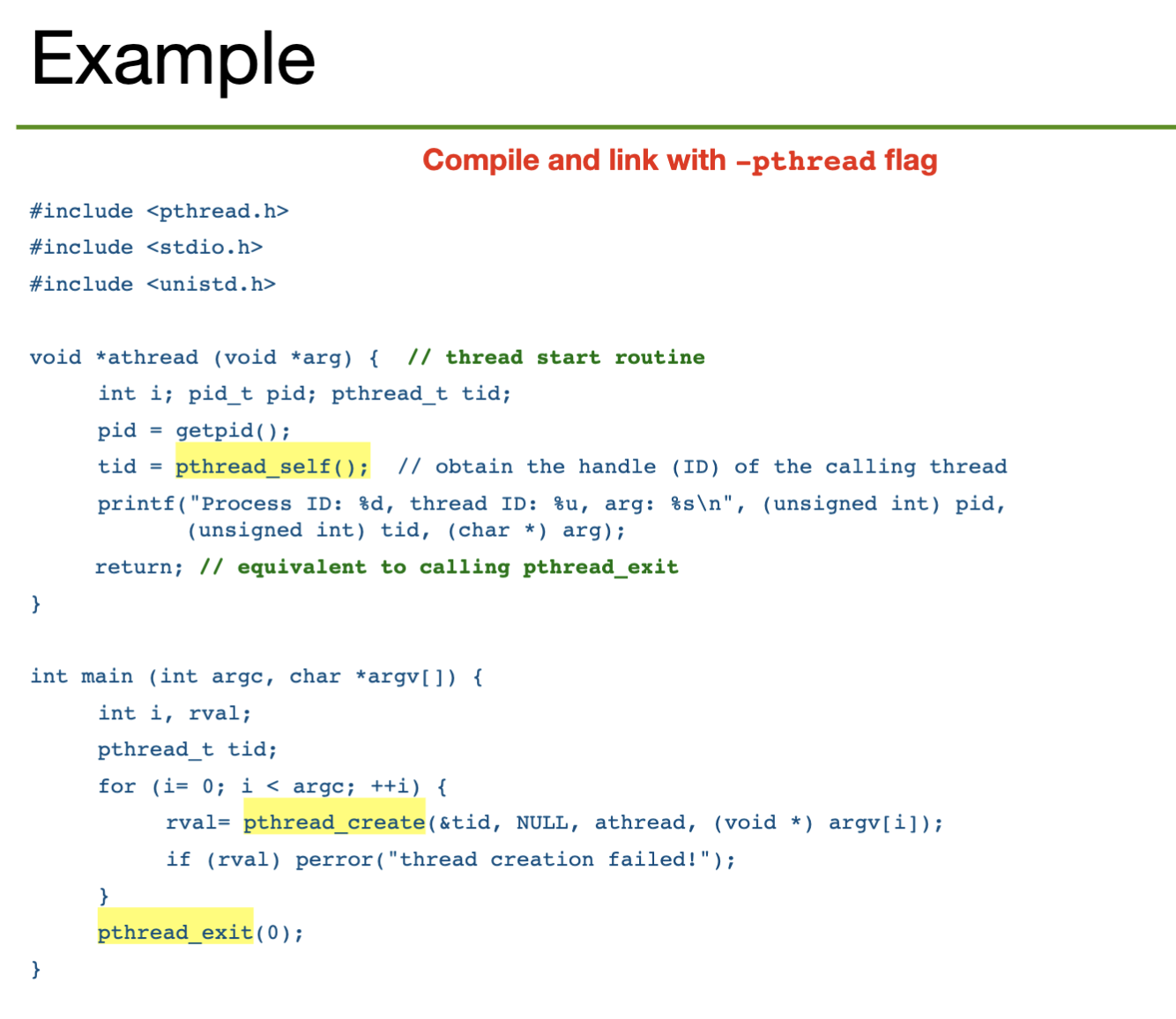

In PThreads, a thread container data type pthread_t acts as a handle of a thread, i.e. something to identify it (like a PID).

man pthread for more information// creates a thread and returns the thread's handle

// we run the routine we want to place in the thread

// directly as a parameter

// aside: how the hell does this work??

