Dataflow equations

EquationCMPUT415Lexical Error: A token not in the vocabulary (lexicon) is not in the phrase Parsing error/Syntax error: the phrase is not part of the valid language that is recognized by the grammar Semantic error: The input is grammatically correct but semantically meaningless

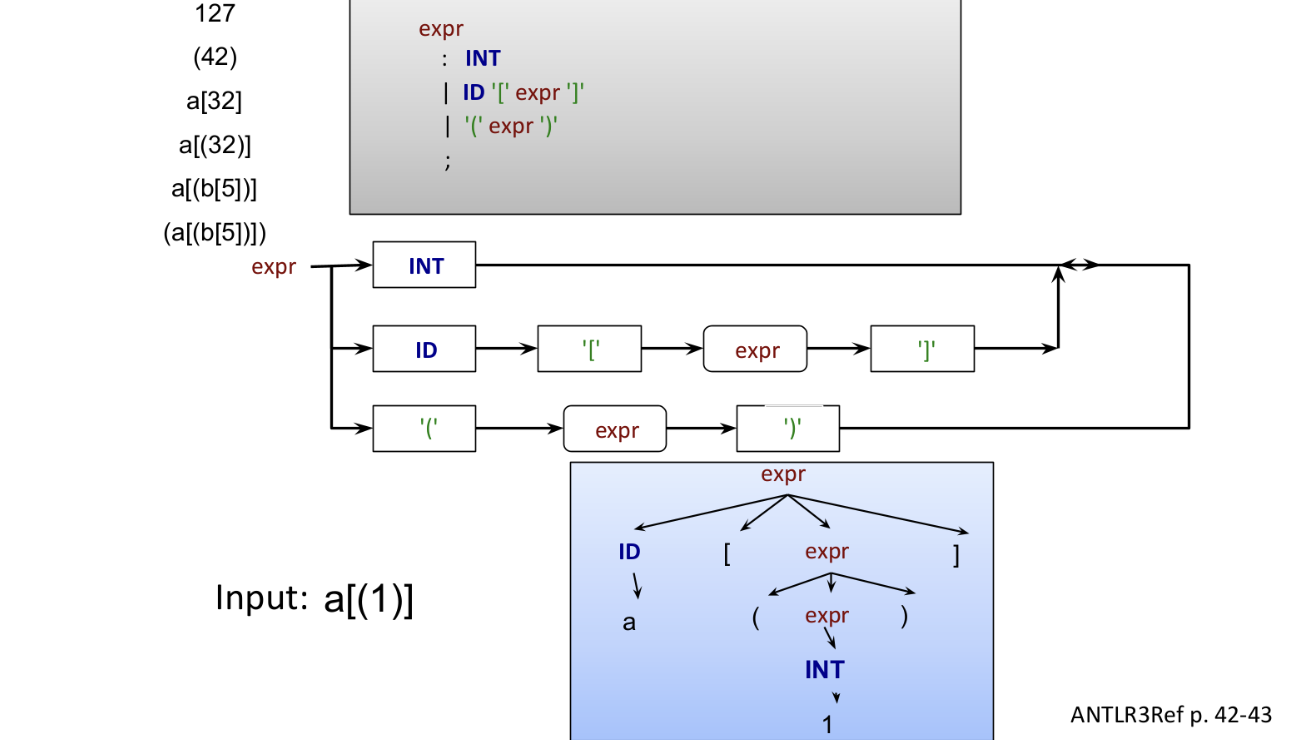

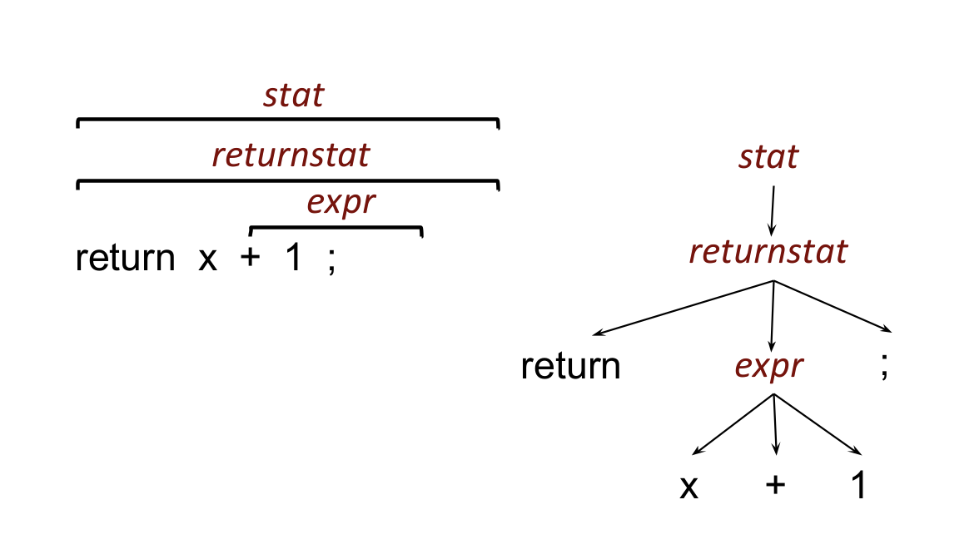

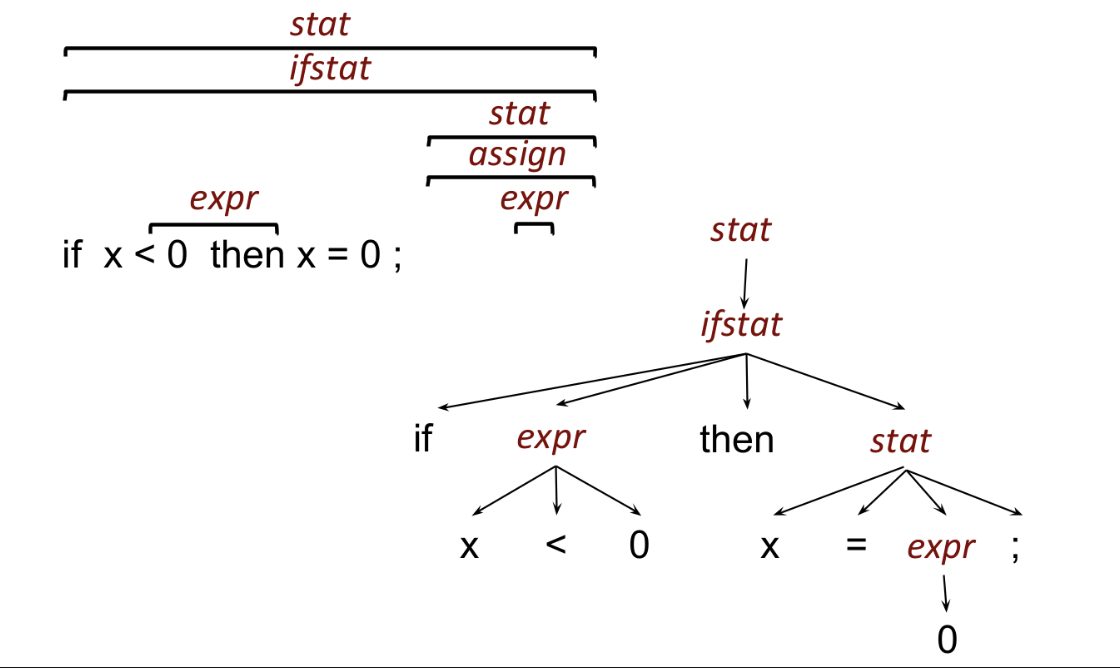

The input is in the form of a stream of characters. The lexer/tokenizer groups this stream of characters into a stream of tokens, which are the atomic units of the language. Next, a parser builds the token stream into a parse tree by matching patterns of tokens to parser rules in the grammar, which describes how tokens form sentences.

The parse tree may be further refined (e.g. into an AST), then used for something semantically meaningful. An interpreter would traverse this tree and evaluate the computation following the structure of the tree itself. A compiler would translate the tree into another program in a lower-level language.

Note that ancillary data structures (e.g. symbol table, flow graph, scope tree, etc.) may be required to properly evaluate/compile the program.

Regular expressions are particularly useful for parsing, since they perform the same task that the parser does, just one level down; regex deals with individual characters. As such, they are particularly useful for matching tokens.

grammar Generator;

// a file is a bunch of statements

file: stmt* EOF;

// operator precendence is encoded in these rules

expr: '(' expr ')' #parenExpr

| <assoc=right> expr op=EXP expr #expExpr

| expr (op=MUL | op=DIV | op=MOD) expr #mulDivModExpr

| expr (op=ADD | op=SUB) expr #addSubExpr

| INT #intExpr

| ID #idExpr

;

stmt: '[' ID IN INT '..' INT '|' expr']' ';';

// TOKENS

// reserved words

// these should be at the top so they match before other stuff

IN: 'in' ;

// integers

INT: [0-9]+ ;

// identifiers

ID: [a-zA-Z][a-zA-Z0-9]* ;

// operator tokens

ADD: '+';

SUB: '-';

MUL: '*';

DIV: '/';

MOD: '%';

EXP: '^';

// to skip

WS: [ \t\r\n]+ -> skip;

LINE_COMMENT: '//' .*? ('\n' | EOF) -> skip;A few notes

<assoc=right> tag to force the grammar to parse from the rightop= tags for particular entries in grammar rules to "group" them together; this makes them easier to manage later.#tags to abstract out the parsing of each rule case (with |) into its own handler in the backend-> skip tells ANTLR to skip over whatever matches the rule; this is often used for whitespace, comments, etc.Regular expressions reference: https://docs.workato.com/regex.html

We define a function getNextToken() that grabs the next token from the input stream. Then, we have a main conditional with an entry corresponding to each type of token; the expression in the if-statement more or less matches the regular expression to match the first character.

Inside each conditional body, we know which type of token we are trying to recognize. So, we continue fetching tokens from the input stream (in another while loop) until we fail to match the rule that recognizes characters in the token. At this point, we return the token (or, alternatively, the index that it ends at).

For single character tokens, we simply check if the character is equal to each token. We can use a switch statement for this because the order of conditionals will not matter.

The lexer simply calls getNextToken() until there are no tokens left.

The lexer matches the longest expression that it can; it only stops matching when it finds a character that cannot be in the token. It's then that it returns.

The lexer is also do or die; once it matches to a specific type of token, it fetches from the input stream until it matches the token completely as described above. So, if it matches something we don't want it to, it will keep burning the input stream; those characters will be gone forever.

Finally, the order of the conditionals matters; the lexer will try to match to rules in order, so if a character can match to multiple tokens, the lexer will pick the first one. So, the order of rules in the grammar does make a difference if there exist characters that could be the first character of multiple tokens.

In this example, we parse words and numbers.

// enum with ID and INT

Token getNextToken() {

// skip whitespace

do { c = getchar(); } while (c == ' ' || c == '\n');

// if starting to lex a word

// [a-zA-Z]

if('a' <= c <= 'z' || 'A' <= c <= 'Z') {

// lex the rest of the word

// [a-zA-Z]*

do { c = getchar(); } while ('a' <= c <= 'z' || 'A' <= c <= 'Z');

// return whatever (we would keep track of it before)

return ID;

}

// if starting to lex a number

// [0-9]

if('0' <= c <= '9') {

// [0-9]*

// lex the rest of the number

do { c = getchar(); } while ('0' <= c <= '9');

// return whatever (we would keep track of it before)

return INT;

}

}We are given a stream of tokens. Like the lexer, we check the value of the first token, pick the corresponding rule, then read the token stream until we match a complete rule.

It is useful to define a match(TOKEN) function that fetches the next token from the stream and makes sure that it is of the correct type.

We also define a function for each type of rule that parses it. This "rule function" can recursively call other "rule function"s.

Finally, this example has a lookahead. This peeks at the next token in the stream. Sometimes, this is needed to figure out which case we need, e.g. if we have a recursive expr that can be expr + expr, expr - expr, etc.

// recognize a statement

void statement() {

// there are multiple types of statements

// so the statement function just delegates to these

// it's a "RULE -> RULE" rule, kinda like syntactic sugar

switch(cur_token) {

case ID:

assign_stmt();

break;

case IF:

if_stmt();

break;

case WHILE;

while_stmt();

break;

// ...

}

}

void assign_stmt() {

// assign_stmt: ID = expr ;

// this is an "and"/"product" in the sense that there's an

// ID and a EQUALS and an expr and a semicolon

// so, the matching happens in succession instead of as an if/switch

// further cements the orifsum and andthenprod

match(ID);

match(EQUAL);

expr();

match(SC);

}

// ????????? seems iffy

void expr() {

match(INT);

// foreshadowing

if(!lookahead('+')) {

return;

}

match('+');

expr();

}this code looks iffy

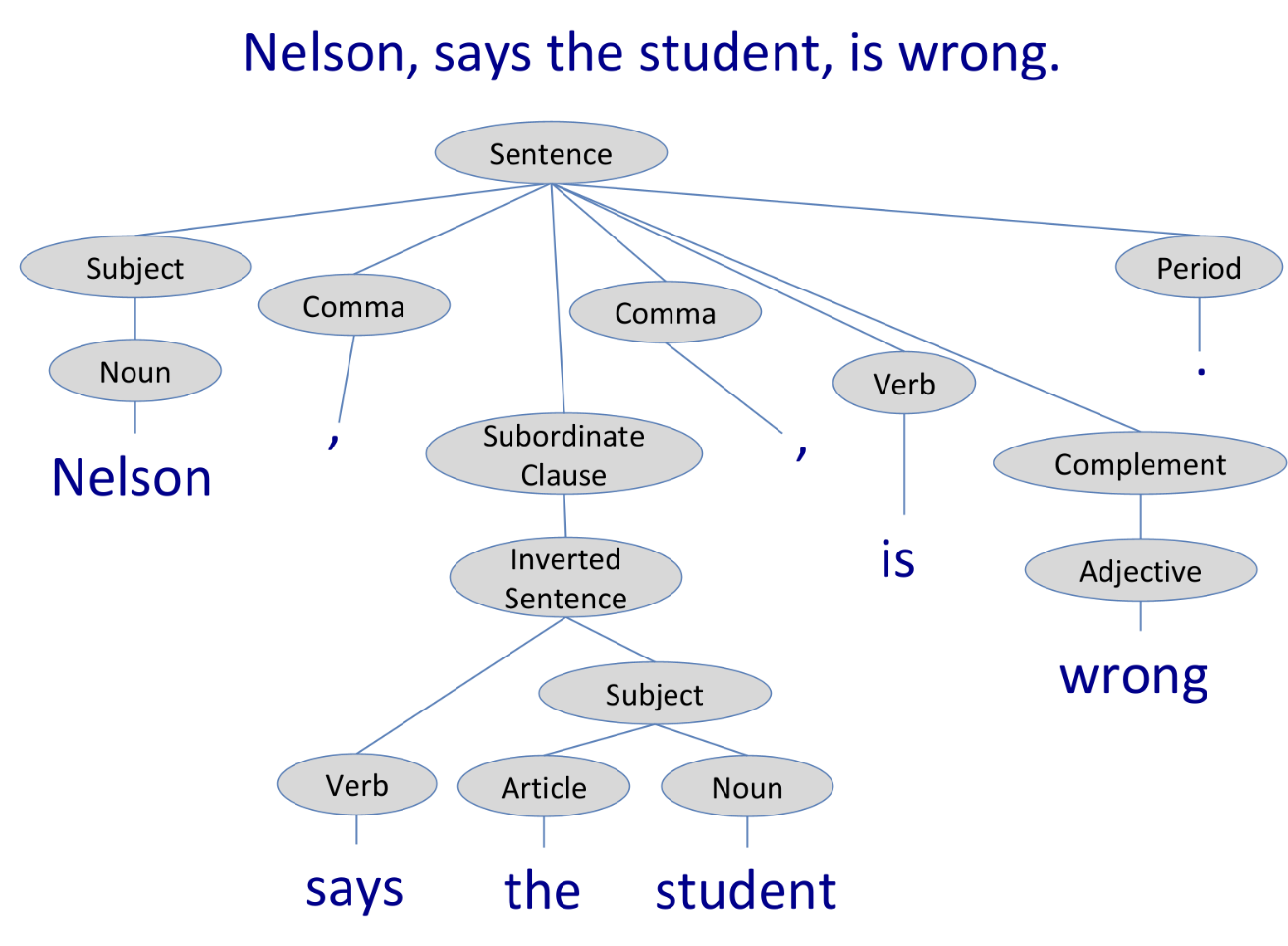

Grammars generate languages, which can be recognized Languages, in all forms, follow a tree structure

In increasing order of generality:

Combinational Logic < Finite-state machines < Pushdown Automaton < Linear-Bounded Automaton < Turing Machine

define all of these

Again, in increase order of generality:

A regular grammar is, broadly, a grammar works like a regular expression. They have no memory of what was generated in the past, and as such can be implemented with a state machine (which is how regular expressions are implemented).

A context-free grammar has no context constraints; it can generate a language without additional context, i.e. knowledge about what has already been seen and what structure the recognizer is "in". It can be implemented with a pushdown automaton.

A context-sensitive grammar needs context to generate a language. We can think of this adding "states" to a parser; the parser may choose to match to different expressions based on the state, and the state can be changed by recognizing a rule. They can be implemented with linear-bounded automata.

A recursively-enumerable grammar/language can only be recognized by a Turing machine. If a given input is in the language, it will be accepted by the Turing machine. Otherwise, the input is rejected, or the machine loops forever.

ANTLR lets you define context-sensitive grammars with -> pushMode(my_state), which we can use to push a new state onto a context stack. Then, we can define rules under a mode my_state: statement to bind them to the particular state.

-> broadly means that the evaluating the rule produces a side-effect.Extra reading: Formal language theory: refining the Chomsky hierarchy.

Kids make bad hamburgers

A sentence is ambiguous if it can be validly parsed into more than one semantically different trees.

i * j could mean the expression "i times j", or "j is a pointer of type i"; this comes from the fact that * has multiple different meanings.A language is ambiguous if it contains at least one ambiguous sentence, i.e. a grammar is ambiguous if it contains a sentence that can be built into two distinct parse trees.

As mentioned previously, ANTLR will try to match rules in order. Thus, if a grammar is ambiguous, ANTLR will pick the interpretation that is listed first.

Ambiguity forces the lexer to pick between principles: match the longest possible string, or traverse the language without backtracking? This is a design decision; ANTLR chose the latter option.

check correctness?

Both of these read input from left to right, but differ in how they attempt to match the input.

An LL parser explores the leftmost derivation of the rule it is examining. In that sense, it is top-down: it starts with a rule (namely, the first one) in mind and tries to match to other rules as it goes. So, it is goal-oriented.

LL Parsers are also called descent parsers because they start at the top of the tree.

In contrast, an LR parser will consume tokens until it finds a complete sentence that it can match the accumulated tokens to, i.e. it builds the parse tree from the bottom up. It must find the rightmost character before it can match to a rule; it takes the rightmost derivation.

We can characterize parsers with the following attributes

descent | ascent, i.e. top-down vs. bottom-uprecursive | not recursiveANTLR generates LL(*) recursive descent parsers by default. However, we can bend its output to our will, e.g. by declaring <assoc=right> before a rule to force ANTLR to parse it from the right (correctness).

But what is ANTLR?

A left-recursive rule is a rule of the form \(\text{r} \to \text{r} \, X\); the leftmost entry in the rule is a recursive call to that rule itself. This causes infinite loops in recursive descent parsers, since they descend the leftmost recursive expression first every time and never get to the "base case", if one exists.

E.g. a recursive descent parser generator may produce the following code

// RULE:

// r: r X

void r() {

r();

match(X);

}

// clearly, we never reach match(X)If operations involved in a rule are commutative, we can "switch" the order of the nodes; we write the non-recursive rule first. E.g. since \(+\) is commutative on \(\mathbb{Z}\times \mathbb{Z}\), the two expr definitions are equivalent:

// left-recursive

expr : expr "+" INT | INT;

// not left-recursive

expr : INT "+" expr | INT;However, if we have some operation that isn't commutative (or worse, also isn't associative), fixing the problem is not as trivial. But even if it were, we usually want to do more than simply recognize a language; we want to parse, which requires more structure.

It figures that sometimes, describing a grammar with left-recursion makes sense. Thus, the parser must adapt.

ANTLR 4 allows for direct left-recursion, i.e. it allows grammars like

expr

: expr '+' expr

| ...

| INT;This is done by rewriting recursive rules.

We can translate concepts in the grammar to constructs into constructs in the OOP paradigm. The entire parser is encapsulated into a class, which holds everything that affects the current state of the parser i.e. current token, lookahead token(s), input stream, etc.

public class G extends Parser {

// token INT type definitions

// constructors as needed

// methods for rules

}Each grammar rule \(r\) becomes a method public void r() in the parser class

begin-type sequence of corresponding function callsmatch(T) call in the function of the rule that called itEach token \(T\) is mapped to a unique integer public static final int T

INVALID_TOKEN = 0 mapping to an invalid token, and EOF = -1 to denote the end of the fileSince our parser is LL, we must try to match alternatives. This is done by iterating through all the possible matches (i.e. that layer of the tree), looking at the current token (and possibly lookahead), and matching to the first correct option.

Single-token lookahead can be implemented with a switch statement, since we can just switch based on the value of the lookahead token directly.

Optional (T?): we attempt to match as per usual, but if we don't match to anything, we don't throw an exception (or do anything).

One or more (T+): we use a do-while loop instead of an if-statement for that particular clause

Zero or more (T*): we use a while loop instead of an if-statement.

A non-greedy rule is (roughly) a rule that can be stopped by something. E.g. LINE_COMMENT: '//' .* would consume everything in the file after the comment; we want it to stop when it sees \n. We can specify LINE_COMMENT: '//' .*? '\n' to do just that.

.*, but it will check each time if the current token instantiating . is \n. If so, it will match the '\n' in the rule instead.'/*' .*? '*/'We define two types of lookahead sets:

Point of disambiguation: an alternative is an "or" clause in a rule; e.g. a stmt can be an if or a while or a for etc.