// in pratice, implemented with the clone system call

pthread_create(start_coutine());

// allows the initial attributes of the thread to be set

pthread_attr_init();

// blocks the thread that called the new thread until the new thread has terminated

pthread_join();

// causes the calling thread to give up the CPU voluntairly

pthread_yield();

// terminates the calling thread and executes cleanup handlers

pthread_exit();A synchronous signal is delivered directly to the thread that caused the signal to be generated. On the other hand, asynchronous signals (i.e. signals from external events) are sent to the first thread that hasn't blocked that signal, and possibly all the threads that haven't blocked that signal.

POSIX Pthreads has a pthread_kill(pthread_t pid, int signal) function that lets the user send a signal to a specific thread.

Under asynchronous cancellation, a thread will terminate the target thread immediately. Thus, the OS does not have time to react, and might not be able to free/reclaim any resources allocated to the target thread.

Under deferred cancellation, the target thread periodically checks (polls) if it has been cancelled, specifically at cancellation points. If a pending cancellation request is found, the thread will terminate itself and a cleanup handler is invoked to release the thread's resources.

read. So, we can cancel threads blocked while waiting for inputpthread_testcancel)In PThreads, we cancel a thread using pthread_cancel(pthread_t pid). Note that threads can set their own cancellation type with pthread_setcanceltype(); deferred cancellation is the default. A thread may choose to disable cancellation entirely.

A thread pool is a collection of worker threads that execute callback functions for the application, i.e. are passed functions (as arguments) to execute inside the thread. At startup, some fixed number of threads are created; threads wait for tasks to be delegated to them

We can implement a job queue to queue incoming requests; this covers the case when we have more requests than threads in the pool. Once a thread becomes idle, it is "added back to the pool" and the next job in the queue is assigned to it.

Aside: to solve the producer-consumer problem, we might wish to lock access to the job queue and use a condition variable to store whether there is space in the job queue or not.

Under the fork-join model, a thread forks subthreads with fork, passes them arguments, waits for them to complete work in parallel, then joins them with join and combines/processes the results.

This is like a synchronous version of a thread pool; the user (or library, if it uses fork-join to implement something) determines the number of threads that need to be created, which would depend on the number of tasks.

Aside: fork-join follows the structure of divide and conquer algorithms well, implying that they can be easily parallelized under this structure. For example, to implement merge sort, we could fork into two threads to recursively merge sort each half of the list, then join them and collect the results by merging the two lists, as per the definition of the algorithm.

// the server loop is constantly running

serverLoop() {

// blocked by acceptConnection until there is a new connection

connection = AcceptConnection();

// creates a new thread to handle each request that comes in

thread_fork(ServiceRequest, connection);

}Recap: cooperating processes (or threads) share data via message passing or shared memory. However, concurrent access to shared data can lead to inconsistency, so programmers must synchronize access to shared data.

A race condition occurs when the outcome of a program depends on the order in which threads accessing shared data are scheduled. Since this order is not defined, race conditions lead to unpredictable, non-deterministic results.

// initialize: n = ARRAY_SIZE - 1

if (n == ARRAY_SIZE) {

return -1;

}

array[n] = valueA;

n++;If two threads run this code at the same time, there are a few possibilities

Since a certain bug might only happen for a certain interleaving of the threads (which itself is non-deterministic), it can be extremely difficult to debug race conditions.

An operation is atomic if it either runs to completion or not at all. Single instructions may be atomic, but compound instructions (e.g. ones compiled from lines of user code) might not be, e.g. x = x + 1. This includes traditional reading and writing to memory, since we must first load the value, then the address, then write, etc.

If an operation is not atomic, threads may interleave within it, meaning the state of the program directly before and directly after the instruction might be different, with the difference being caused by something unrelated to the instruction.