The FIRST set for a given alternative is (generally?) the set of tokens needed to uniquely identify that particular alternative when the parser is looking at the rule it's part of.

E.g.

stmt

: 'if' // lookahead: { if }

| 'while' // lookahead: { while }

| 'for' // lookahead: { for }

;

body_element

: stmt // lookahead: { if, while, for }

| LABEL ';' // lookahead: { LABEL } (we don't need ';' since "LABEL" already gives us everything we need to know to know which alternative to pick)

;The FOLLOW set defines which tokens (possible just terminals? check) that could possibly appear after an alternative in a rule. We need it when the FIRST set includes every node in the rule and still doesn't provide enough information.

A rule may be an empty alternative, i.e. one of the alternatives to the rule is \(\varepsilon\), which represents a "nothing" and ultimately gets translated into the empty string.

To determine the follow set, we need to be aware of the rest of the grammar.

A parser is non-deterministic over a particular rule in a grammar if the lookahead tokens do not uniquely determine the rule's alternatives.

E.g. An LL(1) parser is non-deterministic on expr : ID '++' | ID '--'; because it can only look ahead by one token, and thus can only see ID. In contrast, an LL(2) parser is not non-deterministic over expr because it can look ahead far enough to distinguish the alternatives using '++' and '--'.

expr is LL(2).We can left-factor a rule by consolidating different cases with the same prefix into a single logically equivalent case with that prefix and a grouped set of alternatives:

expr : ID '++' | ID '--';

// vs.

expr : ID ('++'|'--');This reduces non-determinism by reducing the number of rules; the delegation into "alternatives" is deferred to the next recursive level, i.e. when the members of the rule are matched.

Some left factoring rewrite rules

r : A B | A C --> r : A (B|C)

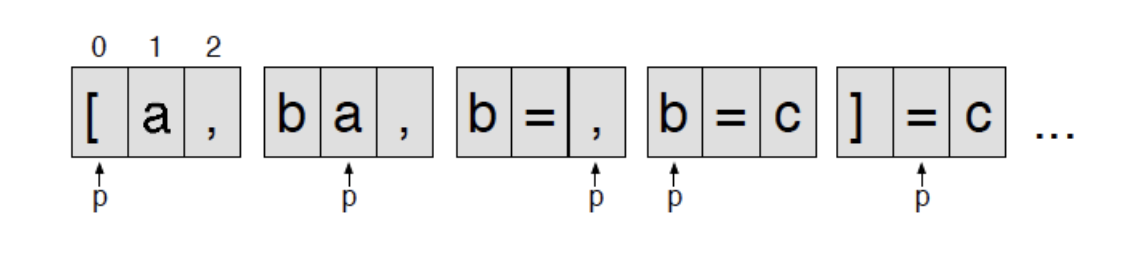

r : A | A B --> r : A (B)?We build an LL(k) Recursive-Descent Parser in Java; its goal is to parse nested lists in the form [a, b, [c, d], e …]

public abstract class Parser() {

Lexer input;

Token[] lookahead;

int k; // lookahead symbol count, i.e. size of buffer

int p = 0; // next position to fill in circular buffer

public Parser(Lexer input, int k) {

this.input = input; this.k = k;

// create lookahead buffer

lookahead = new Token[k];

// fill up the circular buffer

for (int i = 1; i <= k; i++) consume();

}

public void consume() {

lookahead[p] = input.nextToken();

// get the next circular buffer address with mod operator

p = (p+1) % k;

}

// fetch next token from circular buffer

// LT: load token

public Token LT(int i) {

return lookahead[(p+i-1) % k]

}

// get type of next token (needed for matching non-literal tokens)

public int LA(int i) {

return LT(i).type;

}

// match function

public void match(int x) {

if(LA(1) == x) consume();

else throw error("Expecting " + input.getTokenName(x) + "; found " + LT(1));

}

}This extends the parser by adding methods for the specific grammar rules.

public class LookaheadParser extends Parser {

pubic LookaheadParser(Lexer input, int k) {

super(input, k);

}

// match to '[' elements ']'

public void list() {

match(LookaheadLexer.L_BRACKET);

elements();

match(LookaheadLexer.R_BRACKET);

}

// match to INT, ..., INT

void elements() {

element();

while(LA(1) == LookaheadLexer.COMMA) {

match(LookaheadLexer.COMMA);

element();

}

}

// etc

}Just in case you forgot how "public static void main string args" works

public class Test {

public static void main(String[] args) {

ListLexer lexer = new ListLexer(args[0]);

ListParser parser = new ListParser(lexer);

// begin parsing at the "top level" rule

parser.list();

}

}LL(k) parsers need lookahead. Sometimes, a lot of lookahead. We must buffer the token stream in order to handle this lookahead efficiently.

We can use a circular buffer for this task. Each time we read the next token, the previous one is replaced with the newest token that isn't in the buffer already. Thus, the input "snakes around" the buffer.

In some cases, a language cannot be parsed by an LL(k) parser, for some fixed \(k\in \mathbb{N}\), namely the first rule of a grammar starts with a star pattern, and thus can match to any number of tokens/rules.

Right now, the program doesn't really output anything; it just parses the input, i.e. makes sure it's valid according to the grammar. Later, we will see that we can include implementation language (here, Java) code in the grammar directly. It's this code that will get run as part of the rule methods and produce a meaningful result.

A search algorithm will discover nodes in its discovery order. E.g. DFS on the tree (+ (a) (b)) has discovery order + a + b +. Note how the discovery includes passing back through parent nodes.

Relatedly, a traversal of a graph is the order in which its nodes are first visited. Trees, in particular, are amenable to certain traversals (wording, this sucks)

+ a ba + ba b +We can see that traversals are characterized by the order of visiting the two children and parent, so there are \(3!=6\) traversals of binary trees. However, the location of the parent is usually the most important; if we fix that the left child must come before right, we get the list above.

A mixed traversal may include preorder, in-order, and postorder actions; these are inserted before, between, and after the visitations of child nodes, respectively.

Aside: in my opinion these terms should be switched: discovery should happen only once, whereas visiting could happen more than once. Real Iceland/Greenland situation here. prankd.

We visit the parse tree by defining a walk() function on each node. Generally, this function will perform something related to the function of the current node and call walk() on its children, if present.

The implementation of walk() defines how we traverse the tree.

Note that mixed traversal is useful for parse trees, e.g. parsing an AST into a LISP-style s-expression:

void walk() {

// preorder actions go here

// note: for LISP printing in particular, checking if we're not in a leaf

// lets us avoid printing every integer literal, etc. in ()

print("(");

print(curNode.operator);

left.walk();

// in-order actions go here

right.walk();

// post-order actions go here

print("(");

}Listeners and visitors are both patterns for traversing trees with data. In the context of parse trees, these patterns provide a way to implement the "next step", e.g. evaluating the program directly (an interpreter) or translating it into another language (a compiler).

These patterns create a layer of abstraction between the grammar and this "next step"; they decouple the grammar itself from the application code. Thus:

More on this software engineering later.

A visitor pattern involves defining a visit() method for each type of node in the tree. The traversal is implicitly defined by the visit() function implementation; visit() should be called recursively on the children of the current node. The traversal is initiated by calling visit() on the root node of the parse tree.

Results are returned from child visitor methods to be used in the parent visitor method.

A listener pattern involves defining an enterNodeType and exitNodeType method for each type of node in the tree. When a node is first visited, its corresponding enter function is called; when all its children have been visited and we are done with that node, we call its exit method.

Generally, using a listener (and, even more generally, traversing with DFS) requires the use of a stack to handle things like expression parsing (more on this in V0C).

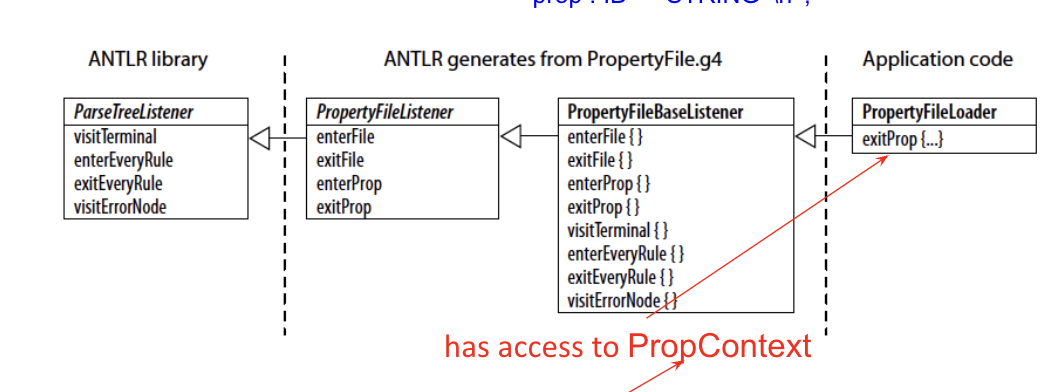

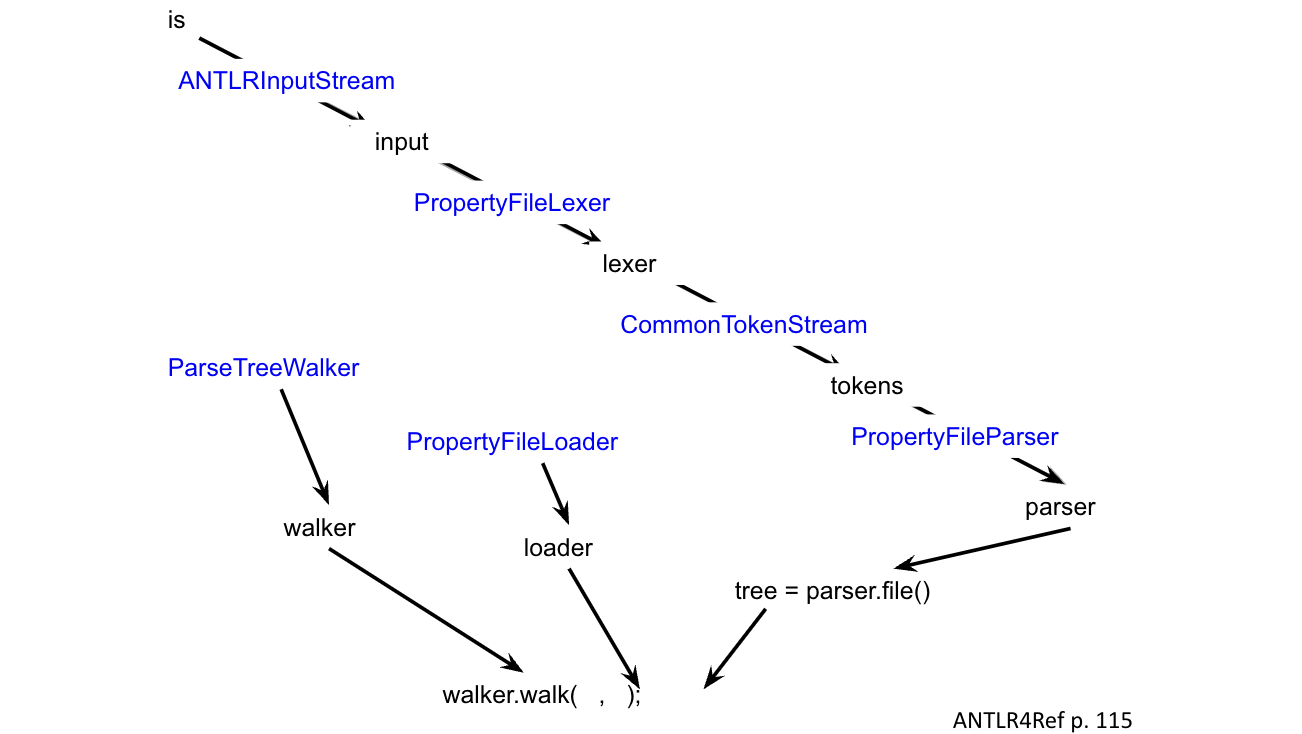

We can use ANTLR to generate templates for visitors and listeners for a given grammar. Specifically, ANTLR generates a base listener/visitor class that defines all the visit/(exit, enter) functions. Your listener/visitor should inherit from the base and override these function definitions.

Refactoring guru: visitor pattern and listener/observer pattern

We decouple the grammar from the application code by using the visitor and listener patterns, as covered in V09.

We can (ANTLR3?) embed actions in the grammar; this lets use do the "next step" directly in the grammar, as the input is being lexed and parsed. In ANTLR, we can add actions to the grammar with {} syntax.

grammar exprs;

exprs = {

// Java code here

// start handling exprs (i.e. enterExprs)

// note: we can access nodes in the rule with $ID if ID is in the rule, etc.

} expr+ {

// Java code here

// exitExprs

};

ID : [a-z]+;

//etc.A preliminary way to decouple the grammar is to only call output-agnostic functions in the embedded Java code, e.g. handleExprs(), instead of embedding the code directly. This lets us handle multiple languages, i.e. we can have different (polymorphic) implementations of handleExprs() for an interpreter, compiler to C, compiler to RISC-V, etc.

As mentioned previously, we can generate a listener or visitor that does a completely separate walk over the parse tree. Then, to define a "next level", we inherit from the base visitor/listener and override-implement all the functions.

ANTLR also defines a maximally general ParseTreeListener class, which implements methods that work on any parse tree: visitTerminal, enterEveryRule, exitEveryRule, visitErrorNode.

The full ANTLR class structure is as follows:

Code for all of this is in the V0A slides; might transcribe it here later.

Say we have a large rule with lots of alternatives (expr being a canonical example). Each time we enter, exit, or visit an instance of that rule, we have to reach into the context (i.e. the ParseTreeContext ctx parameter in ANTLR-generated visitors/listeners) to figure out which alternative (here, which operator) we picked.

In ANTLR, we can add labels to alternatives. This directs ANTLR to generate specific enter/exit/visit methods for each label, instead of for the rule in general.

We define the expr rule:

expr

: expr op=MULT expr #Multiplication

| expr op=ADD expr #Addition

| //... #...

| INT #IntegerExpr

;With a visitor, this generates visitMultiplication, visitAddition, etc. methods instead of a single visitExpr method. Analogous methods are generated for a listener.

more code in the slides → transcribe later

event methods?? and why can't they pass information around?

does a regular visit/listen method still get generated, or just the alternatives?

In an event method, we might want to pass values down into the children or up into the parent. However, we can't define our own parameters because they change the signatures of the generated event methods. What do?

enter/exit/visit method corresponding to some rule in a grammar.We have 3 main methods of sharing information among methods

visitWe may simply return the value we need when we are done visiting a rule. E.g. visiting an expression that adds two integers returns the resulting integer.

(*) In ANTLR's generated C++ visitor methods have return type std::Any. Thus, we return a result of any type we want and use an any cast (std::any_cast<target_type>(visitor_result)) to retrieve that result in the parent.

In the stack method for listener value passing, we simply keep a stack in the main object, which is accessible to all the event methods. When we enter a terminal value that we'll need, we push it to the stack. Then, when exiting the rule, we pop the arguments we need off the top of the stack, use them to product any return values we need, and push those to the stack.

This is also space efficient (since no data is attached to the tree), with the added advantage that multiple expressions can be passed and returned (!) with each event method. However, the implementor is responsible for managing the stack manually, which gives them enough rope to hang themself with.

Instead of storing intermediate data on The Stack, we can store it on the tree itself with annotations. Essentially, we walk through the tree and annotate a node with its corresponding intermediate value. Working through the tree bottom-up, we eventually arrive at the root note with the full result we need.

Values : ParseTreeNode -> Value to store and retrieve from.ParseTreeProperty<Integer>; ANTLR makes this type for us to enable use to use this methodclass InterpreterWithProps extends ExprBaseListener {

// node -> value map

ParseTreeProperty<Integer> values = new ParseTreeProperty<Integer>();

// ...

// IN A METHOD

// annotating a node

values.put(cur_node, cur_value);

// retrieving a value from a node

values.get(cur_node)

}Parse tree annotation lets us provide arbitrary information because any method in a listener or visitor can access the map whenever it wants, and thus can access information about other nodes in the tree.

However, the source code is less intuitive and more space than necessary is used, since nodes and values are getting copied to an external data structure that stores partial results for the entire lifetime of the program.

A we can specify a return value in the grammar itself with the returns keyword

expr returns [int value]

: expr MULT expr

| expr ADD expr

;int value must be using the syntax of the target language, in this case Java → less decouplingThis value will be visible as a field in the ParseRuleContext type object directly (specifically, in the subclass corresponding to the current rule, in this case ExprRuleContext). All methods that use an expr will have access to this value.

public ... ExprRuleContext extends ParserRuleContext {

public int value;

//...

}the following lecture topic involves writing a Calculator interpreter using a visitor, and a Translator using a listener, both in Java

if you're reading this, I didn't make notes on it because a) it mostly summarizes/applies things we've already covered and b) later material is more urgently needed for my midterm prep

exhaustive list of actions, I feel like there were some in previous slides, no?

If we feel insecure about our OOP knowledge and want to avoid inheritance wish to forgo visitors and listeners, we can use actions to include application code in the grammar directly.

The @parser::members action adds members to the MyGrammarParser class that gets generated automatically; we may use these members later in the grammar using {} syntax to drop into our application programming language (e.g. Java).

localsIn this example, we parse tab \t separated lists; we want to be able to pass in a column number n to the parser and print only entries in that are in column number n.

grammar Rows;

@parser::members {

// in here: Java

// adds a col member to the RowsParser object

int col;

// we must redefine the constructor to initialize this new field

public RowsParser(TokenStream input, int col) {

this(input);

this.col = col;

}

}

// back to the grammar

file: (row NL)+;

// rule for "row" in the grammar

// we define a local variable i with locals (Java in the [])

row locals [int i = 0;] : ( /* grammar nodes etc */ STUFF {

// in here: Java

// we access local parameters we've defined earlier

// and grammar nodes with $ syntax

$i++;

if($i == col) System.out.println($STUFF.text);

})+ ;

// skip whitespace, etc.Then, in the main function where we build our parser, we call the RowsParser constructor. We do not build a tree because the output is generated while the grammar is being parsed; we just call the root rule in the parser object.

public class Col {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

// set up the ANTLRInputStream, RowsLexer, CommonTokenStream as per usual

// ...

int col = 0; // read from args or whatever

// constructor, with the col value as specified earlier

RowsParser parser = new RowsParser(tokens, col);

// we will NOT build the tree

parser.setBuildParseTree(false);

// instead, we parse the root rule, in this case file

parser.file();

}

}Aside: does being able to pass arguments in like this affect the \(k\) parameter of the parser and/or whether it's context-free/sensitive?

Semantic predicates and their consequences have been a disaster for the human race

Problem statement: we want to parse a file with the following format; we want to parse the input into a list of groups.

Here, the structure of the parse tree depends on previous values that have been parsed.

We can implement this grammar with a semantic predicate, which is an alternative predicated on one of the values in the rule itself. It uses the {} syntax to access the implementation language, and passes a parameter into the sequence rule with [] syntax.

i to keep track of how many integers we have read into the group. If we still have space left in the group (i.e. if \(i < n\)), then the semantic predicate keeps the alternative visible. Otherwise, once we've read everything, the alternative cannot be taken anymore.grammar Data;

file: group+;

// we pass the integer value of the first token into the sequence rule

group: INT sequence[$INT.int];

// sequence rule

sequence[int n]

locals [int i = 1;] :

// match n integers

// i.e. if we haven't matched n integers yet (which we keep track of with i)

// continue to make this rule available here

// and since it's the first one, we will keep taking it

({$i <= $n}? INT {$i++;})* ;

// tokens ...Generally, we don't need semantic predicates, so they should be regarded like many obscure features of programming languages: if you're using it, you're probably using bad style (and should do something else) or you've structured something wrong up the chain. However, for pathological grammars, semantic predicates can clean up the specification.

An island grammar contains grammars for multiple languages in the same file. To support this, multiple lexer modes are defined; a particular rule (a sentinel character sequence) tells the lexer to switch modes and start parsing a different language.

E.g. for an XML parser, < tells the lexer to switch into "attribute" mode, where it looks for attributes in the header of a tag instead of for other tags inside it

lexer grammar XMLLexer;

// default "mode" starts at the top of the file

OPEN: '<' -> pushMode(INSIDE);

COMMENT: '<!--' .*? '-->' -> skip;

EntityRef: `&` [a-z]+ ';';

TEXT: ~('<'|'&')+; // matches any 16-bit char except '<' and '&'

// the mode for something INSIDE a tag

mode INSIDE;

CLOSE: '>' -> popMode;

SLASH_CLOSE: '/>' -> popMode;

EQUALS: '=';

// etc.Related reading: Chapters 5 (Designing Grammars) and 6 (Exploring some real grammars) of Language Implementation Patterns.

Improve your parsing chops

DOT is a domain specific language for describing graph-theoretic visualizations. In this section we use it as an example for constructing an "actual", pragmatic grammar. A more in-depth description of the language can be found here.

digraph G {

rankdir=LR;

main[shape=box];

// define edges main -> f and f -> g

main->f->g;

// styled edge

f->f[style=dotted]

f->h;

}DISGUSTANG

// tokens

STRICT: [Ss][Tt][Rr][Ii][Cc][Tt];

GRAPH: [Gg][Rr][Aa][Pp][Hh];DOT accepts strings of HTML, which must occur in matched pairs.

<<i>text</i>>, e.g. < appearing in a comment. What's going on?The first naive approach to this is to write a rule like

HTML_STRING: '<' .*? '>';<<i>hi</i>> would include two HTML_STRING tokens <<i> and </i>> (don't worry; tags in angle brackets like this is valid in DOT)

> in the second example is not an error; it is a result of the lexer matching to the longest possible sequence. The non-greedy loop just means that it has to end with a >.We could also try

HTML_STRING: '<' (TAG | .)*? '>';

TAG: '<' .*? '>';<i and /i> can be matched by ., i.e. when trying to match the longest possible sequence, the lexer sees <<i> as a tag of type <i.To solve this problem, we need to explicitly define that the characters < and > cannot be in the header of a tag, i.e. part of the tag name:

HTML_STRING: '<' (TAG | ~[<>])*? '>';

TAG: '<' .*? '>';Note that implementing HTML_STRING with a recursive call to itself instead of tag would match the case <<i>hi</i>> properly, but would also recognize false positives, e.g. <<i<br>>>.