We can derive that for \(N\) lines of code and \(k\) threads, we have \(\dfrac{(kN)!}{(N!)^k}\) ways to interleave the threads, i.e. ways the different threads may traverse the same program. This corresponds to the number of random walks from the "top-left" to "bottom-right" corners of a \(k\)-dimensional \(N\times \dots\times N\) lattice.

We note that each traversal might not produce a unique result, i.e. multiple different traversals might end up "accomplishing" the same thing. So, this formula doesn't count how many different program outcomes there are.

A critical section is a block of code (a sequential set of programming instructions) that cannot be executed in parallel by multiple threads, i.e. if they were a race condition would occur. Thus, there is mutual exclusion of threads in the critical section: only one can be in there at a time.

To be effective, a critical section must be correct, efficient (entry and exit of the critical section is fast and the critical section is short), flexible (have few restrictions), and support high concurrency.

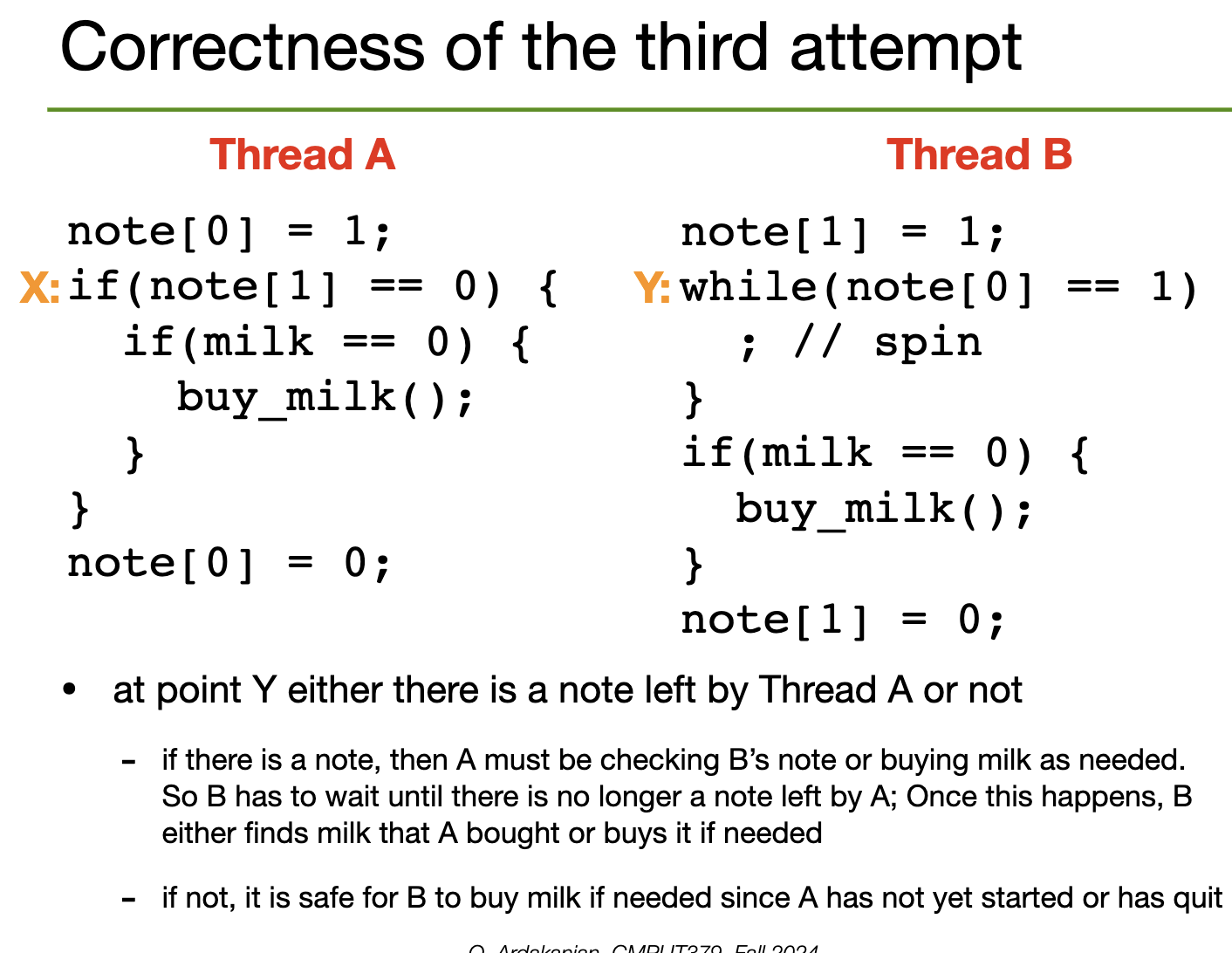

Just leave a note! I.e. have a variable that we store 1 in when a thread is in the critical section and 0 otherwise. Then, before entering the critical section, we just check what the note is.

load and store are atomic and no hardware support is required. This may not actually be true in practice.Just have different notes for each thread, and check each thread's note before entering the critical section. This would be implemented as an array of notes.

We have two notes, but in one of the threads, we spin (stall) until we see that the other thread's note is 0; then we enter the critical section. We implement the spin by having a while(true) look that breaks if the note becomes 0.

1.