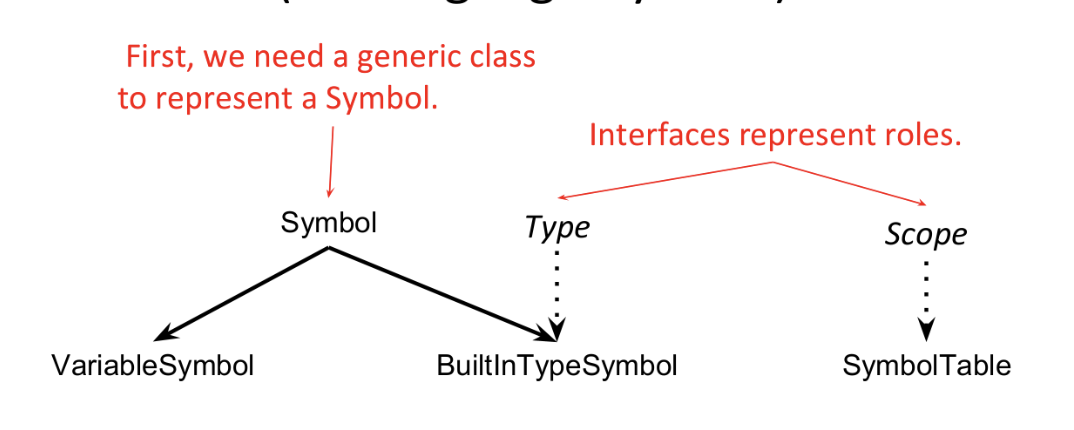

Variables in a program are like characters in a novel Very cool and meaningful takeaway inside: "interfaces are types and types are interfaces"

A symbol or atom in a programming language is a (the) primitive piece of data, whose form is human-readable. A symbol may be an identifier, literal, keyword, etc. A symbol table is a registry of all the current symbols in a program (the language starts with some, and more are added at runtime).

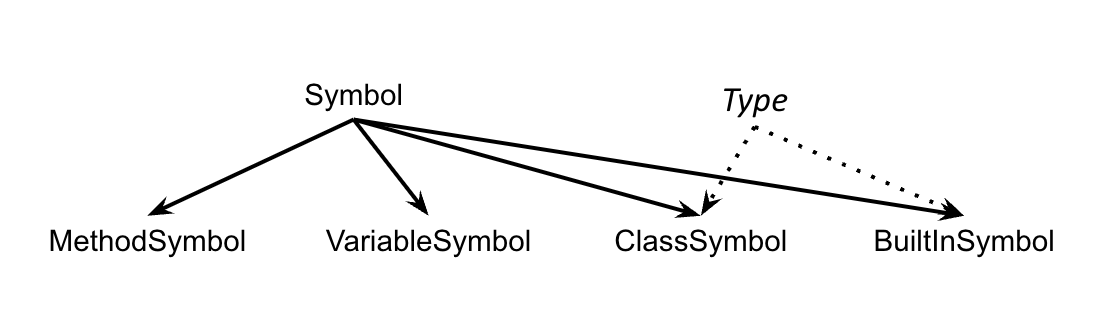

A symbol must have a name, a category, and a type. E.g. the symbol f in the C++ statement T f() {…} has name f, category method and type T.

We can represent a symbol in a program (presumably one that deals with other programs, like an interpreter or compiler) as a class or structure, with each attribute listed above as a field. The type of this value corresponds to the category of the symbol.

// corresponds to "class T{...}"; we define the type T, which can be used later

// note how classT{...} is basically "define type T"

Type t = new ClassSymbol("T"); T{...};

// corresponds to f in "T f() {...}"

MethodSymbol m = new MethodSymbol("f", t);

// create a new built-in-type symbol "int" so we can declare ints

Type intType = new BuiltInTypeSymbol("int");

// correponds to x in "int x;"

VariableSymbol v = new VariableSymbol("x", intType);A implement a symbol table by writing a common superclass for all symbol classes. Then, we can just store an {name, Object} map (or whatever structure) of this.

public class Symbol {

// fields needed for every symbol

public String name;

public Type type;

}User-defined types are represented as interfaces, which act as tags that can be "added on" to program symbols. This interface characterizes user-defined types from other program symbols. Any symbol implementing this interface must be a type.

// a symbol class for a built-in type symbol

public class BuiltInTypeSymbol extends Symbol implements Type {

// ctor

public BuiltInTypeSymbol (String name) {

super(name);

}

}

// Type interface

public interface Type {

public String getName();

}

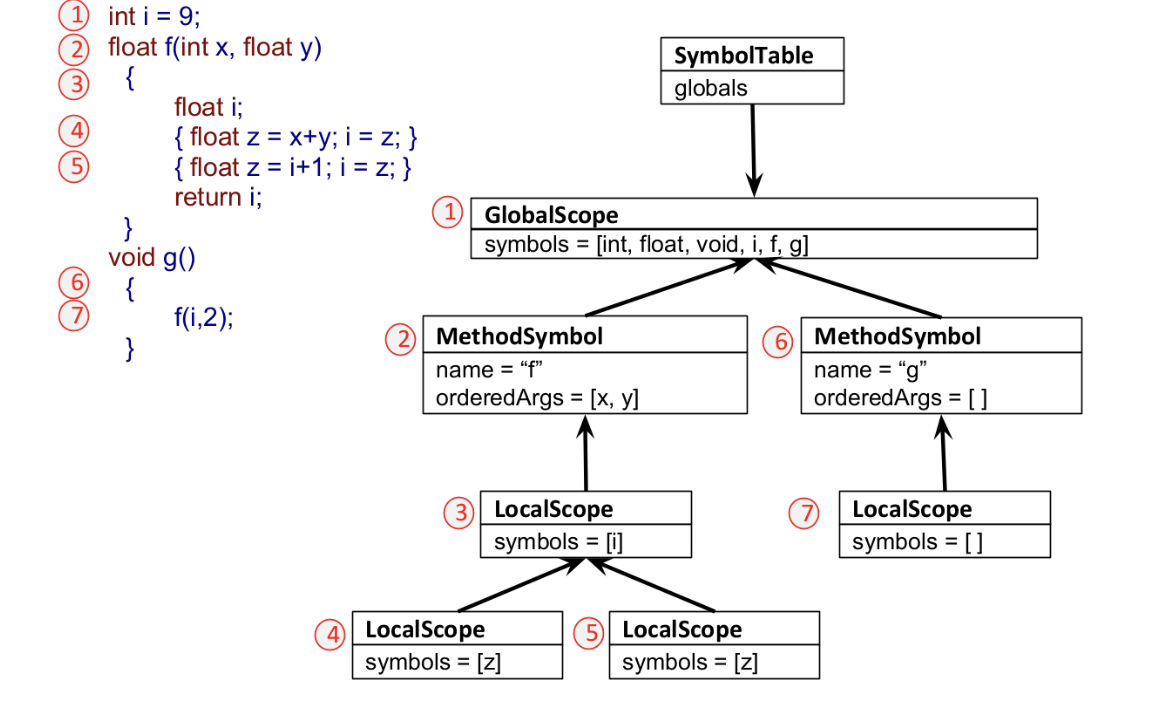

A scope is a well-defined region of code that encloses symbol definitions. A lexical/static scope is a scope that can be known at compile time; usually this means scope explicitly defined by tokens in the source code. A dynamic scope is a scope that can only be known at runtime.

{}, including C, C++, Java, etc.A named scope has a name (e.g. classes, methods, function definitions, etc.); some scopes aren't named (e.g. the global scope/top-level scope of the program). A nested scope is a scope that appears inside another scope; most languages allow this.

The visibility of a scope is defined by the language, and can sometimes be defined in the language directly, i.e. with keywords like public, private, etc.

A language with a monolithic scope has a single global scope for the entire program, e.g. config files. These are best implemented with a map that matches symbol names to Symbol objects.

Like with types, we can define an interface that tags an entity as a scope. Unlike with types, more methods are needed to provide ways to interact with the scope, which we will need.

public interface Scope {

public String getScopeName();

// get the scope surrounding this one (possibly the global scope)

public String getEnclosingScope();

// create a new symbol in the scope

public void define(Symbol sym);

// resolve a name (string) to a symbol in the current scope

public Symbol resolve(String name);

}Monolithic scopes are easy to organize; we just have one. However, multiple (and particularly nested) scopes imply a scope stack or scope tree structure for storing the scopes of a program. More on this later.

should there be more here or do we cover it later?

tree ref and push and pop and stuff?

We resolve a symbol name by retrieving the Symbol object it refers to or determining that it is mapped to no Symbol object at all. This depends on the scope are are currently in, because the same symbol name defined or undefined (or correspond to a different object) depending on the scope.

To resolve a symbol name, we look at the associated Symbol object in the innermost scope. If we can't find it there, we check in the enclosing scope, then that scope's enclosing scope, etc.

Scope interface needs a getEnclosingScope functionnull)public Symbol resolve(String symbol_name) {

// look for the symbol in the current scope

// since a scope is "monolithic within itself" (I guess),

// we use a map to associate names to values within the scope

Symbol s = members.get(name);

if (s != null) return s; // guard stmt

// if we made it here, our scope doesn't define the symbol

// so we recursively resolve the symbol in the enclosing scope

if(enclosingScope != null) {

return enclosingscope.resolve(namne);

}

// if we made it here, the symbol isn't defined anywhere

return null; // or throw an error or something

}for later: what a data aggregate IS is to expose its inner scope through its own namespace

a struct is both a type and a scope, this is what aggregates are

arith result table looks like a group mult table

We define a language Cymbol with the following grammar to illustrate concepts relating to symbols and scoping; its syntax is similar to C, hence the name. We just define the grammar here, we don't put anything (e.g. annotations?) in it.

grammar Cymbol;

// a declaration may include a definition, or not

varDeclaration : type ID ('=' expression)? ';';

// only number types

type: 'float' | 'int';

// expressions

expr: primary_expr ('+' primary_expr)* ;

primary_expr: ID | INT | '(' expr ')';

// tokens

ID: LETTER (LETTER | '0'..'9')*;

fragment

LETTER: [a-zA-Z];

INT: [0-9]+;

// hidden

WS: (' '|'\r'|'\t'|'\n') {$channel=HIDDEN;};

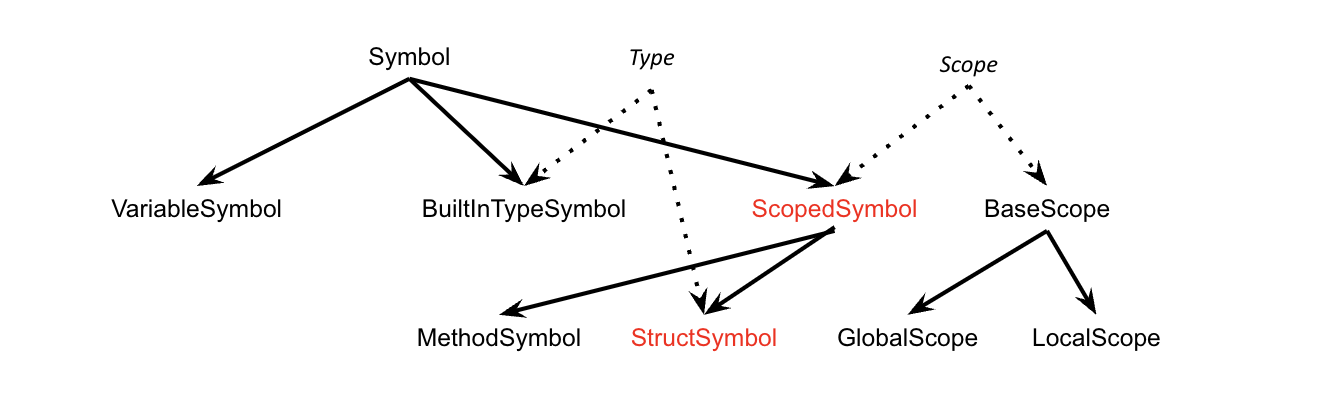

SL_COMMENT: '//' ~('\r'|'\n')* '\r'? '\n' {$channel=HIDDEN;} ;So our resulting classes are organized like this

We can construct a symbol with a name, or with a name and a type; so, the Symbol class has two constructors, once of which has an additional this.type = type; line. We also define getName() and toString() functions.

code in here later

Symbol is extended by two subclasses: VariableSymbol, which simply calls super, and BuiltInTypeSymbol, which implements Type.We create a SymbolTable object as a dictionary to hold the symbols. If this symbol table is monolithic, our scope tree only has a single node, so we can use the symbol table to implement scope as well (correctness?).

import java.util.*;

public class SymbolTable implements Scope {

// data structure to hold the dictionary

Map<String, Symbol> symbols = new HashMap<String, Symbol>();

// ctor

public SymbolTable() { initTypeSystem(); }

// initiate the type system:

// create symbols for built-in types that need to exist immediately

public void initTypeSystem() {

// note: define is a function implemented in this class

define(new BuiltInTypeSymbol("int"));

define(new BuiltInTypeSymbol("float"));

// etc.

}

// symbol table is in the global scope -> nothing enclosing

public String getScopeName() { return "global"; }

public Scope getEnclosingScope() { return null; }

// add a new symbol to the symbol table

public void define(Symbol sym) { symbols.put(sym.name, sym); }

// resolve a symbol (remember, monolithic scope, so no recursion necessary)

public Symbol resolve(String name) { return symbols.get(name); }

// toString()

public String toString() { /* ... */ }

}If we follow the ANTLR3 way of doing this, we will need to access the symbol table in the grammar directly in order to resolve symbols

grammar Cymbol;

@members { SymbolTable sym_tab ;} // remember, this is Java code inside {}

// compilationUnit is the start (root) rule

// we pass the symbol table to it as a parameter

compilationUnit[SymbolTable sym_tab]

// on start up, initialize the symbol table

// aside: does this mean @init places the code in the block into the ctor?

@init { this.sym_tab = sym_tab; }

// now we can define the alternatives for the compilation unit rule

: varDeclaration+ ;

In the type rule, we must resolve the type symbol from the name in the grammar (using the symbol table), then return the specific type symbol (ANTLR has a returns keyword!! also @after is executed just before the block returns)

type returns [Type type_sym]

@after {

System.out.println("line" + $start.getLine() + ": ref" + $type_sym.getName());

}

// syntactic predicate?? check

: 'float' {$type_sym = (Type)sym_tab.resolve("float"); }

| 'int' {$type_sym = (Type)sym_tab.resolve("int"); } ;varDeclaration rules require adding a symbol to the symbol table by calling define. We must use the type_sym that was returned by the Type rule (this would have happened right before).

Then, when we reach an ID (identifier), we resolve it in the symbol table.

The grammar remains clean.

We make a lot of shared pointers shared_ptr in the C++ code. Why? We always declare them when we pass in things (or declare fields) like Type objects. Why shared pointers? Review cpp.

todo: compile the entire grammar into a code file, maybe external

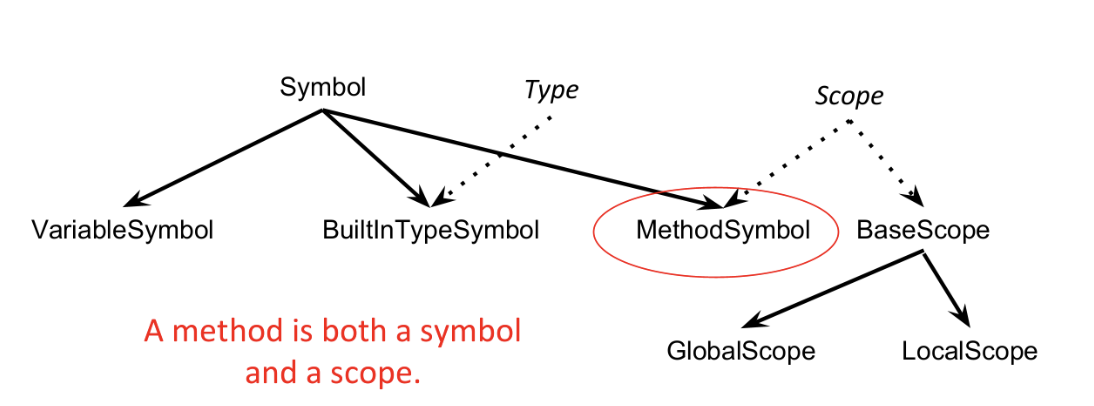

E.g. methods have two scopes: one "outer" scope that includes the parameters of the method, and one "inner" scope that includes the parameters of the method and the local variables defined inside the method. These scopes are nested.

{}, which is a core language feature.

In ANTLR3, our symbol table construction happened in the grammar directly, with annotations? the things with @ being triggered by the grammar rules.

We can also trigger this actions while walking over an AST created from the input source code; this adds an extra pass that allows us to further decouple the grammar from the application code.

In ANTLR4, the idiomatic way to do this is to trigger actions while using a visitor to visit the parse tree.

as we walk along the parse tree or an AST, we interact with the symbol table. We can characterize these interactions in 4 ways:

def: we define something new that requires a new symbol, e.g. method

(def) VAR_DECL, (def) PARAMETER, (def) METHOD_DECLBuiltInType stuff in the global scoperef: we reference a user-defined symbol that's already in the symbol table, e.g. an identifier, a method symbol, etc.

refed → BUT THEY ARE IN LATER SLIDES HUH??????!!push and pop: we push and pop scopes from the scope stack/tree.

BLOCK: it looks like (push) BLOCK (pop)(def) (push) METHOD_DECL (pop) for the scope with parameters, then exactly one level down, (push) BLOCK (pop) for the blockWhen annotating these actions on a AST diagram, the order matters, e.g. we always push before we pop. Things before the AST node text happen before we descend into the tree and things after happen on the way back up; this structure mirrors a listener.

(def) (push) METHOD_DECL (pop)The order is always a subset of (def) (push) NODE_NAME (pop) (ref)

E.g. for a BLOCK rule, we create two rules that match it: enterBlock and exitBlock, both of which are just defined as : BLOCK;. In the enterBlock rule, we define whatever code action we want when entering a block (e.g. pushing, i.e. creating a new local scope) by writing that code directly in the grammar with the {} syntax, then the same on the way out.

tree grammar?

tree grammar DefRef

enterBlock : BLOCK {

// we create a new local scope

// current scope as a parameter so we know what to affix it to

// set this new scope to the current scope

currentScope = new LocalScope(currentScope);

};

exitblock: BLOCK {

// pop the local scope by setting the current scope to its enclosing scope

currentScope = currentScope.getEnclosingScope();

}Since both rules match BLOCK in exactly the same way, we need additional infrstructure to make sure the right one is called. We define block topdown and bottomup rules; each one lists all the rules for "on the way in" and "on the way out" as alternatives, respectively.

topdown: enterBlock | enterMethod | ... ;

bottomUp: exitBlock | exitMethod | ... ;code

when we enter a method, we made a new method symbol (using the return type returned by the Type rule before (?)) Type retType = $type.type_sym; in the current scope, call currentScope.define(our_method_sym) on this new rule, and finally set currentScope = our_method_sym to define the current scope as the method symbol (since the method symbol is a scope).

Then, on exit, we simply set currentScope to its enclosing scope

code

defRef class, visitMETHOD_DECL in our implementation:std::shared_ptr<AST> ty and id for the type symbol and identifier from the parameter t (the AST node representing the method declaration itself); it is the first and second child.getLine()ty and define it as the return type (a shared pointer of type Type)ms with std::make_shared<MethodSymbol>(…) where we pass in id->token->getText() to get the name of the symbol, the return type we just made, and the current scope.currentScope->define(ms) to define the method in the current (global) scopecurrentScope = ms (this is our new current scope)tcurrentScope = currentScope->getEnclosingScope(), which pops the method scopecurrentScope appears to be a field of the parent class, we've been accessing it everywhere