This works, strictly speaking, but sucks for a few reasons

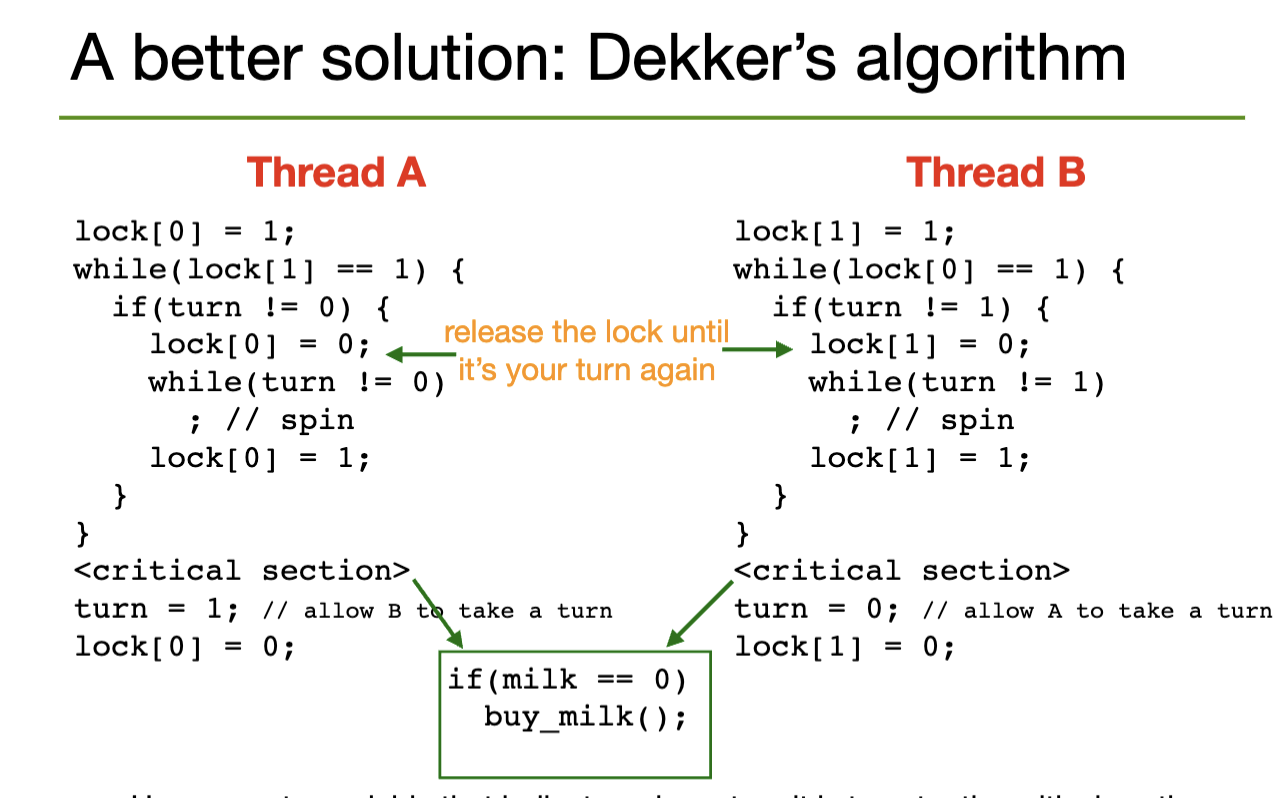

Dekker's Algorithm

Algorithm

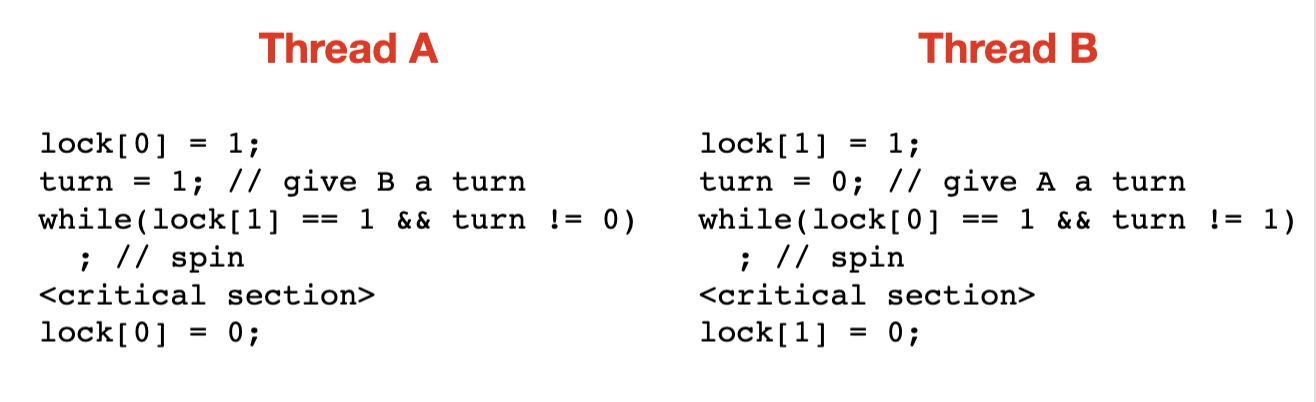

Peterson's algorithm simplifies Dekker's algorithm by merging both while loops into one loop

Peterson's Algorithm

Algorithm1 and give the other process the turn. Then, spin while the other process is locked and the turn is not yours. After that, you are free to enter the critical section, then remove your lock.i only enters the critical section if lock[j] == false or turn == i, both of which are conditions under which it is allowed to access the section.

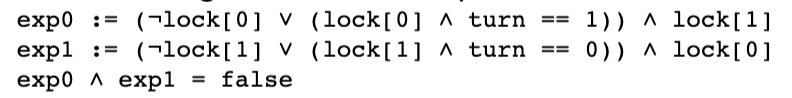

We can prove that the following boolean expressions cannot both be true at the same time; thus, mutual exclusion is guaranteed if the invariant holds before entering the critical section.

Peterson's algorithms is correct, and the solution is symmetric, i.e. the code of both threads "looks the same" (the only difference is which entry in the lock array is accessed). However, it is limited to two threads and requires busy-waiting.

A solution is correct if it has safety (i.e. guarantees mutual exclusion), liveness (guarantees that progress will be made if needed, i.e. a thread waiting to enter an empty critical section will eventually enter it) and a bounded wait time.

To eliminate busy-waiting and lock-contention (only one thread being able to hold a given lock) altogether, we need hardware support for synchronization.

We have three main strategies for hardware-supported synchronization: memory barriers, atomic hardware instructions, and atomic variables (usually implemented with atomic hardware instructions).

Basically, all the synchronization problems come from the fact that a process can be interrupted at any time. So, we find ways to prevent interrupts from being a problem.

The CPU (non-preemptive) scheduler only gets control when internal and external events (i.e. interrupts) happen. So, on uniprocessor systems, we can simply disable interrupts from happening.

In hardware, we implement an atomic read-modify-write instruction that reads a value from memory into a register and writes a new value to it in a single instruction. Thus, it can't be interrupted; the critical section is formed of a single instruction.

Examples: test_and_set in x86 assembly atomically reads a value from memory into a register and writes 1 back to the memory location, exchange atomically swaps between a register and a memory address, compare_and_swap does a conditional swap of values based on the values of some registers.

We can implement a spinlock with test_and_set:

while(true) {

while(test_and_set(&lock));

// we are entering the critical section

// ...

// critical section done

lock = false;

}1 (true), test_and_set will keep reading and writing 1 to itWe can implement a spinlock with compare_and_swap as well

while(true) {

while(compare_and_swap(&lock, 0, 1) != 0);

// we are entering the critical section

// ...

// critical section done

lock = 0;

}compare_and_swap returns 1 when a lock is obtained by another thread by 0 when the lock is free. Since it is atomically set to 1 when the lock is accepted, there can't be a race condition between threads trying to obtain the lockWe can define an increment function that atomically increments a value in memory using compare_and_swap and an atomic variable.

<atomic>, which provides type aliases and operations for all the integral types (i.e. integers, bools, longs, etc). Operations include load, store, exchange, compare_exchange, add, etc.void increment(atomic_int *v) {

int temp;

do {

temp = *v;

} while (temp != (compare_and_swap(v, temp, temp+1)));

}temp is the same as "before"Synchronization primitives must remain invariant over all the threads of a process

Programming languages provide primitive, atomic operations for synchronization. These offer the basic building blocks to create synchronous programs, just like the lambda calculus provides the basic building blocks to create functional programs.

A mutex lock is a high-level programming abstraction of an object that only on thread can hold at a time; it may be implemented with a blocking operation or a spinlock (which uses busy waiting)

Acquire method and a Release method; this the the interface through which it communicates with the rest of the programAcquire blocks until the lock is acquired. So, if the program executes after an Acquire call, the mutex lock must have been acquired (analogous for release)// recall: all threads of a process share the heap

void *malloc (size_t size) {

// assume we have some mutex lock over the heap

// we get the heap lock

heaplock.acquire();

// allocate the memory with syscalls, etc

p = /* the memory */;

// release the lock

heaplock.release();

}

void *free(void *p) {

heaplock.acquire();

// deallocate memory with syscalls, etc

heaplock.release();