when in doubt, the type is std::shared_ptr<AST>

visitDECL

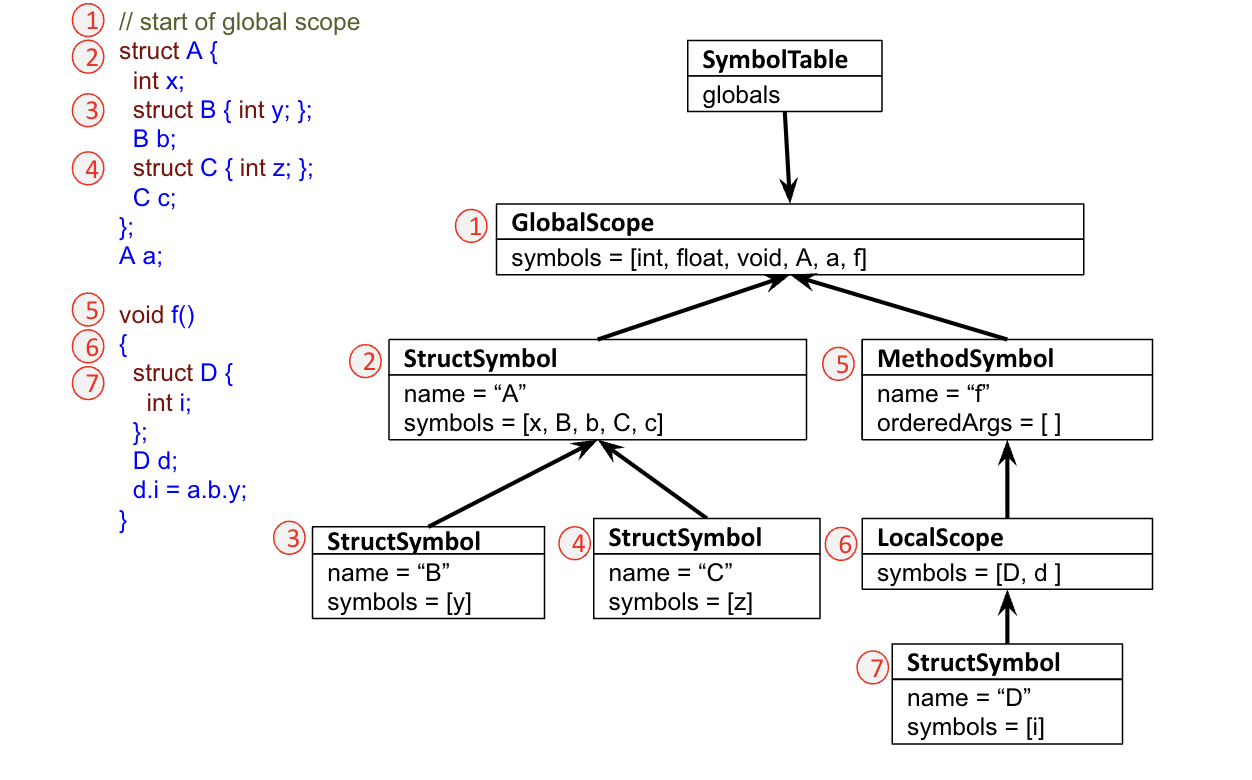

sharedPointer<AST> vars from the parameter to get the type and the id t->children[0], t->children[1]shared_ptr<Type> type = resolveType(ty)vs with std::make_shared<VariableSymbol>(id->token->getText(), type);currentScope->define(vs);t (the input pamater that is an AST node)A data aggregate supports access to multiple fields, e.g. a struct; essentially, a data aggregate encloses its own scope. A class is a type of data aggregate that also allows function definitions within that scope, and may have superclasses as well.

Struct B {int y}; B b; adds symbols B and y, but also b. Things defined with BLOCK i.e {} are of type LocalScopeWhen resolving struct symbols, we cannot walk up the tree! This could cause us to resolve to the wrong variable. Instead, we should find the expression in the scope of the structure, or return "no such field" indicating an error.

resolve for base references and resolveMember for members.Before looking in the global scope, we must look up the inheritance chain. So, if a symbol is not defined within the scope of a class, we look to see if it's defined in the scope of the parent class. The ability to do this is what fundamentally differentiates classes from structs.

diagram from slides?

A forward reference involves defining a variable before declaring it. They are used to tell the compiler that a variable will exist (and thus it can be referenced), but just hasn't been defined yet.

void main() { x = 10; } /* maybe some more code */ int x;We can implement forward references by running two passes through the AST: one for defining symbols, then one for resolving them.

Forward references are not allowed in cymbol outside of a class. We can detect illegal forward references by examining what they resolve to in the resolution pass. E.g. in cymbol, if the forward reference resolves to a local or global symbol, it's illegal, but if it resolves to a field in the same class, it's fine.

ScopedSymbol is an abstract ish class: it is used to categorize the types of scoped symbolss, i.e. MethodSymbols and StructSymbols. We need to differentiate these because only StructSymbols can be types; structs are types, but methods are not.Aside: we use an optional rule for defining member int he grammar

^('.' member ID) (^ indicates an AST construction rule).

Aside: just how in lisp we can implement structs (and local scopes in general) with lambda functions (and vice versa), can we simply desugar all data aggregates to methods if we want?

We store information in the AST nodes: the resolve pass needs the current scope computed in the first pass, so we store that in the corresponding AST node.

Variable declaration int x; in the main method of a class

(def) x as a variable symbol (object, sym) in the current scopeset the sym.def to the AST node of xset the ID AST node's symbol to symset the scope field of x's return type AST node to the current scopeset the scope of x to the current scopemultipel passes:

downupRef ref= new Refwe need to figure out the result types given the input tupes

create type indexes as public static final int tTYPENAME = n for ascending \(n\in \mathbb{N}\)

Create a result table where we can look up the result of type promotions

type computation: look at the AST, get eval types (get the index as an int), look up the result in the table, call propmoteTypeType from the on the type to the result (if its null it just ignores so we can always call it)

where do we need to promote

semantic predicates have syntax {}? and start at the front, if its true the alternative is there, false its not

lexer predicates (are these synytactic prediactes?) are for lexer rules and appear at the end of the lexer rules. They only create the token if the thing is true. Still {}? synatx.

A DFA is genreated

ANTLR 4: for pathological stuff, we just check if the ID is whatever as a parser rule with alternatives: id: 'if' | 'for | ... keywords | ID, then ID token is parsed as normal. ANTLR4 makes this work!

Non-deterministic rule → deterministic rule: semantic predicates!

syntactic predicate vs. LL* uses a DFA not a pushdown and cannot regonzie mathcing parnetihtses? examines future inpout symbols for a rule

sematnic prediates for specifying which ambiguous alternatieve to pick. ANTLR 4 does't need this because its LL star

An operation must be defined for the types of its operands

Different operators impose different type requirements

. requires the left operand to be a structif(expr) block operator requires expr to be of a boolean type= (in lh_val = rh_val) requires lh_val to be an l-value and that lh_val and rh_val are the same type (or are promotable to the same type)We can define a result table/type table where we can lookup the resulting type based on the type of the operands. We also define a type promotion table to lookup what type promotion we should define, given the two operand types.

typeTable[tChar][tInt]Since this kind of type checking is static, we can implement it as an AST pass. Thus, our lookup function is performed on two ASTs:

public Type getResultType(AST a, AST b) {

// get the type indices of the operands

int t_a = a.evalType.getTypeIndex();

int t_b = b.evalType.getTypeIndex();

// look up the resulting type from the table

// typeTable is a static member of the overarching class

Type result = typeTable[t_a][t_b];

// if there is no entry, then something has gone wrong -> error

if(result == t_void) {

// throw error

// bleh

}

// since an entry exists, we lookup the type promotions

// note: if no promotion is necessary, the lookup just returns

// the original value

// so, as a point of SWE, we just always perform the lookup

a.promoteToType = promoteFromTo[t_a][t_b];

b.promoteToType = promoteFromTo[t_b][t_a];

// return the resulting type

return result;

}Under the model of polymorphism, an object may have multiple types, corresponding the members of the leaf → root path of the inheritance tree.

We are allowed to assign an subclass object to a superclass object, but not a superclass object to a subclass object.

So, when doing polymorphic type checking, we must check whether the classes are the same. If they aren't, we must check if the l-value is a superclass of the r-value.

Animal *animal_1, *animal_2;

Dog* my_dog;

Cat* my_cat;

// Example assignments

animal_1 = animal_2; // fine: both are Animal

animal_2 = my_dog; // fine: Dog is a subclass of Animal

animal_2 = my_cat; // illegal: Animal might not be a Cat

my_dog = my_cat; // illegal: Dog is definitely not a CatWe define a canAssignTo function (analogous to the getResultType function earlier) to check whether a polymorphic assignment can happen.

more in the slides: instanceof, etc

This is more less enough to implement type checking for pointers. If the pointer points to a value (e.g. an int), then we check the type table / promotion table. Otherwise, if the pointers are to objects, we perform the polymorphic type checking.

Uh oh

If we are allowed to mutate pointers like values themselves, we must add them as indices in our type table. By definition, if we implement pointer arithmetic, we can operate on pointers with integers, for example.

Static type checking happens in 3 parts correctness

Recall: a semantic predicate lets us "block" an alternative in a grammar rule by computing a boolean expression based on information available at parse-time.

Can be used to extend existing grammars to support multiple versions. E.g. if we have a Java 4 grammar and want a Java 5 grammar, we can couple them and simply have a boolean variable that indicates which version we are parsing against. Then, certain alternatives can be blocked via a semantic predicate if they are not part of that version.

rule : {bool_expr}? alternative_1 | alternative_2We can also define lexer predicates that do the same thing, but in the lexer instead. In this case, the predicate is placed at the end of the lexer rule.

TOKEN : /* pattern */ {boolExpr}?Use case: using keywords as variables

identifier parse rule that looks something like id : 'keyword1' | 'keyword2' | ID, where ID is our identifier token from the lexer. ANTLR4 knows to look for the keyword uses first.Use case: different uses for same token

( being used for grouping and for function calls[…] being used for array access and method calls (Ruby)

A[1] might be access index 1 of array A, or a call to method A with single argument 1. We simply can't know without more context; we need a semantic predicate to provide this context by checking whether A is an array or not. So, the parse rules arrayIndex and methodCall will have a semantic predicate to check.A syntactic predicate examines future input symbols in the token stream; it lets us parse different based on what comes after the current token.

A semantic predicate lets us define a "mini-rule" that ANTLR will try to match to first. If it matches successfully, we choose that alternative. Otherwise, we ignore it.

s : (expr '%') => expr '%' | expr '!'. Here, expr '%' is the mini-expression we try to match to.We can specify auto-backtracking as an option; this tells ANTLR to insert syntactic predicates on the left edge of every alternative. This gets invoked when ambiguity arises.

grammar x;

options {backtrack=true;}A semantic predicate lets us test any (programmer-defined) expression we want; we can access global state and provide additional context about what we are parsing.

What if a sentence just doesn't match the grammar?

Examples of common errors:

(…)+ was exited earlyA basic block of a program is a contiguous region of the program's instructions such that

A program can be partitioned into basic blocks.

So, we know that if one statement in the basic block is executed, then all of the statements in the basic block will be executed as well. This makes basic blocks the atomic "unit" with which to construct larger program structures.

Note: it is common for basic blocks to be only one instruction of the program.

Note: each control flow structure is characterized by the structure of the basic blocks it forms. E.g. if statements have \(2\) basic blocks: the block that computes the condition, and the block that runs if it is true. if-else statements have \(3\). Loops have more, but vary depending on implementation.

Aside: in many languages, blocks (not basic blocks) are delimited with {} or similar. These operate at a higher level than basic blocks, but follow a similar idea (blocks are basic blocks of basic blocks).

A control flow graph is a directed multigraph \(G\) where

So, any possible execution of the program corresponds to a start → end path through the CFG.