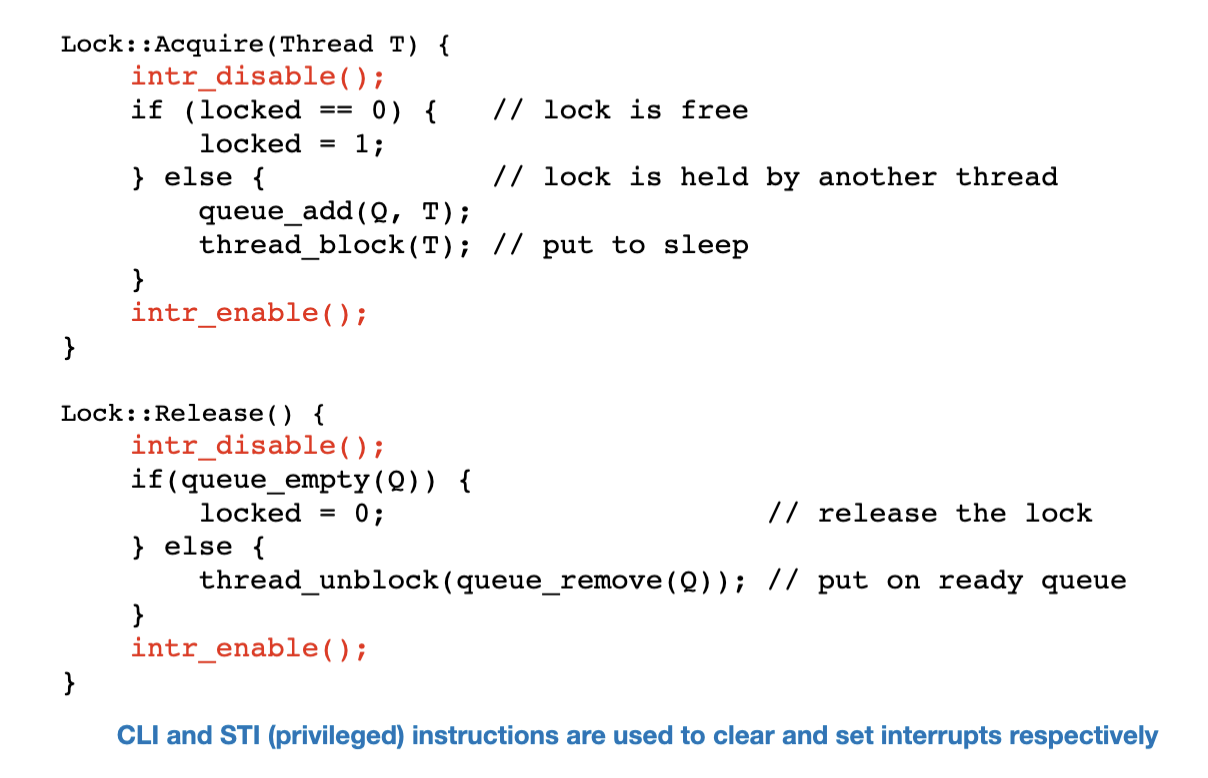

}We can implement mutex locks on uniprocessor systems by disabling interrupts with intr_disable() and re-enabling them with intr_enable(); this happens at the start and end (respectively) of both acquire and release.

This strategy won't work on multiprocessors, since disabling interrupts on one processor won't disable it on the others. So, for multiprocessor systems, we can use instructions like test_and_set or compare_and_swap to implement a busy-waiting loop that atomically checks the status of the lock.

A two-phase lock spins for a small amount of time to see if the lock can be acquired (spin phase). If it can't, the caller is put to sleep (sleep phase). This is a heuristic that assumes temporal locality; if a lock isn't available now, it probably won't be available for awhile.

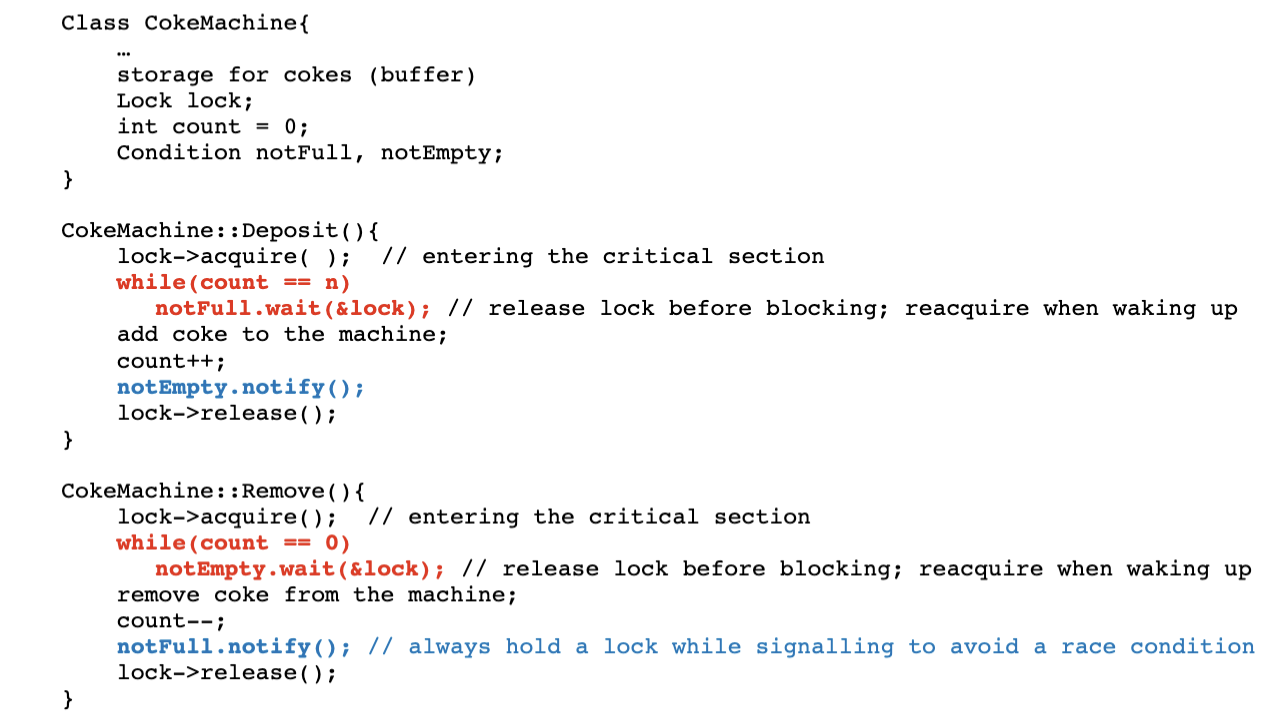

Combined with mutexes, it allow threads to wait in a race-free way for arbitrary conditions to occur; these conditions are stored (as booleans?) in the condition variable

A condition variable is an abstraction that supports conditional synchronization. A queue of threads waits for a specific event that happens in the critical section. So, the value of the condition variable is defined by data protected by a mutex lock.

A condition variable defines three functions:

Wait(), which takes a lock to be released. It atomically releases the lock and goes to sleep, i.e. blocks the thread until signalled. Then, it reacquires the lock when it wakes up.Notify() (historically, signal()), which wakes up a waiting thread and puts it on the ready queue

NotifyAll() (historically, Broadcast()), which wakes up all the waiting threads and puts them on the ready queueWe take the following steps when dealing with a condition variable:

A mutex lock is a device to prevent more than one thread from "moving forward" in the code; the thread must acquire the lock to this, and the "primitive" part is that only one thread can acquire it at a time.

Sometimes, we can implement what we need just with mutex locks. However, whether we need to enter the critical section could be predicated on program state that can only be checked inside the critical section (e.g. if a bounded buffer (which is in the critical section) is full or not). We can't do this with just a mutex lock, since we need it to look in the critical section in the first place.

A condition variable is a primitive that lets us communicate with a mutex lock from inside the critical section. We can call wait on it outside the critical section to block the thread until we call signal (one thread) or broadcast (all threads) from inside the critical section. Thus, we can share information from the critical section without needing to "acquire" the lock in the mutex sense.

We often use a while loop to handle a mutex lock and condition variable:

wait on the condition variable. Under the hood, this releases the mutex lock and pauses the execution of that thread until the condition variable is signaled/broadcastedMy implementation of MapReduce (assignment 2) has good examples of this pattern everywhere.

A semaphore is a generalization of the mutex lock + condition variable pattern: a semaphore has an integer variable (as opposed to the lock, which is a boolean variable) that supports the wait and signal operations.

A semaphore keeps a wait queue of threads waiting to access the critical section. If a thread calls wait and the semaphore is free (i.e. not \(0\)), it grants access and decrements the variable. Otherwise, the process is placed in the wait queue. When signal is called, one process is unblocked and the semaphore is incremented; the next process in the queue is given access.

count variable, a condition variable to check the count, and a mutex lock to protect accesses to count.Mutual exclusion can be implemented by a binary semaphore by calling wait directly before the critical section and signal directly after. Used this way, a counting semaphore would let at most \(k\in \mathbb{N}\) threads into the critical section at a time.

Unlike with condition variables, calling signal on a semaphore with an empty queue does have side effects: it still increment's the semaphore's count, which gets decremented the next time wait is called. Calling signal on a "empty" condition variable does nothing until a thread calls wait.

A monitor is an abstract encapsulation of a lock and a number of condition variables into a class. It hides the synchronization primitives behind this class interface; the user of the monitor interacts with the critical section through thread-safe methods, which access the critical section's data.