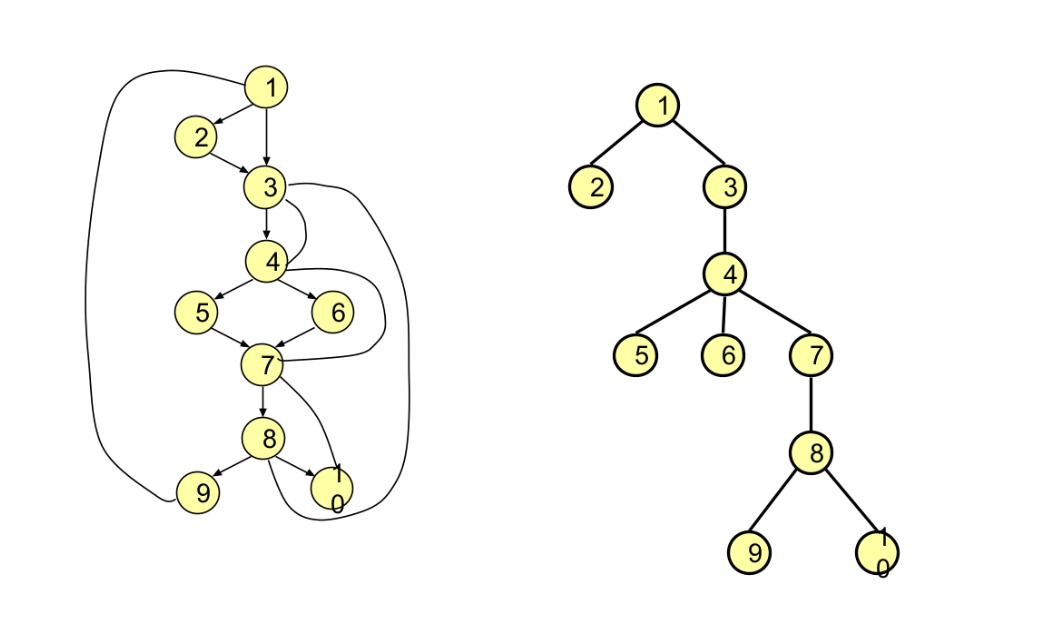

A flow graph \(G\) is a multigraph with node-set \(V(G)\), edge-set \(E(G)\), and a starting node \(s\in V(G)\). For \(a, b\in V(G)\), we say \(a\) dominates \(b\) if and only if every path from \(s\) to \(b\) travels through \(a\).

A dominator tree \(T_G\) of graph \(G\) is a subtree of \(G\) with root \(s\). If node \(a\) dominates node \(b\) in \(G\), then \(b\) is a descendant of \(a\) in \(T_G\).

own example

Heuristically, programs spend most of their execution time in loops, so optimizing loops has a higher payoff, and is thus worth spending more time on. So, it makes sense to develop a way to locate loops in a program independently of the syntax used to declare then (e.g. for vs. while vs. goto, etc.).

A strongly-connected component of graph \(G\) is a subgraph \(G'\) of \(G\) such that a path exists between any two nodes in \(G'\) (thus, these partition \(G\)). A loop is a strongly connected component \(G'_\ell\) such that the starting node \(s_\ell\) of \(G'_\ell\) dominates all the nodes of \(G'_\ell\).

A back edge is an edge \((b, a)\in V(G)\) such that \(a\) dominates \(b\) in \(G\). The existence of a back edge implies a loop with the back edge in it.

example (homework?)

A region \(R\) of \(G\) is is a subset of \(V(G)\) including a start node where

A single-entry-single-exit (SESE) region has a single entry and single exit, i.e. the entry dominates the region and the exit post-dominates the region.

A loop is a type of region where the region is also a strongly-connected component of \(G\). So, loops can only have one entry, but they may have multiple exits.

A point in a basic block is a location in the program that is between two statements, before the first statement, or after the last statement. A path is a sequence of points corresponding to a (graph-theoretic) path through the CFG.

In data flow analysis, we track how values are defined and used at different points of the program. This lets us implement optimizations including

In the instruction (line n) A = B + C, we have defined A and have used B and C. We say line \(n\) defines and uses these variables.

A definition \(d_1\) of variable \(v\) is killed between points \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) if every path from \(p_1\) to \(p_2\) contains another definition of \(v\); \(d_1\) is simply "visible" anymore. Otherwise, \(d_1\) has reached point \(p_2\) from \(p_1\) (i.e. a path \(p_1 \to p_2\) exists where \(d_1\) is not redefined).

An expression \(x\, \square \, y\) is available at point \(p\) if every path from the start node to \(p\) evaluates \(x\, \square \,y\), and no assignments are made to \(x\) or \(y\) after the last evaluation of \(x\, \square \,y\). Otherwise, the basic block of \(p\) kills \(x\, \square \,y\).

We define a def-use chain as a list of all uses that can be reached by a given definition of a variable. We define a use-def chain as a list of all definitions that can reach a given use of a variable.

How do we know which definitions have reached a point in the program?

Let \(S\) be a statement. We define

Then, every block in the program obeys the dataflow equations:

Dataflow equations

EquationNote: these are actually characterized over a lattice (??), where we use join and stuff. Look into this.

Notice that \(\text{in}[B]\) depends on \(\text{out}[B]\), but \(\text{out}[B]\) depends on \(\text{in}[B]\). Thus, these equations describe a dynamic system (??), so we need to apply the equations iteratively until we reach a stable point.

To find definitions, we compute \(\text{def}\) and \(\text{use}\) for each basic block (\(O(1)\)). Then, for each basic block \(B\), we initialize \(\text{in}[B]\) to \(\emptyset\) and \(\text{out}[B]=\text{def[B]}\). Then, we iterate the dataflow equations until we reach a fixed point.

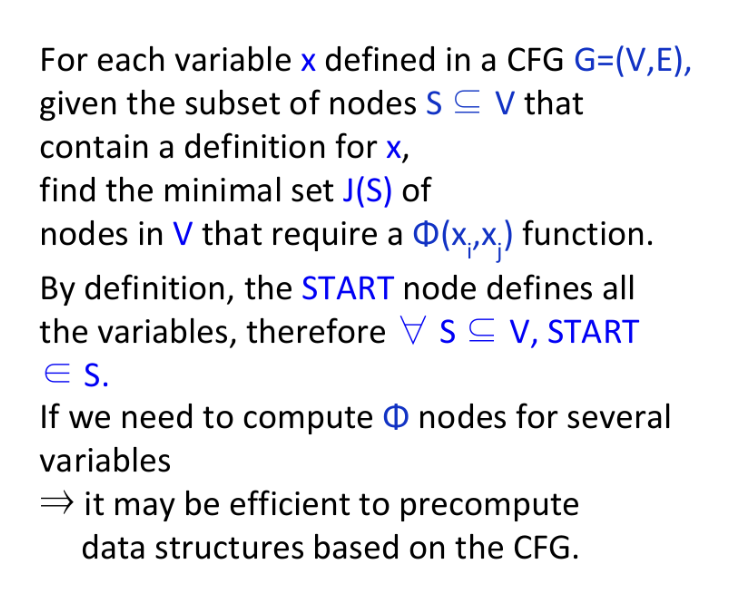

Under static single assignment form (SSA), each variable of a program is only defined once in the program's text.

Generally, SSA prevents a value from propagating (i.e. continuing to exist) in a part of the program that doesn't need it. If \(p\) definitions need to be propagated to \(q\), SSA form can reduce the edge count from \(pq\) to \(p+q\).

If a variable is assigned to more than once, we need to split each assignment into a different variable when converting to SSA form; which variable we use for a given use depends on which path we took to get to the current point (i.e. which definition we used). If the current point's block has multiple in-edges (i.e. is a control-flow path merge), this might be unknowable without actually evaluating the program.

We can define a phi function to abstract away our need to figure out which variable to use:

Note: In practice, we always define phi functions in this case, even if it turns out we don't ever use the variable. We just assume dead-code elimination will get rid of unnecessary phi functions later; this simplifies the process.

Note: since we define all the variables at the start of the program, all SSA programs start with a list of undefined variables (i.e. all the program's variables get assigned "undefined"). This still happens if the first line of the program is a definition; that becomes another split variable.

more

1991: Efficiently Computing Static Single Assignment Form and the Control Dependence Graph is published. 1990 is the start of modern SSA.

Earlier primordial ideas are present in The representation of Algorithms from 1969.

Naively, we can insert a phi function at every join point of the program (lattices?), i.e. every block that has more than one predecessor. This is very wasteful; we aren't even considering the variables themselves at all.

We only need a phi function when

Under the path convergence criterion, we insert a phi function for variable \(a\) at node \(z\) if all the below conditions are true:

Notice that, much like the dataflow equations, the PCC modifies the data it analyzes (i.e. by inserting phi functions in it). Thus, we need to apply it iteratively until we reach a fixed point.

do we need to know these??

Strategies for SSA conversion algorithms:

Additionally, many algorithms exist for computing the dominator tree.

In SSA, definitions always dominate uses: a variable is always defined before it is used, no matter where in the program it is or what path it took to get there.

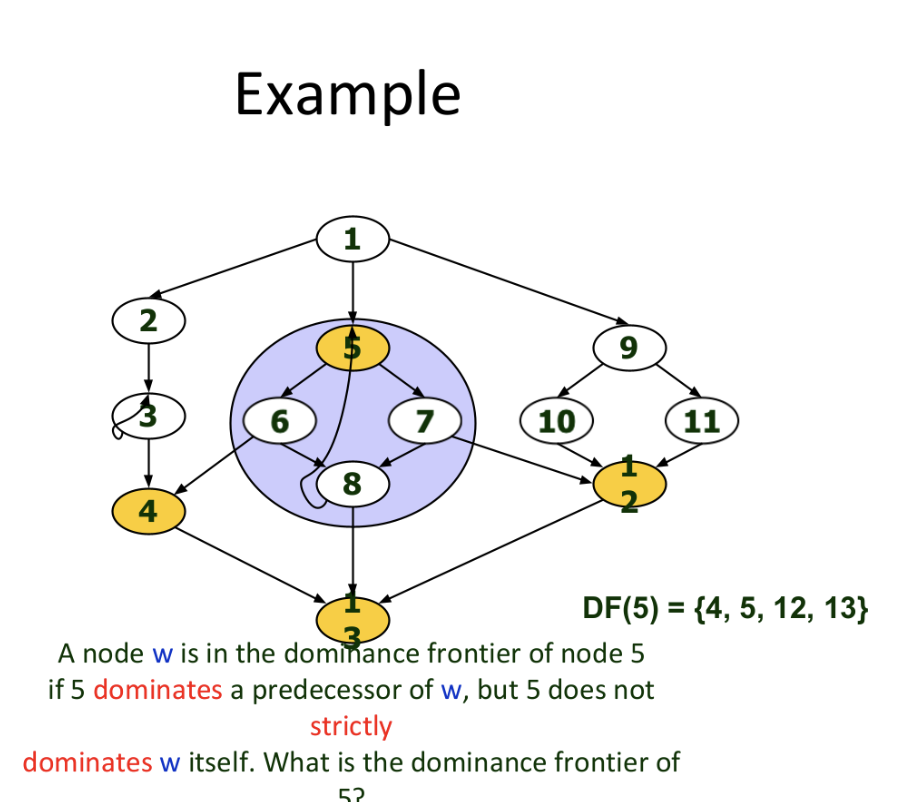

The dominance frontier \(\text{DF}[x]\) of node \(x\in V(G)\) is the set of nodes \(w\in V(G)\) such that \(x\) dominates a predecessor of \(w\), but where \(x\) does not strictly dominate \(w\) itself.

We define the dominance frontier criterion for calculating phi function placement: if node \(x\) contains a definition of variable \(a\), then any node \(z\) in the dominance frontier of \(x\) needs a phi function for \(a\).

The local dominance frontier \(\text{DF}_\text{local}[n]\) of a node \(n\) are the successors of \(n\) in the CFG that aren't strictly dominated by \(n\), i.e. are dominated by other nodes not through \(n\). Again, this implies that any node in the local dominance frontier is a join node.

passed up?

The dominance frontier is inherited from children: \(\text{DF}[n]\) consists of the local dominance frontier of \(n\) and the the union of the